Meet the researchers who want to reverse covenants that once kept people of color from living in Whitefish Bay

In 1993, Kathy Wurzer and her husband were looking for a fixer-upper – a house the couple could put their mark on.

They found it in a quaint, tree-lined subdivision in Whitefish Bay.

She and her husband, Ron, 65, moved in and years later adopted their daughter, Emma. Had they been house hunting six decades earlier, the Wurzers would have been barred from living in the north shore suburb.

The Wurzers' home was part of a subdivision once known as Bay Ridge. Homes in Whitefish Bay had racially restrictive covenants that forbade anyone other Caucasians from buying or even occupying a home there. The Wurzers are white. Emma, now 22, is Black.

“I sat there, and I cried,” said Wurzer, 63. “I have a daughter who is African American, and she wouldn’t have been allowed to live in this community.”

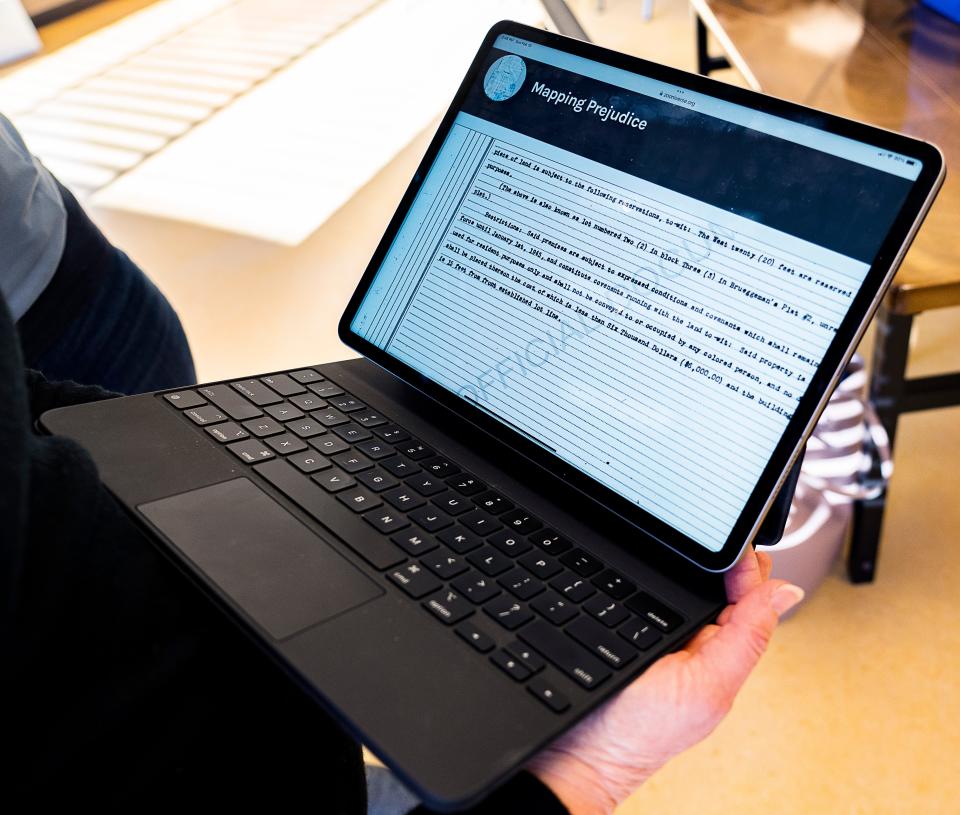

Wurzer learned of her subdivision’s past three years ago when her friend, Anne O’Connor, showed her a copy of a deed that contained a racially restrictive covenant. Wurzer had heard about these covenants from a presentation made by Milwaukee historian Reggie Jackson, but never imagined she would come face to face with it.

“I hadn’t seen it in that blatant language…,” said Wurzer, who along with O’Connor and Jenn Koop Olsta co-founded Bay Bridge, a Whitefish Bay–based organization missioned to raise awareness about racial and cultural bias.

“It was like a punch in the stomach realizing that was the community that I was living in,” she said.

The restrictions had a long-lasting effect on a city's make up

The women are leading an effort to get all Milwaukee County municipalities, especially those in the North Shore suburbs, to pass the Resolution to Repudiate Discriminatory Covenants that denounces these restrictions. Many of these communities’ racial make-up can be attributed to these restrictive covenants.

Racially restrictive covenants played a pivotal role in shaping the racial geography of not only the suburbs, but also of the city of Milwaukee. They forbade the sale of land or homes to Blacks and people of other ethnicities to keep certain areas exclusively white.

“I think until we acknowledge our horrific horrific history in this country of racism, we can’t really move forward,” Wurzer said.

Although these covenants were crafted decades ago and are now illegal, people should feel compelled to try to right this wrong, O’Connor said.

“We can’t just sit around and say, ‘That’s terrible.’ We have to do something,” she said. “To actually see that language, see the intentionality that went into it, that’s why we have to be equally intentional about undoing it.”

The restrictive covenant found in Bay Ridge isn't an anomaly. O’Connor has found dozens more in Whitefish Bay. She has been “transcribing” digitalized copies of Milwaukee County property deeds looking for these covenants as part of the Mapping Racism and Resistance in Milwaukee County.

Spearheaded by two University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee professors, Anne Bonds and Derek Handley, the project aims to map and document these covenants in Milwaukee County with help from the public.

How widespread were the covenants?

O’Connor has looked at more than 450 documents since last fall on the project's online database. Of them, 90% have restrictive covenants. She was even surprised to learn these covenants extended even in death.

“To learn that even cemeteries were segregated really exemplifies what some people were thinking at that time,” O’Connor said. “People went to great lengths to put it in a cemetery.”

The effort came after Bay Bridge, with Christ Church Episcopal and dozens of other community partners, hosted a community discussion last April about restrictive covenants with Bonds and Handley. The group based their resolutions on similar efforts in other states such as Minnesota and Washington state. The language was adopted to make it specific to Milwaukee County but adaptable for other municipalities to use as a template.

They are drafting a toolkit to help organizations encourage local governments to adopt the resolution or look at other ways to address fair and equitable housing. The toolkits provide background on restrictive covenants, information on the Mapping Prejudice project and how to identify elected officials including trustees or supervisors.

Last summer, Whitefish Bay, Shorewood and Greendale each passed the resolution repudiating these covenants. Several Milwaukee County supervisors attended that April discussion and passed their own resolution in June.

The group is now working on Fox Point, Glendale and Bayside.

Eva Hagenhofer, a member of the social justice committee of the Congregation Sinai of Fox Point, is also part of the effort. She knows more affluent suburbs like Fox Point might be harder to convince.

“Every community has to deal with their own histories and their own political dynamics,” Hagenhofer said.

She hopes people see this initiative as a teachable moment. It’s an opportunity to have tough conversations about integrating neighborhoods, zoning issues, building affordable apartments “and all the other things that stand in our way to have equitable communities,” she said.

“History matters,” Hagenhofer said. “If you don’t understand how we legally and otherwise manipulated the system in the past, then the conclusion you have about why we are a white suburb goes in a really bad direction.”

Cities are taking action against their own restrictions

Many, she said, will assume people of color don’t want to live here or want to live with their own people.

“We need to know why things are the way they are,” Hagenhofer said. “Hopefully people will be indignant enough that they will want to take the next step.”

Bonds, the UWM professor, called it impressive that communities have taken up the challenge of denouncing and repudiating the covenants, even though doing so wasn't the project’s goal.

“When we started this project, the goal was to document all of the racially restrictive covenants, to understand more about their ongoing impacts, and to foster community understanding of the histories of racial covenants in Milwaukee County,” said Bonds, associate professor and associate chair of the university’s department of geography.

Several proposals have been made to remove such covenants, including one recently by Wauwatosa. The Wauwatosa Common Council proposed a state law that would help remove these restrictive covenants from deeds across Wisconsin.

Bonds understands a desire exists with some residents to get rid of these covenants, but said simply removing them could hinder historical research.

“If we were to strike them entirely, that would limit our ability to understand how much land they covered, what were their legacies, their impacts of property values or how might they have shaped patterns of racial and class segregation,” she said.

“It's just a concern that history is not erased by the efforts for residents to have these covenants removed,” Bonds added.

La Risa Lynch is a community affairs reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Email her at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: An effort is underway to reverse restrictive covenants in Milwaukee County