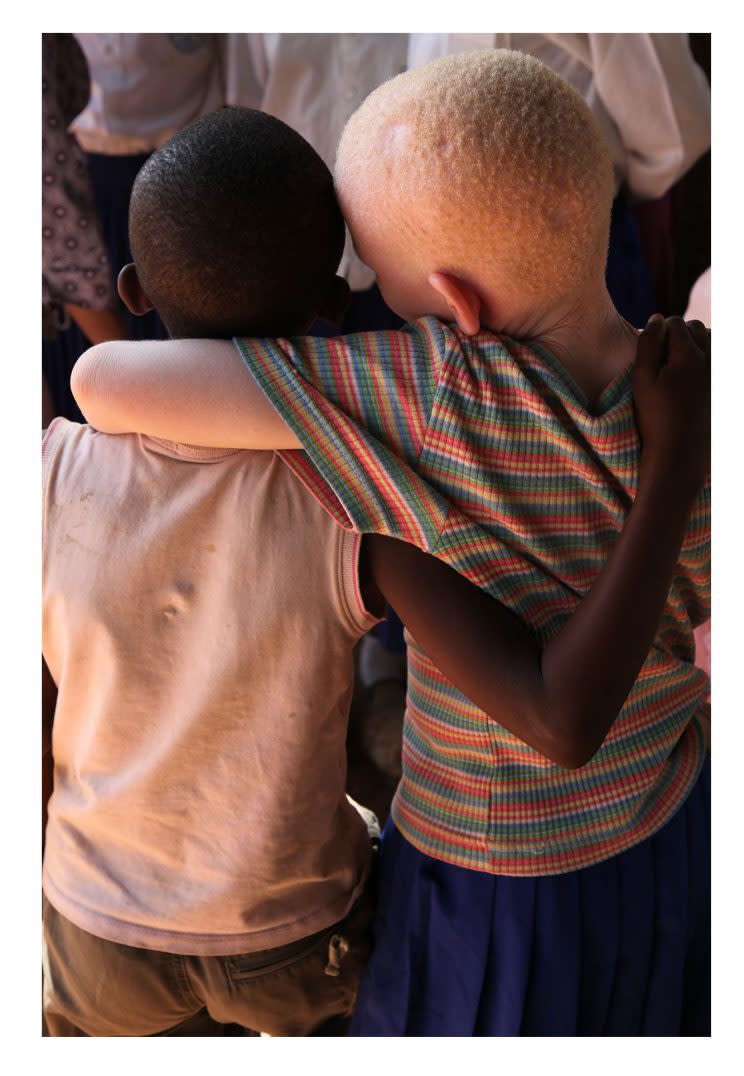

Meet the People Bringing Albinism Out of Shadows

The highlight of Ikponwosa Ero’s upcoming trip to Africa will be a stopover in Nairobi, Kenya, to meet with the winners of a unique beauty pageant that took place there recently, in which every contestant had albinism, an inherited, recessive genetic condition characterized by little-to-no production of melanin.

The pageant generated a huge amount of press within Africa — where people with albinism are subject to prejudice and persecution — and internationally. Ero, who is the United Nations’ first-ever independent expert on the enjoyment of human rights by persons with albinism and who has albinism herself, could not be happier.

“It’s great that the pageant was covered so widely, particularly in Africa, where everyone is searching for positive news about albinism,” she tells Yahoo Beauty. “I hear that Mr. and Miss Albinism Kenya feel that the pageant has changed their self-perception tremendously, and it would be wonderful to see this initiative replicated elsewhere across Africa, because anything in the realm of entertainment always strikes home far better than any other initiative.”

For photographer Rick Guidotti, the Nairobi pageant marks a new milestone in society’s acceptance of beauty in nonclassical iterations, an endeavor that’s close to his heart and that he has been a key player in for close to a decade.

Guidotti’s photos of people albinism were featured in a Life magazine spread and were the genesis for Positive Exposure, a movement that began in the late 1990s to shed light on and “rehumanize” people with albinism and other genetic conditions.

“As a fashion photographer, I was always told who was beautiful, who was face of the moment, but as an artist, I see beauty everywhere — not just in industry standards or on the covers of magazines,” he says.

Albinism, like other genetic conditions, has long been treated in an encyclopedic fashion, as an anomaly to be studied clinically. Sadly, that mindset has also prevailed among those who have it, Guidotti says.

“The first girl [with albinism] that walked in to be photographed had her shoulders hunched, her head down, and zero self-esteem,” he says. “I went with her as I did with all supermodels: I held up a mirror and said, ‘Look at yourself — you are magnificent.’ Something tilted; she put her hands on her hips and exploded into a smile that lit up all of New York City. She created the philosophy that drives Positive Exposure: the need to change the way she saw herself. Her community needed to see it, and that is how change happens across society.”

A community under siege

The Nairobi pageant, organized by the Albinism Society of Kenya, took place in large part thanks to the efforts of Issac Mwaura, Kenya’s first and only member of parliament with albinism.

Mwaura himself is emblematic, Ero says, and a testament that governments across Africa are committed to change.

The African member countries of the U.N. in Geneva, Switzerland, with support from their neighboring nations, led the efforts to set up an independent group within the Human Rights Council for people with albinism. The group works across Africa to end the attacks against people with albinism as soon as possible, Ero says, to raise awareness about albinism through education and to develop specific programs so that people with albinism can enjoy the same human rights as anyone else.

The task at hand is not easy, Ero says, because across Africa (and elsewhere in the world), albinism is still deeply misunderstood, both socially and medically. And in Africa particularly, there are many superstitions about people with albinism that foster marginalization, social exclusion, and persecution.

People with albinism are often killed for their body parts, which are then sold to witch doctors because they are believed to bring good luck. Attackers also ransack graveyards to steal body parts from deceased people with albinism.

According to data collected from 26 African countries by Under the Same Sun, a Canadian advocacy group working to end persecution against people with albinism, 187 people were killed between 2012 and 2016, and 314 were attacked — raped, mutilated or abducted, among others — in the same time period.

The numbers are likely much higher, the organization states, since many cases are never reported.

The statistics make Salif Keita shudder and bring back memories of the many difficulties he faced during his childhood and adolescence in the West African nation of Mali.

Keita, an internationally acclaimed musician, and his sister were both born with albinism.

“My father blamed my mother,” he says. “It was extremely difficult — in school, everywhere.”

Keita wanted to become a teacher, but no government-run schools in Mali would hire someone with albinism.

“I became a musician by default, he says, “but without music, I don’t know what I would have done.”

Even though she grew up in an educated, middle-class family in Nigeria, it was still tough for Ero as a person with albinism. It wasn’t until her family emigrated to Canada in the 1980s that she began to feel better about herself, she says, and to experience a sense of self-worth.

North American progress

But even in North America, it has not been easy for people with albinism.

They may not face persecution, but it wasn’t that long ago that people with albinism like the Muse brothers, two young African-Americans in the Jim Crow South who were kidnapped and forced to join a traveling circus and are the subject of a new book by journalist Beth Macy, were regarded as oddities and subjected to ridicule and mockery.

And when William Black, a 43-year-old cafe owner in Salt Lake City, was growing up, he was teased and picked on for the way he looked. He eventually stood up for himself, but being in a minority was not easy.

Things have thankfully changed, though, with respect to both social acceptance and visibility of people with albinism, Black says.

“I think the younger generations are more accepting of different people than when I was younger, and now we see more diverse cultures, so different is not as different as it used to be,” Black says. “I have met over 50 other albinos in my adult life. In my childhood, I knew of two others. I like what is out there now.”

Black has much to say for the work done by the East Hampstead, New Hampshire-based National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation (NOAH) in raising awareness about albinism and advocating for people with it.

Founded in 1982, NOAH has worked hard to erase the stigma associated with albinism, says Michael McGowan, the organization’s executive director, particularly in the entertainment industry, where for decades, albinos were portrayed as villains.

In 2006, NOAH scored a huge coup by pressurizing the producers of The Da Vinci Code to not portray the film’s evil character as someone with albinism.

“We wanted to make the point that until that time, every single depiction of albinism in the history of film — and there were about 70 or so at the time — was negative, and they showed an unreasonable, unrealistic, unsympathetic person, never the opposite,” McGowan says.

NOAH has also worked hard to help people with albinism overcome their self-stigmatization, which for many remains a great hurdle.

“I’ve been a part of the NOAH community for a while, and I have seen a huge change, particularly with the advent of social media, and people are not buying into the ‘evil albino villain stereotype’ anymore,” Guidotti says. “But we’ve still got a long way to go, particularly with respect to kids who are different being violently bullied. Bullying leads to self-stigmatization.”

Case in point, 8-year-old model Ava Clarke. The stunning child has graced the pages of Boom, VIP, and Denim magazines and worked with celebrity photographers. The young beauty has also caught the eye of casting directors and starred in Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” and walked the VMAs red carpet with her.

A photo posted by AVA CLARKE (@theavaclarkedotcom) on Oct 23, 2016 at 3:22pm PDT

Emerging from the shadows

This year, almost 1,000 participants attended NOAH’s annual conference.

“I cried,” says Ero. “That was the final step I needed to come out of the shadows, to think I am normal here, because the discussion was not about genetics; it was about life, experiences.”

She hopes that the same thing will happen in Africa one day.

The momentum is already positive: African governments are committed to the mission, supporting programs to educate people about albinism and providing the health care services — vision care and free sunscreen, among others — that people with albinism need. They are also working to create more educational and professional opportunities.

In countries like Malawi, where the U.N. has sounded an alarm call for the persecution of people with albinism, systems to encourage better reporting of attacks have been beefed up and changes are being made to the criminal code.

More important, though, Ero says, Africans want to learn.

“Africa has always known there was a problem, but the willingness to know about albinism and the surrounding issues is high,” she says.

Let’s keep in touch! Follow Yahoo Beauty on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest.