How the mods and the rockers whipped up a media frenzy

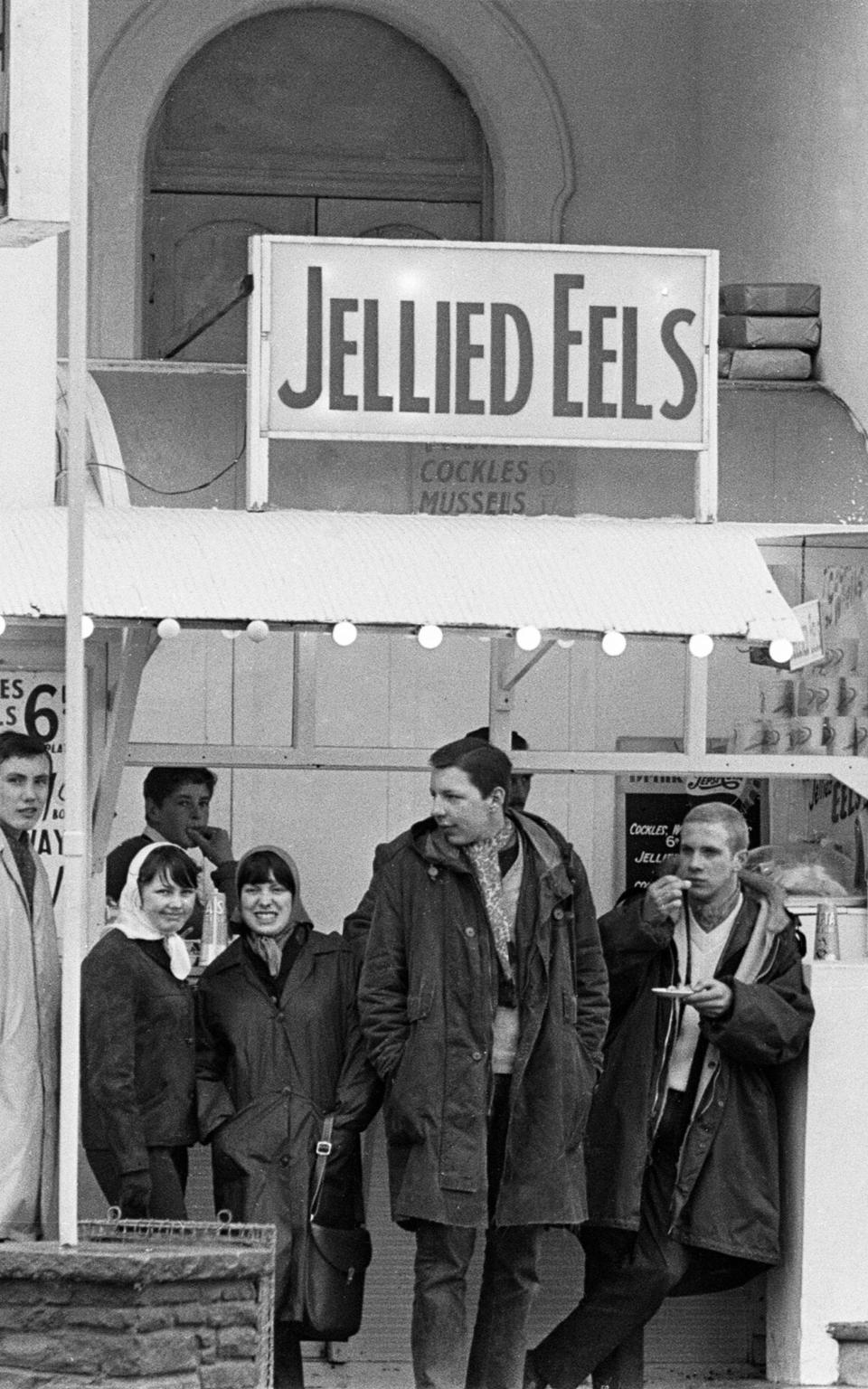

“Clacton on Sea,” proclaimed an advert in the Daily Mirror on Easter Saturday, 1964: “Seven Miles of Golden Sands. Beautiful Gardens. Fast Electric Trains from London.” Yet any holidaymakers who made the trip probably wished they had stayed at home, not just because it was the coldest Easter since 1883, but primarily on account of the visiting rival groups of young Londoners whose behaviour dominated the following day’s newspaper headlines.

“‘Wild Ones’ Invade Seaside – 90 Arrests” said the Mirror’s front page, drawing a parallel with the 1953 Marlon Brando biker film, blaming the trouble on “1,000 fighting, drinking, roaring, rampaging teenagers on scooters and motorcycles”.

Rival paper the Daily Herald bizarrely claimed that the hooligans had come there to see a gig by family-friendly Merseybeat outfit Freddie and the Dreamers – a band so unthreatening that they appeared on the children’s TV programme Blue Peter that year singing to the show’s dog, Petra. Nevertheless, the Daily Herald, like many newspapers, painted a lurid picture of Armageddon-by-the-sea.

“They smashed windows and marched dozens abreast along the promenade, jostling holiday-makers and beating-up anyone who protested. A middle-aged man was thrown over a 20ft-high ornamental bridge.”

Clacton police justifiably argued that “many reports of the weekend disturbances had been exaggerated”, yet the following day brought fresh shock-horror headlines of more arrests at Clacton, and disturbances at Margate in which a youth was stabbed. The newspapers now made reference to “Mods and Rockers”, and mentioned the drug-use among those teenagers – especially the amphetamine-barbiturate tablets sold on prescription as Drinamyl, popularly known as purple hearts – despite the fact that the self-same product was being legally doled out among the adult population by GPs, giving rise to another nickname, “mother’s little helper”.

The participants talked freely to journalists; it was “a giggle”, one rocker told a reporter, and other teenagers who had missed out looked for the next opportunity to gather at the seaside. Thus relatively minor scuffles, dealt with mostly by fines, were stoked by the media into a self-fulfilling prophecy of periodic copycat outbursts of violence along the south coast until the late summer, flaring up at Margate and Brighton on the Whitsun bank holiday weekend, May 16–18, then finally at Hastings over another bank holiday, August 1–3.

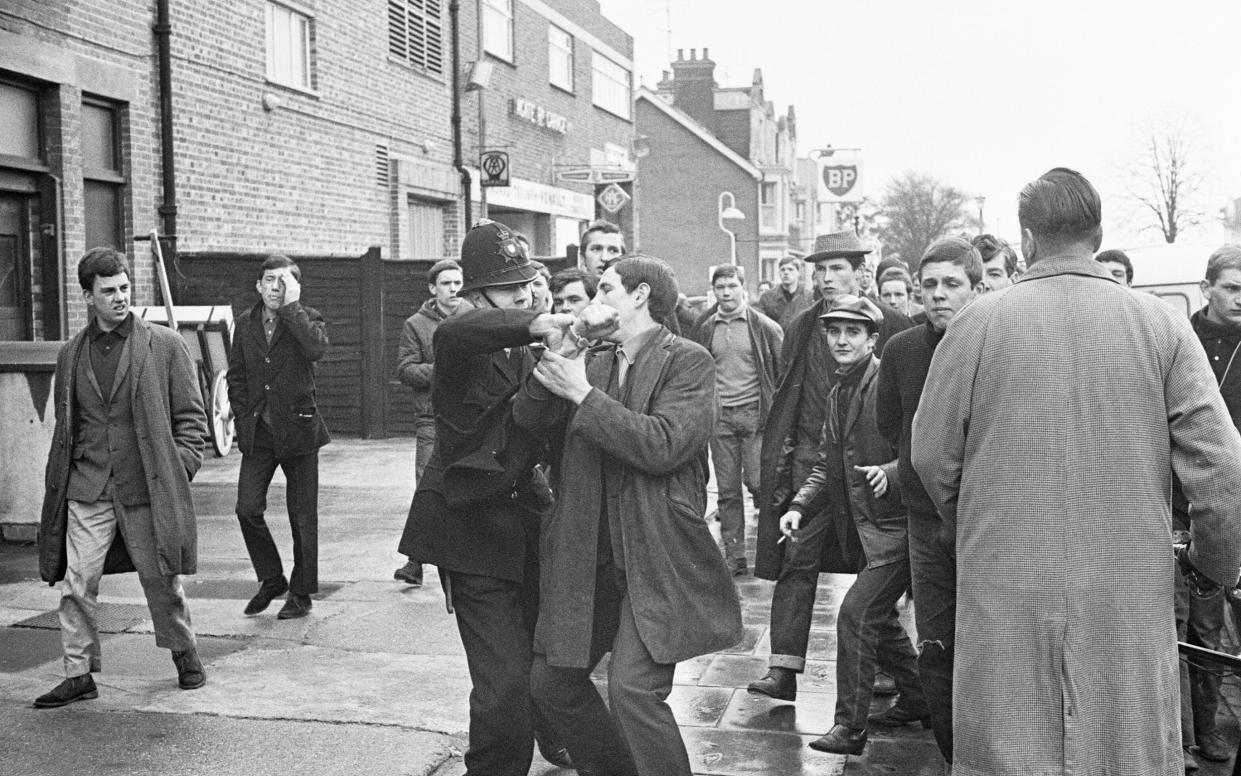

Press photographers and a Pathé newsreel team captured the violence enacted by those who had read in the press about earlier confrontations and probably felt duty-bound to deliver the goods. Such stories were hard to ignore that summer, particularly the ugly front-page image of a mod on Brighton beach kicking a prone rocker in the head. Many bystanders would have been old enough to remember Churchill in 1940 saying that “we shall fight on the beaches”, but presumably this was not what he had in mind.

The newspapers spent 1965 predicting further beachside clashes that failed to materialise, and commentators often conflated the two factions, blaming this strange entity “Mods-and-Rockers” for numerous outbreaks of petty violence across the country.

Although 1964 was the flashpoint, the rivalry between these two groups had been slowly building for a year or so – unsurprising given that they favoured distinctly different types of clothing, hairstyles, motorised transport and music. A decade earlier, ritualised gang fights took place in London between assorted Teddy boy groups who outwardly looked the same, simply on the grounds that they came from different areas of the city. In October 1963, the Whitstable Times had stated that mods were “a type of teenager who is waging ceaseless war against the rockers”. When the trouble finally blew up in Clacton six months later, sparked largely by groups from London who already disliked each other, it probably came as little surprise to those on either side.

Both groups had actually been hovering on the edges of popular culture for some years. In 1959, Clancy Sigal for The Observer interviewed a north-London gang called The Punchers, who identified as modernists, owing to their love of modern jazz (though their tastes later extended to R&B and soul).

“It’s the new trend with them, cutting their hair short à la St Germaine de Pres [all sic] and listening to the Modern Jazz Quartet and searching hard for ‘intellectual’ words,” Sigal wrote.

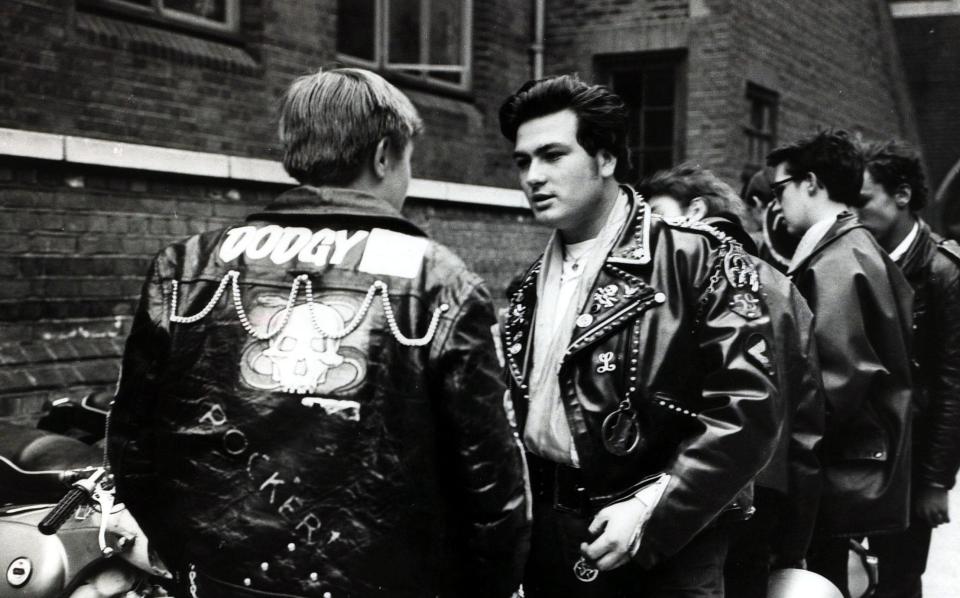

Rockers, favouring British motorbikes, leathers and the music of Elvis, Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent, could be found around the same time at places like the Ace Café on London’s North Circular Road.

Representations in popular culture included Alan Hunter’s Inspector George Gently encountering a similar group of rockers in the novel Gently Go Man (1961) who spoke in jive talk, prompting the Sunday Telegraph’s reviewer to respond in kind, saying, “You’ll make with this book like crazy”.

Gradually, the word “mod” became just a simple shorthand for anything new or trendy, while many erstwhile rockers slowly adopted the US-imported Hells Angels look, but in 1972, Stanley Cohen’s landmark youth culture book, Folk Devils & Moral Panics, shone a torch at the hysterical process by which the mods and rockers of the 1960s had been demonised.

“The mods and rockers symbolised something far more important than what they actually did,” Cohen wrote. “No one wanted depressions or austerity, but messages about ‘never having it so good’ were ambivalent in that some people were having it too good and too quickly.”

Just as this appeared, The Who began recording an album telling the story of a fictional mod called Jimmy, released the following year as Quadrophenia. In 1978, the band produced the film adaptation, directed by Franc Roddam, which appeared in 1979. Coming from one of the original mod bands, it unsurprisingly sides with the scooter-riding fraternity against the rockers. Being a mod mainly seems to involve marching along the promenade chanting “We are the mods” and frightening the horses, and here again the parallels with 1970s football supporter behaviour are obvious.

Original mods and rockers, and also new ones inspired by the film, have regularly made the pilgrimage out to the coast over the years and continue to do so, but these are usually peaceful occasions with a distinct absence of tabloid headlines. Now, 60 years after the original clashes, there seems to be no precise modern equivalent.

Five or six years ago, I was walking through Hyde Park one summer afternoon, and ran into several hundred young people, all armed with powerful “super-soaker” water pistols, brought there by the internet for a pre-arranged confrontation, which degenerated into a series of ugly running fights with van-loads of police. Not a clash between two groups who had consciously chosen their own differing uniforms, transport and lifestyle, it made barely a stir in any newspaper, and was forgotten within days. We can look for parallels, but the era in which young people define themselves primarily as part of such tribes and subcultures seems to have passed.

In 1964, the nation had just two television channels, while in radio, there was only the BBC, although several pirate stations debuted that year, so a story such as the Easter skirmishes at Clacton could dominate the news narrative in a way that is just not possible with today’s profusion of outlets.

A selection of genuine mods had been interviewed between January 1963 and June 1964 by Woman’s Own journalist Jane Deverson and the writer Charles Hamblett for the ground-breaking book-length youth study Generation X (1964), in which the sense of personal identity conveyed by the subculture was paramount, bound by self-imposed rules and standards: “If you’re a mod you’re a mod 24 hours a day, even working with other people you’re still a mod… But I’m past it now, I’m too old, 19. You’ve got to be 16 to be a mod.”

By that reckoning, you’ve now got to be 74 to be a mod. Young people today, understandably, have other things to do.

‘Teddy Boys’ by Max Décharné is published by Profile