‘You mean I’m gonna stay this colour?’ The deeply stupid genius of Steve Martin’s The Jerk

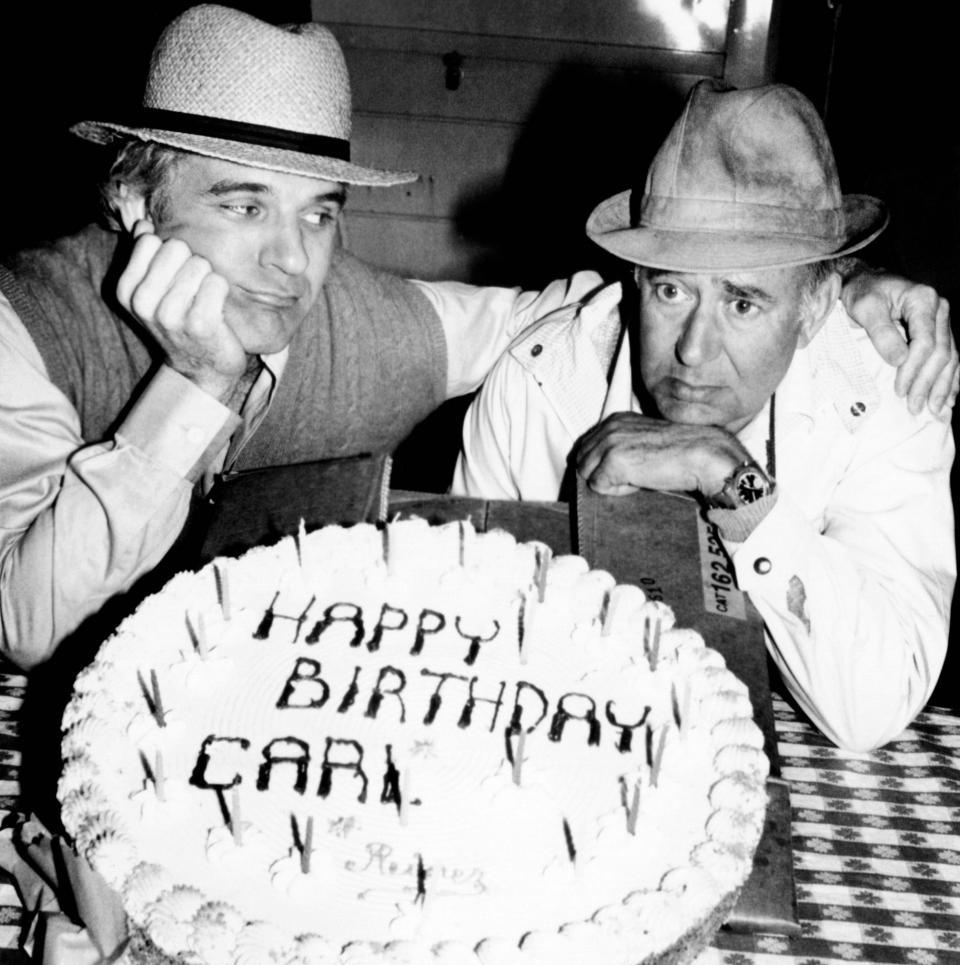

In July 1979, five months before the release of The Jerk, Steve Martin and director Carl Reiner put on a glitzy premiere gala. Not for the film, but the trailer.

Held at the Village Theatre in Westwood, Los Angeles, it was – as Martin and Reiner described – an “unprecedented event”: swirling spotlights, a fanfare-blaring marching band, and 500-plus guests, some of whom lined the red carpet wearing rabbit ears and arrows through the head – trademark props from Martin’s mania-inducing stand-up routines. Newspapers listed the event – the joke was seemingly lost down the newswire – as taking place between 8pm and 8.02pm. No one would be seated after the first six seconds. Dress was optional. “But they preferred it.”

Steve Martin, arriving in a limousine and wearing black tie, talked to reporters. “We were tired of phony Hollywood premiere parties,” he said. “We decided we were going to have a genuine premiere with genuine people.” Martin explained that the trailer for The Jerk was rated “ugh” and that production had been an all-round success. “We were able to bring it in under budget and under schedule,” he confirmed. “I believe we saved $94.” Inside the theatre, Martin made a speech and wept. “I can honestly say these are the most exciting two minutes of my life.”

This swipe at Hollywood self-importance was the kind of ostentatious stupidity befitting Martin’s character in The Jerk, Navin R Johnson. He’s less an actual jerk, more a nincompoop – a self-unaware na?f. Raised with a black family in Mississippi, Navin doesn’t even realise he’s adopted. “You mean I’m gonna stay this colour?!” Navin cries when he learns the truth from his mother. Michael Elias, who co-wrote the film with Steve Martin and Carl Gottlieb, still chuckles at the line now. “It’s one of the great lines in comedy history,” says Elias.

The Jerk was the moment in Martin’s career that effectively bridges the two halves of the new Apple TV+ documentary, STEVE! (martin) A Documentary In 2 Pieces, directed by Morgan Neville.

The first half of STEVE! tells the story of his rise to stand-up comedy mega-stardom – a stadium-packing cultural phenomenon. “He was getting 10,000 people to come to his concerts,” says Elias, who wrote material for Martin’s live act and witnessed it first-hand. “He was like a rock ‘n’ roll comedian. He was the first one.” The second half of STEVE! is about Martin’s movie career and the effect it had on his personal life.

The Jerk was made at a time when Martin felt that he could no longer be truly creative in stand-up – that his immense popularity was “a fad” and would soon be over – and it convinced him to leave stand-up for movie stardom. He had found his special purpose. But that underplays what, more than anything, The Jerk actually is: one of the funniest comedy films ever produced.

When Steve Martin began writing The Jerk – first with Carl Gottlieb – there wasn’t much of an idea beyond it just being funny. Gottlieb (who also wrote the screenplay for Jaws) remembered them sitting there for days on end, just staring at a blank page. Inspiration eventually came from a line in Martin’s stand-up routine that always got a laugh: “I was born a poor black child.” It’s an idea that’s lost none of its ridiculousness in 45 years. “There was no whiter man than Steve,” Carl Reiner told Nick de Semlyen, author of Wild and Crazy Guys, about 1980s comedy stars. “He even had white hair.”

In the eventual film, Navin’s calling comes when he finally finds his rhythm. Not clumsily finger-snapping to the blues – “There’s something about those songs, they depress me!” – but when he hears some painfully white elevator-style music on the wireless. “It speaks to me!” he declares. “If this is out there, think how much more is out there!” Navin ventures out into the world to make something of himself, but not before the family teach him a few life lessons, including “don’t trust whitey” and how to know the difference between s--- and Shinola.

The Jerk was initially developed at Paramount and called Easy Money. Martin told Reiner that he thought the title needed to be “something short, yet have the feeling of an epic tale. Like Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot but not that. Like The Jerk.”

Paramount dropped the film after a management changeover and Universal picked it up instead. By now, Gottlieb had moved onto a different project, so Martin asked Michael Elias to work with him on rewrites. Elias travelled to Aspen, where Martin lived at the time. They skied by day and wrote the script at night.

Elias is now a novelist. His most recent book, You Can Go Home Now, is a thriller that “takes on the anti-abortion terrorist movement”, says the writer.

Looking back at The Jerk, Elias credits the piecemeal collaboration between himself, Martin, Gottlieb, and Carl Reiner – as well as the hands-off producers, David V Picker and William E McEuen. There was no studio interference, no notes, no compromises. “We did not know we were making a comedy classic,” says Elias. “We approached it as ‘We’re making a movie!’ Only we felt free to do whatever we wanted. I don’t know if you can do that anymore – make that kind of movie where you say, ‘We’re not listening to anybody.’ Maybe that’s why it’s survived so well.”

Martin later admitted that when writing The Jerk, he didn’t yet know the rules of screenwriting. Like Navin, he was na?ve to the new world he was inhabiting. “Its vision was laughs, jokes,” said Martin on the So Many Steves podcast. “But it wasn’t the vision of a movie, it was the vision of something else, of just putting comedy on screen.”

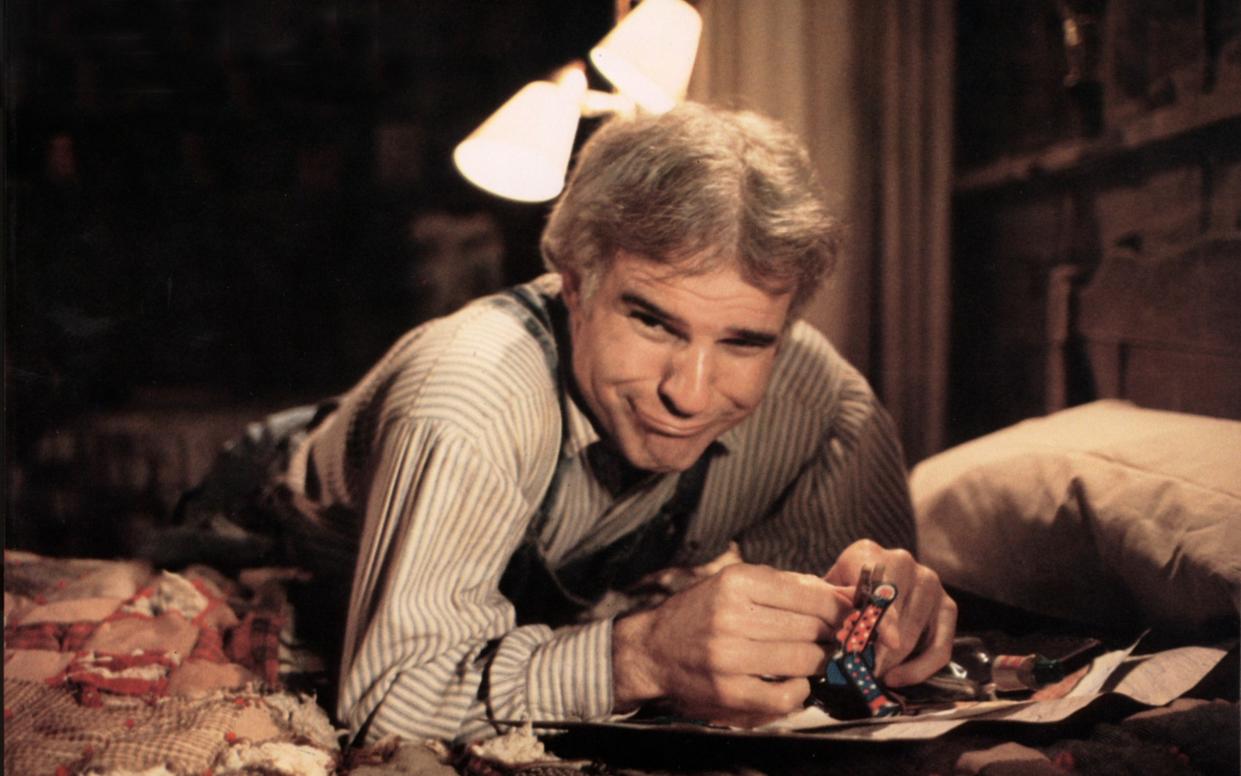

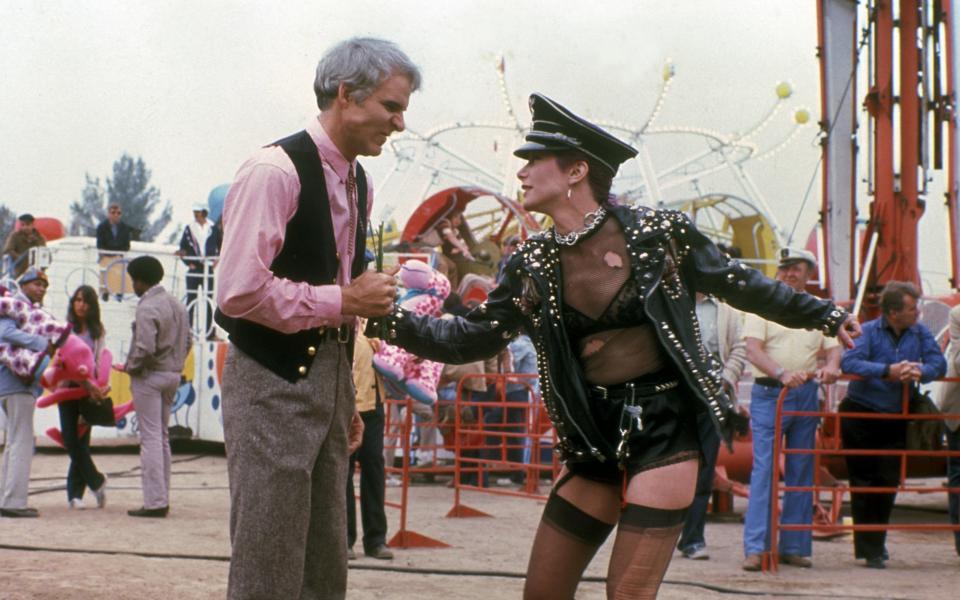

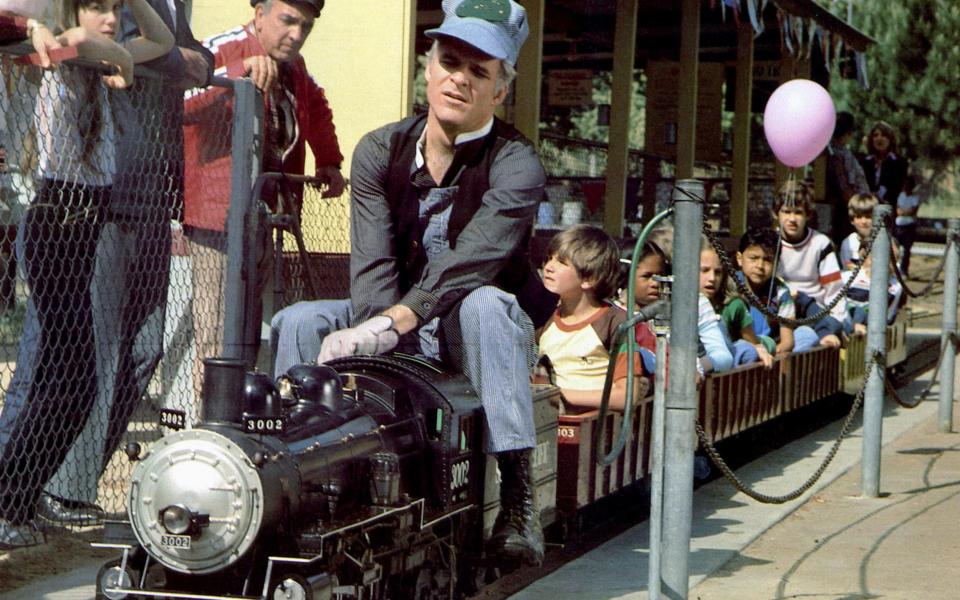

Indeed, rather than follow a standardised movie structure, The Jerk plays like a odyssey of skit-like life chapters, steered by a series of odd jobs: gas station attendant, carnival weight guesser, miniature train driver, unwitting inventor. Meanwhile he loses his virginity to a hardened stuntwoman who tattoos his name on her backside (“I’ll bet more people see that than the phonebook!”) and falls in love with the cutesy-voiced, doll-faced Marie, played by Martin’s then-girlfriend, Bernadette Peters. (One job that didn’t make the final script was “buffalo counter” – standing on a street in Beverly Hills and counting any buffalo that pass by. After a few days, a buffalo would finally appear. “One,” he would say, noting it on his clipboard.)

Navin’s ambitions are modest. Just getting his name in the phone book is enough. “Millions of people look at this book every day! This is the kind of spontaneous publicity – your name in print – that makes people!” He becomes an overnight millionaire when he invents the Opti-Grab – a little handle that goes on the bridge of spectacles – but loses his fortune when the Opti-Grab starts turning people cross-eyed. For Elias, The Jerk was in the grand American tradition of rags to riches stories (then back to rags and sort-of riches again in Navin’s case).

As detailed in the STEVE! documentaries, Martin’s stand-up had marked a shift in comedic philosophy that rubbed against the grain of the cultural moment. Other comedians in post-Vietnam, post-Watergate America were doing politics and satire, but Martin’s act was an expression of rampant, force-of-nature, full-throttle silliness – talking about Bananaland and doing the happy feet jiggle, while wearing a rubber nose and balloon hat. A wild and crazy guy, as he would put it.

In the first part of STEVE!, he explains that his initial approach to stand-up was to remove to the formalities of comedy – the unspoken pact in which comics would build the tension of a joke and release that tension with a punchline, signifying that it was time to laugh. “What if I created tension and never released it?” he says about crafting his act. “I was after that quality that is indefinable. Where you said, ‘I don’t know why that was funny, but it was.’”

That’s also true of The Jerk, which lampoons the form with a sustained comedy tension. Laughs are perpetual, coming in all forms: physical slapstick, abstract asides, conceptual buffoonery, silly songs, one-liners, good old-fashioned swearing, and straight-up, bullet-proof gags. “S---, Shinola,” says Navin as he learns the difference – then strolls through a steaming pile of the former. Other personal favourites: his faithful companion dog, S--- Head; the cat juggling routine; and the pendulous defences of Iron Balls McGinty (actually played by Gottlieb).

Laughs hang in the ether of almost every second of The Jerk’s runtime – the sensibility of Martin’s stand-up made into its own reality. “The movie represented my small act’s ultimate expression,” Martin wrote in his memoir, Born Standing Up. Unlike, say, Airplane – one of the few comedies that stands up against The Jerk laugh-for-laugh – it’s not about ridiculousness played straight. Martin plays it all ridiculously. In The Jerk, the rest of the world is his straight man.

Many of Martin’s favourite gags in The Jerk came from bantering with Carl Reiner as they carpooled back and forth from the studio. Martin, when introducing the film for the American Film Institute in 2008, recalled how he and Reiner laughed for the entire journey over his favourite joke. When Navin is hitchhiking, a truck driver offers him a lift. “St Louis?” asks the driver. “No,” Navin replies. “Navin Johnson.”

Reiner also enjoyed getting Martin to come up with on-the-hoof material. After every take, Reiner would ask, “You got anything else Steve? Anything else cooking in your head?”

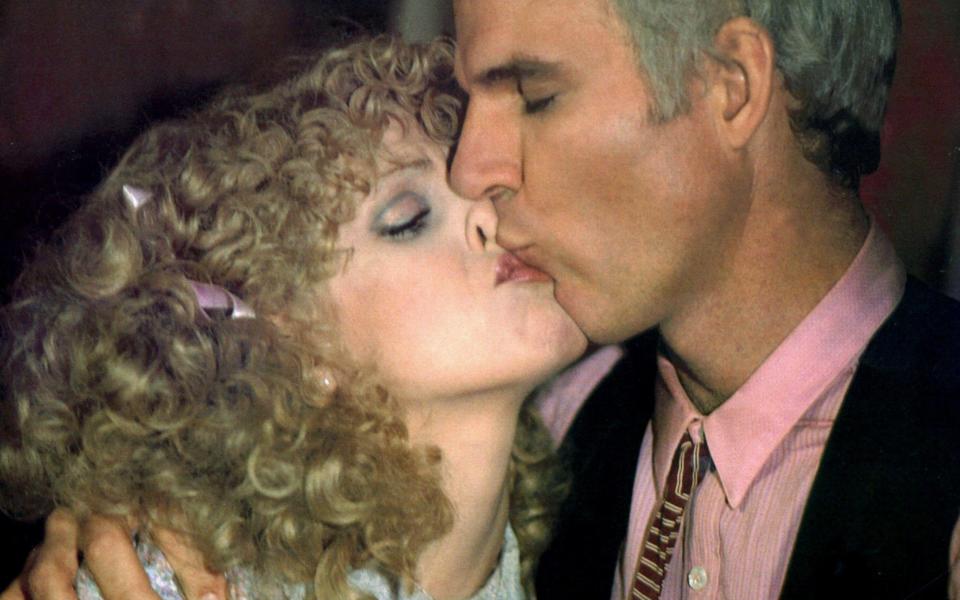

Reiner, a veteran comedian, became a mentor of sorts for Martin and frequent collaborator in Martin’s early film career. He also directed Martin in Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, The Man with Two Brains, and All of Me. In The Jerk, when Navin and Marie are about to kiss for the first time, it was Reiner who quietly suggested that instead of kissing, Martin should surprise Bernadette Peters by licking her face. “What’s amazing is that you can see that she’s about to break and doesn’t,” says Michael Elias. “Bernadette Peters is genius in that movie. Really f------ brilliant.”

Another of Martin’s favourite moments is more sweet than funny: a moonlit rendition of Tonight You Belong to Me as they stroll along the beach, with Navin on the ukulele and Marie on the cornet. (It’s not without laughs though. Navin fantasises about climbing into Marie’s cornet, clambering through the valves, and kissing her lips. “Why didn’t you?” she asks him. “I didn’t want to get spit on me,” he says.) Martin recalled waiting for the scene to play at a preview screening, hoping that the audience would love it. Instead, they filed out of the auditorium to buy popcorn. Still, it has a touch of the romance and sentimentality that became part of Martin’s later films.

It says something about The Jerk too, which – like Navin Johnson himself – is completely pure-hearted and uncynical. That’s perhaps why The Jerk gets away with material that would usually be cancel culture fodder – particularly Navin growing up a poor black child. Interviewed in 2019, Carl Gottlieb admitted The Jerk has “a lot of very innocent, but racist clichés” though he stressed The Jerk was “never ill-intentioned”. Michael Elias recalls being in a cab and telling the driver, who was black, about The Jerk. “I said it’s about this guy who’s adopted by a black family and thinks he’s black and he’s grown up black,” says Elias. “The guy said, ‘Woah, that’s heavy!’”

In another scene, Navin is targeted by a crazed gunman, played by the late M Emmet Walsh. A gag about an active shooter should feel uncomfortable in 2024 – when the idea is more than a whacky sketch – but it’s so ludicrous it works. The gunman picks Navin’s name out of the phonebook at random and takes aim, leading to an oblivious Navin yelling arguably the film’s funniest line (“He hates these cans!”). The shooter reappears later and explains the attempted murder. “That was the old me… I had a bad marriage and I just gave up smoking.”

Some of The Jerk’s best material comes when Navin becomes pompously, filthily rich from inventing the Opti-Grab. The newly-sophisticated Navin piles his neck with gold chains, drinks Chateau Lafite-Rothschild straight from the water cooler, and eats in posh restaurants – though he’s appalled when he orders the escargots and finds snails on the plate. “You would think in a fancy restaurant like this, at these prices, you could keep the snails off the food!”

Navin’s Beverly Hills mansion is a bastion of bad taste, with explicit artworks, a rotating bed with pink chiffon and zebra stripes, a clam-shaped bathtub, an all-red billiard room with a stuffed camel, and a dedicated disco room. Incredibly, the 38-room mansion was real. “The house was insane,” says Elias. “There really was a stuffed camel.”

Located on Sunset Boulevard, it belonged to a Saudi Arabian sheik, Mohammed Al-Fassi, who was worth a reported $6 billion. Al-Fassi outraged his neighbours with his gaudy décor. He painted the mansion a colour described as “rotting lime” and painted the statues (including their genitals – and adding fuzzy pubic hair) on the front veranda. The studio rented the house for $50,000 a week, which saved the trouble of decorating a house from scratch.

The Jerk’s best remembered scene comes after Navin has lost his fortune to cross-eyed glasses-wearers (Carl Reiner cameos as himself – one of the many people turned cross-eyed by the Opti-Grab). In a gag cribbed from Martin’s stand-up, Navin walks out of his mansion a broken man, declaring that he doesn’t need anything. Except the ashtray, the remote control, a paddle-ball game, some matches, the lamp, and a chair. “That’s all I need!”

There’s an intelligence beneath the stupidity – even beyond the film. When Martin and Reiner hosted their trailer premiere, the joke didn’t stop with the daft fanfare. The smartest part was not even screening the real trailer, but a phony “for theatre owners only” trailer in which Martin talked directly to camera, promising the cinema bosses that The Jerk would be a real “money-maker” and they’d all be in the Bahamas before the public realised they’d been swindled. He’d paid off the critics to ensure box office, included blue language to keep audiences happy, and stuck a boring bit in the middle so that viewers (“a bunch of idiots”) would buy more popcorn. “You’re welcome,” Martin said, grinning. “A gift from Steve.”

There was one person who attended the trailer shenanigans and who wasn’t impressed (or so he pretended): Bill Murray. Murray had a small cameo in The Jerk, playing an interior decorator, but the part was cut – a point that Murray raised when he jokingly reviewed the film on Saturday Night Live. “The movie is a dog. There’s something missing.” Murray’s gag wasn’t the only bad review. In his memoir, Martin recalled The Jerk getting “one lone good review from a small paper in Florida” but “dismissive and sadistic reviews from the rest of the country”. Even Martin’s own father dismissed his son’s performance after a preview screening, “Well, he’s no Charlie Chaplin,” Martin’s father told a friend. The Jerk, however, released in December 1979, was a smash hit, making $73.7 million.

Forty-five years on, The Jerk is still joyously unusual – both a comedy classic and off-the-beaten-track. A film that the most serious comedy fans seem to know and appreciate.

Michael Elias puts its success down to Martin’s time in stand-up. Not just for the material and comedy sensibility borrowed from his act, but the mindset of needing to make people laugh from the off. “If you don’t go out and make people laugh, you’ve bombed,” says Elias. “For Steve, as a comedian, it was a matter of life or death. He made sure – we all did – to take that responsibility. To make sure it was funny.”