This Luxury Cruise Takes You to Some of Ecuador’s Most Exciting Culinary Destinations

A new cruise along the coast of Ecuador shows off the nation's incredible Indigenous cuisine.

Rose Marie Cromwell

A course of fermented yucca bonbons with a cocoa reduction, sweet potato pickle, shrimp tail, and an Hoja Santa taco with sea bass, from the tasting menu at Iche.In the indigenous apothecary of coastal Ecuador, the palo santo tree has long held special significance. Its smoke, redolent of citrus, mint, and pine, is said to ward off evil spirits and purify the air. Tea made with its wood reportedly strengthens the immune system, and its essential oil may help fight cancer. Incense made from its resin, lately beloved by New Agey types, reputedly kindles creativity and combats negativity.

This is a lot of pressure and expectation to put on one tree.

Yet after tasting one dish at Bocavaldivia, chef Rodrigo Pacheco’s wildly imaginative, forest-shrouded restaurant outside Puerto Cayo, Ecuador, I can vouch for one more superpower in palo santo’s arsenal: the ability to inspire wonder.

Rose Marie Cromwell

Plates of pi?uela (wild pineapple) at Bocavaldivia.The night I dined at Bocavaldivia, Pacheco delivered something that shouldn’t have worked. On top of a manioc blini, a cluster of wild mushrooms, and a fat wedge of smoked Muscovy duck sat a juicy raw oyster. Somehow, each element retained its integrity while joining the others in an elegant, unlikely chorus. The catalyst: a palo-santo emulsion, which lifted the earthy ingredients, grounded the marine ones, and brought them all into delicious unity.

All of the above were native to the area. And every one was farmed or foraged within 10 miles of the restaurant, which sits a juddering, unpaved half-mile off the highway that traces Ecuador’s coast. The nearest major city, Guayaquil is a three-hour drive away.

In the indigenous apothecary of coastal Ecuador, the palo santo tree has long held special significance.

Here, amid the coastal jungle, marshy estuaries, and fertile hills of what’s now Manabí province, ancient cultures once flourished: the Valdivia, from which the restaurant takes its name; then the Chorrera; then the Bahía; the Guangala; and finally the Mante?o Huancavilca, whose chiefdoms had been under Inca rule for several decades when the Spanish colonists arrived in the early 1500s. In Manabí, their descendants have persisted in small Indigenous communities that uphold their traditions. And here, a new generation of Ecuadorans like Pacheco are now finding inspiration. “Nature is the real source of wisdom, and the people who carry it on are still here,” he said. The ancient knowledge is, as he put it, “in their soul.”

Related: How One Cruise Company Is Spotlighting Inuit Culture and Cuisine on Arctic Expedition Sailings

I had come to Manabí province to discover a destination that has remained largely under the radar for tourists, despite its natural beauty, abundant wildlife, and rich heritage. Manabí is part of Ecuador’s flyover country. Most tourists visit Quito or Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest cities, and then fly to the Galápagos Islands, more than 600 miles to the west. It’s telling that Manabí’s most famous export doesn’t even carry a local name; for centuries, people here have worn hats woven from the fibers of the native toquilla palm, but a wide-brimmed variation was popularized and branded in Panama in the mid 1800s and has been associated with that country ever since.

When Pacheco, reared in Quito and trained in Chile and France, arrived in the region a decade ago, he had little idea about his country’s own terroir. He was seeking a return to nature. With his wife, Dayra Reyes, he began rehabilitating an old, 124-acre pepper farm — the current site of Bocavaldivia. From his Indigenous neighbors, he learned more about the ecosystems — marine, rain-forest, coastal-transitional — and the bounty contained within each. In 2013, he opened the restaurant.

Rose Marie Cromwell

From left: Gabriela Estupi?an, the pastry chef at Bocavaldivia restaurant, in Puerto Cayo, Ecuador, puts the finishing touches on a dessert that uses ingredients from the surrounding forest, including passion fruit, sweet potato, cocoa, fig, and coconut; paddleboarding near the fishing village of Puerto López.Pacheco’s passion is to honor what he calls the “edible forest,” which provides everything from the bamboo cups in which he serves cocktails to the herbs and wild mushrooms that grace his dishes. He now stewards more than 86,000 acres. He has ripped out invasive species to allow native ones to flourish. He and his team have also planted a large garden. Each morning, he and a few of Bocavaldivia’s chefs go into the fields, forest, and ocean to harvest for that night’s dinner.

Manabí is one of Ecuador’s most economically disadvantaged provinces, and Pacheco recognizes that the human aspect of the ecosystem matters, too. Almost everyone on his team is Indigenous. “Just as I cultivate plants, I also cultivate talent. Most of my team haven’t finished primary school. Other places, with luck, they will become dishwashers. Here, they are sous-chefs,” he said. “I cook for a purpose. Of course I need to cover my costs, but my motivation is not money.”

“Nature is the real source of wisdom, and the people who carry it on are still here,” he said. The ancient knowledge is, as he put it, “in their soul.”

Pacheco wants diners, especially Ecuadorans, to understand the wealth contained in the country’s ancient foodways. “This is a learning experience, more than a restaurant,” he said. This would seem preachy and pretentious if the food didn’t taste so good. Especially memorable: a “bar snack” of mahi-mahi (“no tuna, because we only serve sustainably caught fish”); two slices were cured and seared, two were smoked, then all were placed on top of a mound of “earth’s caviar” — black quinoa and amaranth — flecked with smoked chili and cured egg yolk. A humita (essentially a type of Ecuadoran tamale), made with heirloom black corn and accompanied by tender sautéed squid (and its crispy fried tentacles) and a red-beet gribiche, was a wonderland of textures.

The food is unusual, even challenging. The chef’s own father struggles to understand it. “He’s more traditional,” Pacheco said, half-smiling. For instance, cheesecake is topped with eggplant poached in caramel, then served alongside coffee ice cream. “The idea comes from the garden; eggplant is neighbor to papaya, sometimes to a coffee tree. If they’re neighbors in the garden, why not on the menu?” he said. Inexplicably, it works.

Rose Marie Cromwell

Rock oyster ceviche with fresh peanuts, wild tomatoes, chicharrones, and mountain coriander at Bocavaldivia.The next afternoon, I drove an hour northeast to the port city of Manta to board the Kontiki Wayra. Once a scuba-diving vessel, the Wayra has been transformed by owner Carlos Nu?ez into a nine-cabin cruise ship. When it set sail last year, it became the only seagoing member of the Small Luxury Hotels of the World group.

The Wayra plies the waters off Manabí’s coast. To explore Manabí by sea is to regard it in historical context: centuries ago, its people sailed up and down the Pacific coast in balsa-wood rafts lashed together with rope woven from sisal, harnessing the winds with crescent-shaped sails. These were trade expeditions, not pleasure cruises. The primary unit of currency was the spondylus, a spiny oyster that can be found at depths of up to 100 feet or more. In pre-Columbian times, spondylus shells, often spiky and bright red, were used for jewelry and religious rituals. It’s said that the Inca never conquered these peoples because they so respected their ability to dive.

More Trip Ideas: These Are Some of the Best Food and Wine Experiences in Europe

Like Pacheco, Nu?ez is not from Manabí. A scion of a tuna-processing family, he fell under the area’s spell on vacations as a child. “So many people, when they think of Ecuador, they only think of the Galápagos,” he said. “There are so many other beautiful regions — and we’re trying to raise the consciousness.” Like Pacheco, Nu?ez isn’t interested in thoughtless enjoyment. He drew a contrast between “predatory tourism” and “symbiotic tourism,” rooted in “mutual respect and shared benefit.”

Nu?ez sought to integrate that cultural consciousness into the experience on board the Kontiki Wayra. The menus feature modern takes on traditional Ecuadoran dishes. His wife, Soledad, who supervised the Wayra’s interiors, commissioned Ecuadoran artisans to create blankets, furniture, and ceramics inspired by the landscape and materials of coastal Manabí. “We have so much here,” Nu?ez said. “Even Ecuadorans sometimes don’t know.”

Rose Marie Cromwell

blue-footed boobies on the Isla de la Plata.The wayra is an apt vessel for its context: comfortable but not lavish, more stalwart than sleek. The staterooms, which draw warmth from generous use of hardwood and grass cloth, are ample yet cozy. In good weather, you’ll want to head out to the open-air upper deck, perhaps to lounge with a drink from the bar or to try the inflatable waterslide that plunges you into the cobalt Pacific.

A humita (essentially a type of Ecuadoran tamale), made with heirloom black corn and accompanied by tender sautéed squid (and its crispy fried tentacles) and a red-beet gribiche, was a wonderland of textures.

About that ocean: you will feel the water — the crew doles out Dramamine liberally. But the boat’s size means that it can navigate small bays, like the one at our first stop, the Isla de la Plata. A two-square-mile rock poking out of the ocean about 20 miles off the coast, the Isla de la Plata today has no human inhabitants. But in ancient times, it served as both a site of religious ceremony and a home port for the rafts that took traders north, to what’s now Mexico, and south, to Chile.

The Isla de la Plata is sometimes called “the poor man’s Galápagos,” a damn-with-faint-praise nickname that makes locals bristle. They believe the island deserves to be recognized for its own merits, which include breathtaking 1,000-foot cliffs plunging into the ocean, rare plants including a red lily (Eucrosia stricklandii) that blooms only in October and is found almost nowhere else, and archaeological wealth — pre-Columbian artifacts and the detritus left behind by those long-ago trading expeditions.

Rose Marie Cromwell

Guests relaxing on board the Kontiki Wayra.Each day, no more than 176 visitors are allowed to visit the island, which is protected as part of Machalilla National Park. The relative dearth of human disruption has been a boon to birds. Critically endangered waved albatrosses nest here. Long-tailed mockingbirds chased each other as we hiked, escorting us along the trail. Magnificent frigatebirds, whose males inflate crimson sacs on their necks to lure mates, and red-billed tropic birds patrolled the cliffs by air.

The bird population has lately been boosted by a vigorous rat-eradication effort, which has especially helped ground-nesting species. “Ten years ago,” guide Sandra Plúa Albán said, “you would have seen rats running around everywhere, like they were squirrels.” As we crossed the scrub-covered plateau on the island’s western side, Plúa Albán suddenly stopped and pointed: “There! There!” My eyes needed a minute to adjust: perfectly camouflaged against the beiges and browns of the soil were a mother and chick — two Anthony’s nightjars, nocturnal birds that live only in a narrow arc stretching south from Ecuador into Peru.

Related: How This Stunning Island Became the Culinary Capital of the Caribbean

Unquestionably, the blue-footed boobies are the resident prima donnas. If these birds were on Instagram, they’d be the influencers — charismatic, photogenic, and unafraid. As we crested a path in the heart of the island, one booby blocked the way. She cocked her head and gazed at us, as if to ask if we were ready. Then she began to strut, every step drawing attention to her feet — so blue they looked as if they’d been dyed in the sea’s azure shallows. Farther down the path, a nesting pair watched us as we neared; then, on cue, they touched beaks, as if kissing for the cameras.

Rose Marie Cromwell

Pacheco on the path that connects Bocavaldivia to the hotel Tanusas.Our next port of call: the ramshackle fishing town of Puerto López. We moored just offshore, and inflatable dinghies delivered us onto the beach, and we boarded a minibus for Agua Blanca, a small Indigenous settlement seven miles inland.

For centuries, Agua Blanca has been known for its hot springs. In recent years, the village’s 86 families have bolstered the tourist infrastructure, spotlighting rich archaeological evidence of their heritage. A community member showed us burial urns that date back to at least 150 B.C., uncovered by a 1982 landslide. We also saw the ruins of a pre-Columbian family home, excavated by a team led by Scottish archaeologist Colin McEwan in the 1980s.

A short hike through the forest, we entered a clearing under the sprawling branches of a ficus tree. Agua Blanca’s chief shaman, Plinio Merchán, had drawn a labyrinth in the soil. At its center stood a small altar.

Related: Salvador’s Afro-Brazilian Culinary Culture Is Thriving — Here's Where to Go

Merchán handed each of us a candle and a stick of palo santo wood. He invited us to light both, deposit them on the altar, and offer silent prayers. Then he led a litany of blessings, each oriented toward one of the seven directions: east, south, west, north, sky, ground, and finally, “the point at which all the winds cross. From my heart, I salute you all,” he said, “and ask blessings on your families, your friendships, your towns, your nations.”

Nu?ez said that the invitation to participate in the ceremony had come after discussions with the community: “No outsiders have ever had this experience before.” Still, my instinct was to wonder whether we had engaged in some form of cultural voyeurism. But Merchán betrayed no such concerns, and saw no conflict between Christianity and traditional Indigenous spirituality. “I believe in one God, but that God is represented in many ways in creation.”

Rose Marie Cromwell

Walking a trail in the Pacoche Marine Wildlife Refuge.Merchán told me he felt God in the winds, the rustling leaves of the trees, and the waters of the Buenavista River, which runs through Agua Blanca. That river is now a mere trickle for much of the year. But in centuries past, his ancestors took small rafts downstream and into the ocean, moored them on the Isla de la Plata, and then boarded larger rafts for faraway destinations. They returned not just with goods but also with new traditions. He believed that his community’s rituals included elements learned from Mexico’s Indigenous peoples: “Maya? Aztec? I don’t know.”

Our visit was just a new iteration of an ancient system of cultural exchange. Given the chance to welcome — and bless — those from beyond his community, Merchán said, “I feel joy.”

Related: The Country's Best New Restaurant Is a Tribute to Indigenous Cultures Across North America

We dropped anchor in the Bahía de Caráquez, where the Chone River meets the sea, on our third day. After visiting an organic farm where we tasted multiple varieties of heirloom cacao — Manabí is a major cocoa-growing area — we drove up into the coastal hills to a restaurant and culinary center called Iche for lunch.

Iche playfully reimagines Manabí’s culinary heritage. So the spirit and flavors of a Manabita ceviche are channeled into a snapper carpaccio topped with an ice cream of peanut and leche de tigre, the citrusy marinade typically used for ceviche. Heirloom hen is prepared confit in the style of a venerable dish called seco de gallina criolla, then served over jerén de maiz, a cousin of polenta made from native corn, alongside a bright salad of amaranth, chicory, and purslane.

After lunch, we met chef Valentina Alvarez outside the restaurant, around the traditional Manabita oven — a massive wooden box, filled with dirt and clay pots, with several semispherical indentations that can be used like little firepits. “This is more than the place we cook,” she said. “It’s where we share tradition and religion and secrets.”

Rose Marie Cromwell

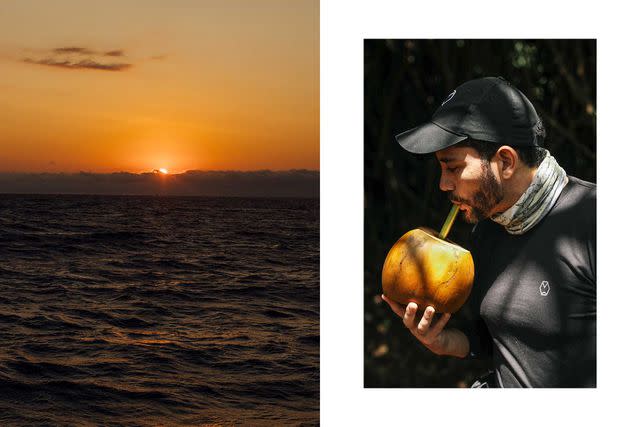

From left: Sunset off the coast of Manta, a city on Ecuador’s central coast; Rodrigo Pacheco, the chef at Bocavaldivia, samples fresh coconut water.Alvarez explained that industrial agriculture’s expansion has hurt small-scale Manabita farming. The heirloom corn she was reared on is increasingly rare. “This is a very jealous corn,” she said. “It does not like to have other varieties of corn growing nearby.” When grown in proximity to the industrial crop, it refuses to flourish; worse, cross-pollination has adulterated its genes.

Peanut is equally significant in Manabí: in the local parlance, iche, from which the restaurant takes its name, can mean “peanut” or “special food.”

Merchán told me he felt God in the winds, the rustling leaves of the trees, and the waters of the Buenavista River, which runs through Agua Blanca. That river is now a mere trickle for much of the year.

“Peanut is flavor. It is love. It is taste. To us, it is everything,” Alvarez said. “We used to have fifteen varieties here, but because of monoculture, we are losing them. We are trying to encourage the production of heirloom varieties, because diversity means sustainability.”

The dining room is just one small part of Iche’s effort. Its food lab is experimenting with ways to preserve and unlock the value of heirloom crops — extracting oils, dehydrating fruits, fermenting produce, making vinegars, redistilling spirits. Our meal was largely prepared by the students in a seven-month culinary training program designed to teach both modern cooking skills and deeper knowledge of Indigenous foodways. “We give our students tools and techniques to innovate and create sustainable food,” Iche cofounder Adriana Arellano said. “They become ambassadors for the new Manabita cuisine. They can take it another step — and maybe even to the world.”

Rose Marie Cromwell

Playing in the waves at Murciélago Beach, in Manta.On our last stop in Manabí, we docked in the village of San Mateo and drove 15 minutes to the Pacoche Marine Wildlife Refuge. Barely 50 yards down a forest path, guide Carlos Alvia began a rapid-fire narration of the botaniscape: Pi?uela, good both for fencing and for eating, “but too much and it’s a laxative.” Ortiga (nettle), “used to help circulation as well as alopecia, if you mix it with aloe vera for shampoo.” Malanga, whose broad leaves serve as a water collector (“look for it for survival”) and whose root is used as food (“feels almost like eating a potato, and it’s rich in vitamin D”).

Alvia illuminated things in the forest that escaped our sight. That cuplike construction of small branches and spiderweb, tucked amid dense bamboo? “The nest of an Amazilia hummingbird,” he said. Adjacent to the path, some leaves were tamped down, some brush pushed aside: a corridor created and used by animals, “maybe armadillo, or pig, or ocelot.”

As we descended into a valley and humidity thickened the air, Alvia sprinted forward, gently extended a hand into the leaf litter, and then lifted it up to present a frog smaller than a fingernail: a machalilla. On its back, the frog carried what looked like a spoonful of caviar — the eggs of the next generation.

When Alvia was a kid, this was communal land. Nobody owned it. Everybody used it — to harvest wood, to hunt, to forage for mushrooms. Only when he became a guide did Alvia begin to see all that the forest held. It is habitat and apothecary, pantry and toolshed.

Now that the Pacoche Refuge, like the rest of Manabí, is drawing growing numbers of tourists, he hopes it will be honored for generations to come. “When you know a place, you can protect it,” he said. “And I love this place, so I want it to be shared with everyone.”

Ecuador, from Farm to Coast

Where to Stay

Tanusas: Nearly every room at Tanusas — the boutique hotel in Puerto Cayo adjacent to chef Rodrigo Pacheco’s restaurant, Bocavaldivia — features sweeping views of the beach and Pacific Ocean.

Where to Eat

Bocavaldivia: There is no fixed menu at Bocavaldivia, where chef Rodrigo Pacheco and his team cook multicourse tasting meals honoring Ecuador’s culinary heritage.

Iche: Both a culinary training center and a restaurant that celebrates the food of Manabí province, Iche puts an innovative spin on ancient ingredients and techniques. The bar serves cocktails made from spirits redistilled on site.

What to Do

Kontiki Expeditions: The nine-cabin Kontiki Wayra embarks from the port of Manta, about three hours’ drive northwest of Ecuador’s largest city, Guayaquil.

A version of this story first appeared in the February 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Gifts of Land and Sea."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.