Model, Photographer Lee Miller’s Career Subject of New Exhibition and Hollywood Film

Model, fine art photographer, World War II photojournalist, cookbook author — Elizabeth “Lee” Miller’s life could not be defined by one metier.

But one force that was integral to her creative life was her 40-year relationship with her second husband, the English Surrealist painter and Pablo Picasso biographer Roland Penrose. Now a new exhibition at Gagosian, titled “Seeing Is Believing: Lee Miller and Friends,” magnifies their works and relationship with photographs by both, as well as works by their artistic friends like Max Ernst, Dora Maar, Man Ray, Henry Moore, Picasso, Joseph Cornell and others.

More from WWD

Edward Enninful to Receive the Trailblazer Award at Fashion Awards

Lily-Rose Depp Among Women in Film Uniting at the Academy Women's Luncheon, Presented by Chanel

Letters, photo albums and other memorabilia help visitors to circumnavigate the couple’s inner circle. On view at the Madison Avenue gallery through Dec. 22, the exhibition coincides with a resurgence of interest in Miller’s life. “Lee,” a feature film that Kate Winslet stars in and has produced, is based on Penrose’s “The Lives of Lee Miller.” Alexander Skarsg?rd and Marion Cotillard also headline the flick, which debuted this fall at the Toronto Film Festival.

In addition, Farleys House and Gallery, Miller’s former home in the Sussex countryside, is extending its hours to welcome more visitors three days a week from April through October.

In New York for the opening, Miller’s granddaughter Ami Bouhassane attributes the interest to Miller being “very relatable. Yes, she was born more than 100 years ago, but her life and the issues that she dealt with, her imagination and the ways that she worked in her career are still quite inspiring.”

The Poughkeepsie, N.Y.-born Miller, who died in 1977 at the age of 70, started out as a fashion model and landed her first American Vogue cover at 19. Once nearly hit by a car on the streets of New York, Miller avoided injury thanks to the quick reflexes of another pedestrian, who happened to be the famed Condé Nast photographer Edward Steichen, who later jump-started her career. However, in the late ’20s after appearing in an evening gown in a Kotex ad, “No one really wanted the Kotex girl modeling their haute couture any more,” said Bouhassane, adding that gave Miller an excuse to return to Paris.

Steichen, who had shot the photo for Kotex, gave Miller a letter of introduction to his friend Man Ray in Paris. “She then turned up on his doorstep and told him that she was going to be his student. Within a year of working with him she started up her own studio, which was incredible for a woman in 1930 to be running her own commercial photography studio,” her granddaughter said. (As a model, Miller was known to pepper Steichen and other photographers with questions about technique, which would become useful when she herself moved behind the camera.)

Although the American Embassy encouraged Americans in France to return to the U.S. during World War II, most of Miller’s friends were in Paris, and she felt that she couldn’t abandon them, Bouhassane said.

A chance meeting with Penrose led her to move to England at the outbreak of the war. Miller first volunteered and then secured a work visa as the lead fashion photographer for British Vogue. “You can see in her letters to her parents that she feels that she’s not doing enough to support the war, taking photos of shooting hats and handbags,” her granddaughter said, adding that that was despite the fact that her British Vogue work was “soft propaganda,” in that it was used to encourage British women to join military agencies or for factory workers to do their part.

When America joined the war, Miller had the opportunity to become a war correspondent and took it. After the liberation of the concentration camps at Dachau and Buchenwald, she was among the first to document that, Bouhassane said. (After photographing the liberation of Dachau in 1945, Miller was photographed by David Scherman bathing solemnly in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub.) Her granddaughter said of her fearlessness, “She was just determined that people should see what was happening. She was determined to be a witness to make sure that the truth came out.”

That quest for truthfulness may have stemmed from Miller having been raped at the age of seven in 1914, a time when such cruelties were concealed. “Her mum wasn’t very well. So she was sent to stay with some friends of the family when it happened,” Bouhassane said.

Although Miller never disclosed that to her husband or son Antony Penrose, her brothers spoke of it years later. “Unfortunately, she was infected with a venereal disease. This was before penicillin had been invented and she got gonorrhea. She had to have these very painful treatments. Her brothers were made to leave the house so they wouldn’t hear her screaming.”

Her war photography took its toll, greatly affecting Miller and causing her to suffer from depression, Bouhassane said. “In those days, no one knew anything about that level of mental health, and we are still learning about it. In those days, it was called ‘shell shocked,’ If you couldn’t deal with it, you were supposed to have a whiskey. If you still couldn’t deal with it, you were supposed to have another one. The accepted way of dealing with this mass trauma that the whole world had suffered was ‘Put up and shut up,’ which we know now was not a good thing,” her granddaughter said.

Miller buried all of her photojournalistic photography in the attic of Farleys House and then reinvented herself as a gourmet cook. In honor of turning 50, Miller enrolled in Le Cordon Bleu in Paris and by the early ’70s had become a celebrity chef. Her cookbook “Lee Miller: A Life With Food, Friends and Recipes” will be re-released in the U.S. nexxt year and a select number of copies are being sold in Gagosian’s Upper East Side store.

After Miller died, Antony Penrose’s wife Suzanna discovered Miller’s trove of photos, negatives and manuscripts in the attic and showed them to Penrose, who had had no idea that his mother had been a war correspondent. Farleys House and the archives are overseen by the father-daughter team. Penrose did remember very clearly that biographers of Jean Cocteau, Man Ray and other artists would visit Miller for their research since she knew them so well, according to his daughter. “They would ask her about her relationships with them. She would always defer, or change the subject to make it about something else.”

The Gagosian show highlights Miller’s and Penrose’s artistically well-rounded union amid their friends. Bouhassane approved of that portrayal noting, “We have always fought against her just being this Man Ray sidekick or slutty, pretty muse that a lot of famous women got pigeonholed as.” Co-curator Jason Ysenburg firmly places Miller in the nexus of that group of friends, “so that she is definitely not peripheral and the pretty girl on the edge. You can see the inspiration and the collaboration between them too,” her granddaughter said.

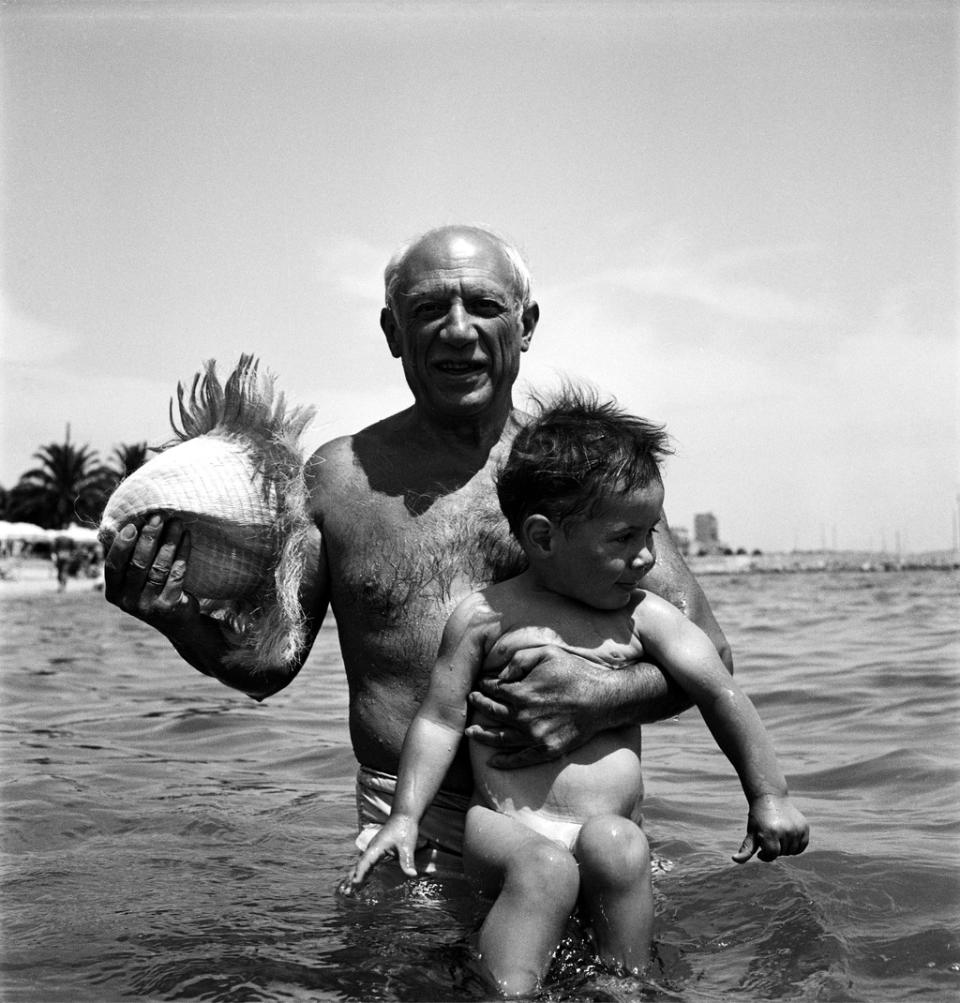

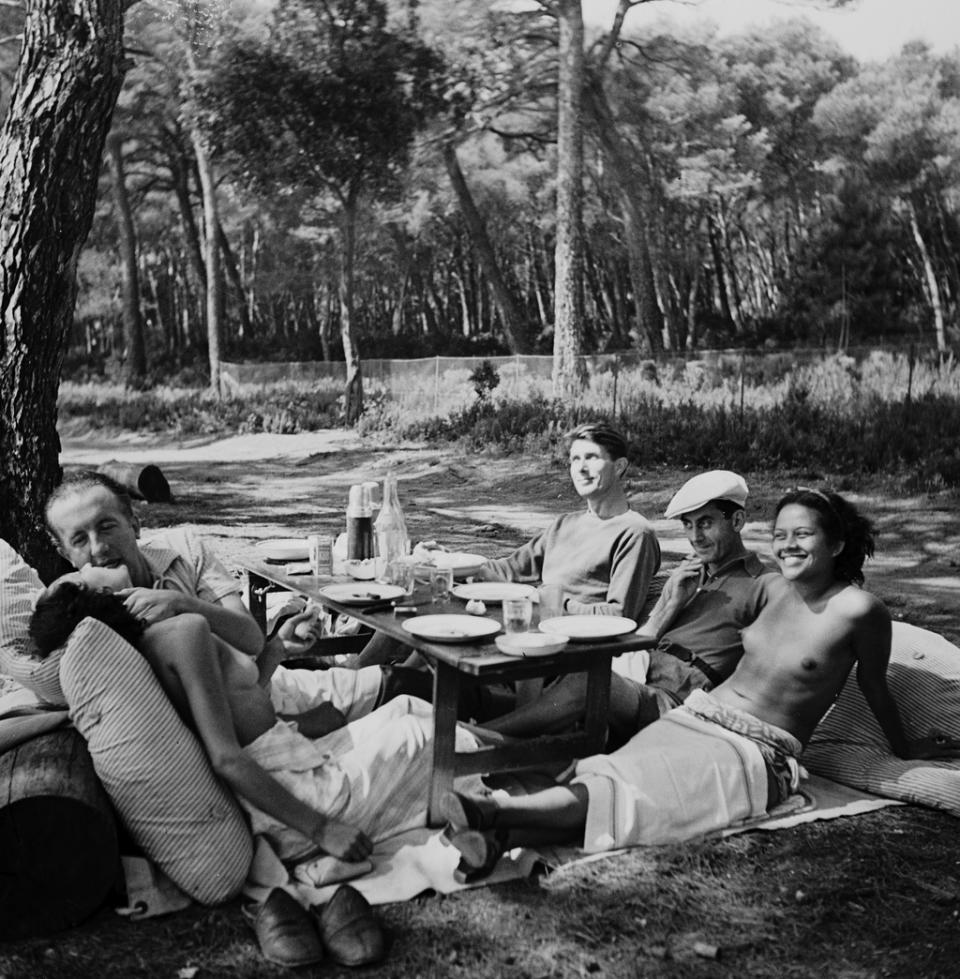

Despite having grown up surrounded by Miller’s work, she said her favorites at Gagosian are the snapshots from Miller’s photo albums. “I just love looking at these photos of people goofing around on the beach having fun, and then suddenly realizing, ‘Oh, that’s Dora Maar. And that’s Picasso and Man Ray.’ It kind of just makes them real. They’re real people rather than these big names that you’ve heard of all of your life,” said Bouhassane, who has consulted on the feature film with her father for the past eight years.

She hopes the Gagosian show and the film will generate more conversation about mental health and encourage people to explore more of Miller’s photography, including her war work. “She constantly reinvented herself and never really allowed anything to beat her,” Bouhassane said. “She was born in 1907. One of the amazing things that her parents did for her was to treat her like her brothers. That was pretty unusual in those days, when you were brought up to be a good little wifey. Her base line was equality. She was trained from a young age that she could do the same thing as boys.”

All in all, showing Miller’s career to a wider audience is worthwhile, when she inspires others to create, makes changes in their lives or to challenge the status quo, Bouhassane said. “Having a film inspired by her is pretty awesome.”

As for what Miller would make of all this new-found attention, her granddaughter said, “I think she would think it was hilarious. She would definitely be excited.”

Best of WWD