Mary McFadden Recalls Being the CFDA’s First Female President

As the first of three women to have been president of the Council of Fashion Designers of America in its 60-year history, Mary McFadden remembered that role with fondness and candor.

In 1982, McFadden became the first female president thanks to the publicist Eleanor Lambert, who represented the designer’s business as well as other leading American ones at that time. Asked about how much of a weighing factor that professional connection was, McFadden said with a laugh, “Of course, of course ?— that’s why I got the job.”

More from WWD

The prospect of how beneficial taking on the role of president would be to McFadden’s business was how Lambert presented the proposition. “That’s correct and it was. It gave me more visibility,” McFadden said.

Lambert, who helped found the organization, was also a great friend to McFadden, who always admired the publicist. Unfailingly perfectly put together, Lambert worked tirelessly for her clients.

Along with being a designer, the five-times married McFadden is a collector and inveterate traveler who has ventured to the far corners of the globe. When she opened her company in 1976 in New York City, the intricate designs drew inspiration from the art and cultures she experienced in China, Africa, Greece, South America and other regions. A three-time Coty award winner in the late ’70s, McFadden patented the Marii pleated fabric, introduced home furnishings, a more affordable diffusion apparel line and knitwear, among other categories. Dubbed “the fashion archeologist,” McFadden explored ancient civilizations and amassed a covetable collection of textiles that includes purchases she made in markets in Malawi, Harar, Addis Ababa and other locales.

As for how her world travels impacted her yearlong run as the CFDA’s leader, McFadden said, “I suppose all of your experiences do change your perspective.”

Televising New York fashion shows and hosting them under one roof were two of the forward-thinking ideas that she proposed. Although that didn’t happen under her reign, McFadden said, “I don’t think people were nonreceptive to it. I think most people wanted as much publicity as they could get.”

Interested in the interplay of textiles, the designer created embroidered chiffons, sumptuous silks, precise vertical pleating, stitch beaded cuffs and collars, draped velvets, sculptural jewelry, braided belts and other accents that suited different body shapes. With her alabaster complexion, striking bob and lithesome physique, McFadden was and remains her own ideal model. McFadden started her career in fashion as director of public relations at Dior New York. After leaving there in 1964 and before she started freelancing in apparel and jewelry design, McFadden freelanced for a range of magazines in South Africa in the mid- to late-’60s after moving there with her first husband Phillip Harari in 1965. McFadden went on to freelance for French Vogue in 1968 and to serve as special projects editor at American Vogue. McFadden’s presence in the fashion industry can still be seen at 240 West 35th Street, which, as the etching above the entrance indicates, is known as the Mary McFadden Building.

McFadden’s stewardship also bolstered awareness about other American designers. Looking back, McFadden said that was what she was most proud of. “We got American fashion into an international situation by having more organized fashion shows and the Coty awards,” she said.

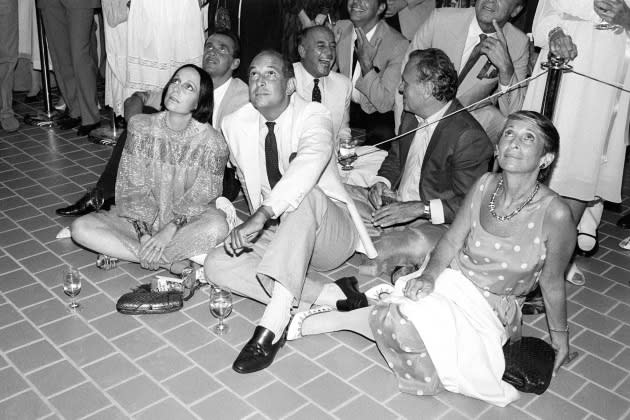

During the ’80s, there was a sense of camaraderie and liveliness within the CFDA that created social bonds that were as strong as the professional ones for some members. “Some fashion people wanted structure around them,” McFadden said.

Undeniably, designers also upped the era’s glamour just by how they dressed. That came naturally though for most, according to McFadden, who believes that the notion of having to dress that way as a job requirement was not something that ever occurred to the designers of that time. “It was all a matter of doing well in the meetings, projecting our image and moving [American fashion] forward.”

“A lot of publicity sure helped” in achieving that, McFadden said. That approach varies from today. “Everyone is pretty established now through social media.”

McFadden succeeded Bill Blass and preceded Perry Ellis as the CFDA president. Heading up the organization wasn’t very taxing or time-consuming, since the group was small, unlike today. Meetings typically lasted for an hour and McFadden held them in different designers’ offices, free from any contentiousness or a lot of laughter. Rather than run through minutes or an itemized list of issues that needed to be discussed, the CFDA meetings were totally untraditional because McFadden was running them, she said, laughing. “There were no people hanging around taking notes.”

In June 1982, McFadden had suggested showing the Seventh Avenue collections at the Seventh Regiment Armory on East 66th Street or at two unused West Side piers. She also proposed staging a TV spectacular titled “The Great Discards” to finance it. The name struck Blass as “rather odd” and “anything with a negative in the title is not good.” McFadden saw it as a wink at designs that never made it from the runway to the production line. Considering the prospect of staging the Seventh Avenue collections under one roof, the CFDA first soundly wanted to evaluate the potential costs. Ellis was more receptive to that idea, allowing that it had really worked in Paris and Milan.

Synergy was another concept that McFadden embraced earlier than most. In 1983, McFadden organized a CFDA cocktail party at the St. Regis that was sponsored by the organization and Ideacomo that featured a parade of a single looks from 50 different designers on a model or a celebrity. The event was slated for the night after her own show, which was inspired by “Napoleon at the gates of New York.” The cocktail party was meant as a thank you to Ideacomo for its sponsorship of the CFDA.

A few years prior to her presidency, McFadden literally helped wave the flag for the American fashion industry. As chairman of the CFDA banner committee in February 1979, McFadden and others asked designers to submit ideas for three “New York, New York — Fashion City” banners that were later flown above Seventh Avenue. The heads of Parsons School of Design, the Fashion Institute of Technology and Traphagen chose Blass’ inverted triangle designs above the 29 other contenders. But he was asked to pep up the neutral shades that he originally submitted. Mayor Ed Koch was among those on the guest list at a celebratory unveiling event at McFadden’s factory.

That spring, Calvin Klein declined a menswear Coty award nomination and a womenswear designer citation by sending a telegram to Lambert. Reached at that time in a New Mexico desert by WWD, Klein said it was absolutely a personal reason, but he declined to elaborate. That summer McFadden served as vice president of the CFDA along with fellow vice presidents Oscar de la Renta, Herbert Kasper, Stan Herman, Mollie Parnis, Jose Martin and Charles Suppon. Blass had been elected CFDA president, succeeding Kasper and the group’s board increased its members from 12 to 14.

Even though in January 1982 a “Dr. Zhivago”-worthy blizzard descended on New York City streets on the evening of the CFDA awards dinner at the New York Public Library, the fashion flakes persevered, according to WWD’s coverage. Once indoors, everyone was welcomed by Sergeant Major Mary McFadden, “who had the evening very efficiently in hand,” WWD reported, right down to the Mary McFadden “Crystal Dream” bedsheets that were used as tablecloths for the Glorious Foods dinner spread, and the gilded squash and cranberry centerpieces. “Major Mary” also mandated that only the legal wives and husbands of the CFDA members were allowed in on the same ticket. “So we’re quite heavy on the men to say the least,” she explained at the event.

Although McFadden remains a CFDA member, she is not too involved with the organization, having shuttered her business for good in the ’90s. “I’m not really longing to sell anymore. Therefore, the CFDA is less important for me. Of course, I’m still a member. I think the organization today is great,” citing the size of the organization, and its educational and mentoring opportunities as some of the benefits.

Asked if there was anything she misses about the fashion industry, she said, “Everything — of course — it was a lot of fun. I miss the shows particularly. Not just the anticipation and how the crowd reacted, but the whole thing.”

Right now, though, the designer is pretty retired, which is a nice change of pace after so many years of working. She does not currently have a favorite designer, having not studied the situation. All in all, there is nothing that she wishes that she had had the time to get to. “I can’t see anything on the horizon that I would have done differently.”

McFadden did offer some insight to those who have never worked in fashion about what they might learn about it: “Maybe they would enjoy dressing up more.”

Acknowledging how relaxed most people now dress, she said, “Well, that could change tomorrow.”

Best of WWD

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

RSVP for "A Matter of Style", a Fairchild Archive exhibition September 9-10 in New York City.