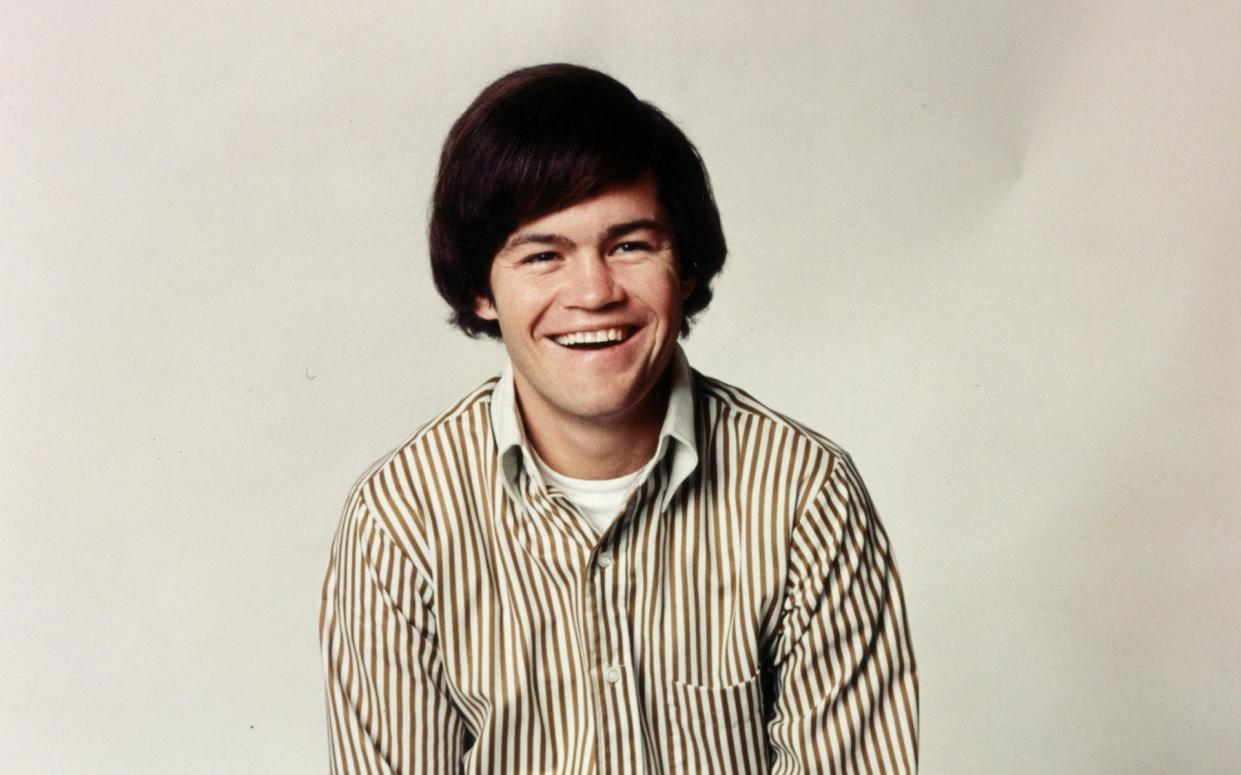

Micky Dolenz: ‘Unlike the Americans, the British understood The Monkees’

“Oh God, it was so embarrassing!” cringes The Monkees’ Micky Dolenz, as he recalls standing in the wings on his band’s 1967 tour watching their support act – the Jimi Hendrix Experience – repeatedly booed off stage.

“Jimi and the guys would be out there, performing with all this amazing, theatrical virtuosity, y’know? Playing Purple Haze, Foxey Lady, guitar behind his neck, playing with his teeth. But the kids in the audience were just screaming: ‘WE WANT MONKEES! WE WANT MONKEES!’ night after night.” He sighs. “It must have been incredibly frustrating for Jimi.”

A few months later, however, on August 18 1967, Hendrix supported the Mamas and Papas at the Hollywood Bowl – a gig that launched him as an international superstar. An unheard recording of that pivotal performance is now being released for the first time. Dolenz chuckles at the idea that “we might have helped get Jimi some attention... but I suspect he would have done just fine without us!”

Dolenz, now 78, is the last surviving member of The Monkees, the Made-for-TV band once ridiculed as “The Prefab Four”. “But only,” he laughs, “by people who took their rock music very seriously. We were silly and irreverent, in the tradition of British comedians like The Goons. So the Brits got us more than the Americans. The Beatles got us. John Lennon said we were like the Marx Brothers… but with songs written for us by some of the greatest songwriters in America. Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Neil Diamond. Oh man!.”

Calling from his home in Southern California where he lives with his third wife of 21 years Donna Quinter-Dolenz, an artist, Dolenz still sounds as buoyant as ever. He reminds me that many people forget that The Monkees were “conceived as a show about an unsuccessful band who wanted to be the Beatles. It resonated because the characters were like so many young people at that time, trying to play music in their garages, dreaming of fame. I wasn’t a drummer. I played the guitar – I played Johnny B Goode for my audition. But I had enormous fun playing the part of a whacky drummer on the show before I eventually learned to play the drums for live shows…”

Born in 1945 in Los Angeles, where he grew up, Dolenz describes himself as a “child of showbiz”. His father (who died when he was just 17) was actor George Dolenz and his mother, who managed his early career, was Janelle Johnson. At 10, little Micky was cast as the star of TV show Circus Boy, about the adventures of a young orphan in the circus. After the show was cancelled he planned on a career as an architect, thinking “if that didn’t work out I could fall back on acting or music”.

He then formed a band called Micky and the One-Nighters and auditioned for The Monkees. Producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider played smart with the casting, famously and casting actors Davy Jones and Micky Dolenz with folk musicians Michael Nesmith and Peter Tork. It was all a huge laugh but by the second year of filming Dolenz tells me the schtick was “getting old. How many times can Davy fall in love with a girl and get chased around the set?”

It was Dolenz’s passion for rock’n’roll that brought Hendrix into their orbit. “I was in New York when someone told me I should go down to the village, to Cafe Wha?, and see this kid who played guitar with his teeth. He was amazing. Then I was at the Monterey Pop Festival [1967] and there was the Jimi Hendrix Experience. I was backstage and there was some argument about whether Jimi or The Who should go on first because they both destroyed their instruments. The Who were more destructo but Jimi set fire to his guitar, so he went on first…”

It was this “showbiz” aspect of the Hendrix show that made Dolenz think Hendrix would be a good support act for The Monkees a month later. Although Hendrix famously dismissed The Monkees’ music as “dishwater”, Dolenz tells me that “at the time” he never heard Hendrix, whom he describes as “shy, quiet, street smart but naive about business”, say a bad word about their output.

Hendrix would die from asphyxia after overdosing on barbiturates, aged just 27, in September 1970. All these years later, the loss of his friend still gives Dolenz pause. “Back then people died from accidents and naivety.” Drugs, he tells me, were part of “an amusement park, each drug was a new ride. Someone would say, ‘I met this guy who had this cool new purple stuff’’. One day you can try the wrong thing…”

Another pause. “So much of it, with Jimi, with my good friends Mama Cass and Keith Moon, they just didn’t know. I’m so grateful because I think of many times I could have died. My mum always said I had a guardian angel on my shoulder that meant I could ride right up to the edge of a cliff but not go over it. But really it’s just the luck of the draw.”

Jackson Browne once described going over to Monkee Peter Tork’s house and seeing Tork’s girlfriend playing drums naked with Hendrix. Does Dolenz remember that? “Nooo! Wow… but I mean it could have happened. The nakedness was, like the drugs, very naive. Peter’s house was like a nudist camp, not a brothel. It was very innocent. Summer of love, Southern California, hot weather. Peter had a lovely pool and people would just walk around naked because it was the 60s and that’s what you did!”

Dolenz once described fame as “burning a hole in our souls”. Today, he is more measured, particularly on the subject of 1968 psychedelic black comedy Head, co-written by Jack Nicholson, which skewered everything from Hollywood and the music business to The Monkees themselves. While his bandmates later regretted their involvement, which was panned by critics who believed the film “destroyed” the band, Dolenz is proud of making a statement “buck[ed] against the studio system.”

In particular, Dolenz enjoyed the moment when he was playing a cavalry officer in a sketch that was “a pastiche of the classic western” and he got to say: “These arrows are fake, this pain is fake, this is ALL FAKE!” Then he reminds me that he burst through the painted set and walked free of the band.

Tork later complained that the movie never set the band free. “So make your choice and we’ll rejoice/ In never being free!” ran the closing number. Davy Jones described the film as a black star that sank their reputations. But Dolenz says he knew he could maintain a career as a businessman, producer and director, working most famously on the early 80s TV series Metal Mickey about a robot housekeeper.

These days, Dolenz keeps busy. He still tours Monkee songs. “I don’t think I thought I’d even be alive at 78 let alone still on stage!” he marvels. But he’s equally at peace in the home workshop he shares with the youngest of his three daughters from his current marriage, Georgia. (His eldest daughter, Ami, is from his first marriage with the late model Samantha Juste. His second marriage was with couples therapist Trina Dolenz.)

Micky and Georgia make and sell furniture as “Dolenz and Daughters”. He tells me that he’s always made things. “A gyrocopter and a few hang gliders I flew in the 1960s… These days it’s more chess sets and guitar stands.” He promises to fix my broken rocking chair the next time he’s in the UK.

I hang up with my love of The Monkees untarnished. Dolenz is one of the nicest, smartest celebrities I’ve ever encountered. He tells me that’s because at heart he’s “a nerd… I’ve got science books by my bed. I’m not that interested in me.” And he suspects Hendrix was the same. And then Dolenz sings me a little of Purple Haze. His gentle, hopeful voice wobbles through the psychedelia. It’s beautiful. “Thanks, man,” says Dolenz. “I know, right?”

Jimi Hendrix Experience: Hollywood Bowl August 18, 1967 is out now via Legacy Recordings / Sony Music Entertainment