Mohamed Al Fayed Remembered for Princess Diana Controversy and Reviving Harrods and The Ritz Paris

LONDON — Mohamed Al Fayed, the colorful and controversial former owner of Harrods who died last week at 94, was buried next to his son Dodi on the family estate in Surrey, England, following a private funeral over the weekend.

The self-made Egyptian tycoon, who died following a long illness, grew up in poverty in Alexandria, Egypt and built his fortune on shipping, real estate and construction. Al Fayed had an estimated net worth of 1.70 billion pounds, according to the 2023 Sunday Times of London Rich List.

More from WWD

At the time of his death, Al Fayed had already sold off two of the biggest brands in his portfolio, Harrods and the London soccer team Fulham FC. He still owned The Ritz in Paris.

None of Al Fayed’s four living children — Dodi died in the 1997 car crash that killed Princess Diana — was involved in the day-to-day operations of the family businesses. Coincidentally, Princess Diana and Dodi Al Fayed also died on what is Labor Day weekend in the U.S.

A divisive figure among the British establishment, Al Fayed inspired loyalty — and loathing — among employees, colleagues and fellow entrepreneurs.

Over the weekend, Fulham fans paid tribute to the late tycoon, waving farewell banners during Saturday’s match against Manchester City. The team wore black armbands as a sign of respect.

Late Friday, shortly after Al Fayed’s death was revealed, the team issued a statement on social media: “Everyone at Fulham was incredibly saddened to learn of the death of our former owner and chairman, Mohamed Al Fayed. We owe Mohamed a debt of gratitude for what he did for our club, and our thoughts now are with his family and friends at this somber time.”

The Ritz Paris issued a statement saying that “Laurent Herschbach, general manager, and the entire team of the hotel, send their most sincere condolences, support and deepest sympathy to Mrs. Mohamed Al Fayed, her children and grandchildren following the announcement of the death of Mr. Al Fayed.

“It was Mr. Al Fayed’s exceptional vision and commitment that revived the Ritz Paris to its former glory as a world-renowned Parisian institution. His dedication to the hotel, its patrons and his staff will never be forgotten,” the statement said.

Harrods has not made any statement.

Al Fayed, along with his brothers Ali and Salah, seemingly came out of nowhere in 1985 to buy Harrods and its parent group House of Fraser, outmaneuvering the Lonrho Group and its equally colorful and combative chief Roland “Tiny” Rowland (instigating a feud between the two that would trundle on for years, and result in numerous press statements and several parliamentary and government investigations). Al Fayed considered Harrods his most-prized possession; he often compared it to pyramids in Egypt. But his arrival on the scene sent London’s titled and wealthy into near apoplexy and the purchase of Harrods to them was almost akin to Al Fayed buying Buckingham Palace.

Their snobbishness was only exacerbated by the showman’s touch he brought to the store, pioneering in the U.K. the idea of retail as entertainment. He tapped actors including Richard Gere, Sophia Loren, Kim Cattrall, Cher and Pierce Brosnan to open the annual summer and winter sales, invariably posing alongside them with his Cheshire Cat smile; the photos filled the British tabloids the next day.

Then there was the dash of the ancient world he added shortly after buying Harrods, the glittering, cartoonish Egyptian Hall and escalator at a cost of 20 million pounds, or $29.6 million. The hall is decorated with busts of Tutankhamun-like figures on each floor. Al Fayed marked the opening by donning an Egyptian headdress and robes.

He once told The Sunday Times of London that he planned to own the business for the rest of his life, and that when he died he hoped to be entombed in a mausoleum on the roof of the store — a wish he expressed repeatedly.

“It’s a pyramid for me, a monument,” he told the British paper. “It is the best department store in the world.”

But while his ownership was filled with controversy and missteps, no one can argue that Al Fayed raised Harrods to a different level and, in many ways, sparked retail trends that would spread globally. He spent an estimated 400 million pounds, or $592 million, to transform what had been a tired store into an unapologetically opulent retail experience.

His management style could, at best, be described as mercurial. He showered executives with cars, apartments on Park Lane and all-expenses-paid trips. But as quickly as they won his favor, they just as rapidly — and inexplicably — lost it. One senior executive was dismissed because of the brand of suits he bought.

In more than two decades of running the store Al Fayed went through a string of managers who lasted as long as his whims.

Former Gucci Group executive James McArthur left his post as chief executive officer of Harrods less than a year after starting his role, while Martha Wikstrom, who served as managing director, stayed for less than two years.

On his regular tours of the store, employees would literally run for cover when they saw Al Fayed coming for fear he’d notice them and fire them on the spot for some imagined infraction, or berate them at the top of his voice for something he didn’t like. A few weeks after asking employees to change something, he’d ask them to change it back again.

On Al Fayed’s watch, female shop floor staff had to dress in black, and wear high heels and a full face of makeup. The employee entrance to the store had a vast room filled with rows of illuminated mirrors so that women staffers could apply their makeup in the morning, and refresh it throughout the day.

Al Fayed was known to call employees on a whim at all hours of the day or night, and he loved an off-color joke.

After one dinner with press and members of Harrods management, Al Fayed walked around the table handing out mints to all of the male guests. He insisted that they were Viagra pills.

Yet some considered Al Fayed an inspiration.

Jonathan Akeroyd, now CEO of Burberry, joined Harrods in 1988 and said Al Fayed’s presence “was felt on a daily basis. Throughout my time working at Harrods, there was always something going on. It wasn’t until 1999 that I had the opportunity to work closely with him and I got to know him well.

“He was a man with incredible humor and passion. I learnt a lot from him. He was a true entrepreneur with a vision to take Harrods into a new era and make it a global destination for luxury, which he achieved,” Akeroyd said.

Terron Schaefer, who was director of Harrods from 1986 to 1990, told WWD in 2010 that when he first joined Harrods, “they were still selling Tampax, toilet paper and notions. It had this kind of faded elegance. But Mohamed did an amazing job really adding some luster to what was kind of a tired old department store. Their motto was ‘everything for everybody, everywhere.'”

Schaefer added: “The thing I most loved about working there were the windows. There are 72 windows around the perimeter of the store and you can get the handle on anything going on inside.”

Jason Broderick, who joined Harrods in 1998 and rose to become general merchandise manager of menswear, sports and watches, said Al Fayed “pioneered a new world of luxury department store shopping that has inspired so many retailers across the globe.”

Broderick, now an executive at Dunhill, described his former boss as “a true retailer and leader who has left an amazing legacy that I’m deeply proud to have been a part of. I have so many fond memories of his leadership at Harrods.”

When Al Fayed let the top brass shine, it paid off. Empowered by Al Fayed, Marigay McKee, the store’s former fashion and beauty director, transformed both of those divisions during her long career there.

She spearheaded a string of fashion initiatives, including the creation of the International Designer Room on the store’s first floor. It launched in September 2009, showcasing 40 labels including Prada, Balmain, Lanvin, Balenciaga and Chloé.

“He was a legend, a one in a million human and a great man,” said McKee, the former president of Saks Fifth Avenue and a cofounder and managing partner of Fernbrook Capital Management LLC.

“He loved his family above all else, and had a deep love for Harrods, which was his life’s work and passion. He left an imprint on many, was generous to a fault, and a mentor and teacher to all who allowed him in. I learnt a lot from him and loved his irreverent, yet charming, sense of humor. He loved to laugh, he loved a joke, and yet his life was tinged with as much sadness as happiness,” McKee added.

She said that protecting all those close to him was Al Fayed’s mission “and loyalty was a code he lived by. He put the customer first, gave them a great experience, made a great [retail] environment, and created excitement and theater. His heart was his greatest asset, and he will be remembered by many. RIP Mohammed (Uncle Mo),” McKee said.

Al Fayed’s unique management style led to a number of controversies, and questionable decisions, at the store, which — inexplicably — had a PA system, similar to that of a mass market retailer, that would regularly blast out news of daily promotions and events.

In 2003, Al Fayed offered Krispy Kreme a large space in the food hall, much to the horror of Knightsbridge residents who would watch as crowds of tourists chomped their doughnuts on the pavement outside the luxury store.

In the mid-1990s, Harrods began charging people 1 pound (about $1.50) to use the bathrooms in a bid to deter non-shoppers from availing themselves of the facilities. Today, customers no longer have to pay.

Then there was the uproar that accompanied his decision to ban backpacks and large handbags from the store, resulting in many tourists being turned away by security. This practice was more understandable in the ’90s given that Harrods was a regular target of bombs by the Irish Republican Army.

Al Fayed ended his 25-year reign at the store in 2010, selling it to Qatar Holding, an investment company linked to the royal family of the Gulf state. He offloaded it for 1.5 billion pounds, or $2.27 billion at current exchange, including about 600 million pounds, or $906 million, in property-backed debt.

Like most London retailers, Harrods has had its ups and downs over the decades, but it has recently been prospering under the current owners.

In the fiscal year ended January 2023, Harrods bounced back from the pandemic, with turnover rising 42.9 percent to 831.6 million pounds, and profit after tax surging to 433.3 million pounds from 41.7 million pounds.

Al Fayed was born in 1929 in Roshdy, a poor neighborhood in Alexandria in the Kingdom of Egypt as it was called before the Egyptian Revolution of 1952. His father was a primary school teacher, but a life of poverty was not for him, and the ambitious Al Fayed chose a different path.

In Egypt he began as a street seller, hawking carbonated drinks, and later sewing machines, before working for Adnan Khashoggi, the Saudi Arabian businessman and arms dealer who was no stranger to controversy or the high life himself. In the early 1950s, Al Fayed married Khashoggi’s sister Samira, and the couple had one son, Dodi, before separating.

In the ensuing years, as Al Fayed built his empire, he was often economical with the truth. His website used to claim he was born in 1933, but Britain’s Department of Trade found the year to be 1922.

In the ’70s, the tycoon added the fancy prefix “Al” to his surname to give it more of a pedigree. He also fudged details about the source of his family’s wealth before buying Harrods and its then-parent House of Fraser.

A government report into the Harrods deal fell just short of calling Al Fayed and his brothers liars about the size of their fortune, although the government took no legal action and could never find out where exactly the Al Fayeds got the funds to buy the store. Rumors ranged from the Sultan of Brunei to a string of far-from-savory characters.

Private Eye, the satirical British news magazine, nicknamed him the “Phoney Pharaoh.”

Before venturing into the world of retail, he had a shipping company with his brothers that was based in Egypt before moving it to Genoa, Italy, with offices in London.

In the mid-’60s, he cozied up to Haitian leader Fran?ois Duvalier, otherwise known as Papa Doc, to form an oil refinery called Fayed-Duvalier. Al Fayed left Haiti for London — after just six months — when he was presented with oil that was disguised as molasses.

In London, he started a relationship with Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, an Emirati royal and a founder of the United Arab Emirates. Al Fayed helped him to transform Dubai by introducing him to construction companies such as Bernard Sunley & Sons, Taylor Woodrow and the Costain Group, where he became a director and 30 percent shareholder.

Al Fayed’s big step came into luxury in 1979, when he bought the near-bankrupt Ritz hotel in Paris for $30 million.

He spent about $250 million on a 10-year renovation without ever closing the hotel’s doors. He enlisted the help of a French architect from 1980 to 1987 to spruce up the establishment, from top to bottom, including the famous Ritz Bar, where Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald famously drank in the 1920s. The bar was added in the Cambon wing, across the street from Chanel.

In 1984, after snapping up The Ritz, Al Fayed along with his brothers, purchased a 30 percent stake in the House of Fraser group, which included Harrods, from Rowland. The following year, they bought the remaining 70 percent.

Al Fayed and Rowland had a tumultuous relationship, throwing daggers at each other in the press any time they had the opportunity. In the ’80s, Al Fayed accused Rowland of campaigning against him in The Observer newspaper, which Rowland then owned, while Rowland had the British government’s Department of Trade and Industry launch an investigation into Al Fayed and his activities.

No action was taken as part of the investigation — though it did find Al Fayed and his brother Ali misrepresented the extent of their wealth when they bid for House of Fraser.

There was a long history of such scandals: In 1994, Al Fayed was involved in what came to be known as the cash-for-questions scandal, which ultimately resulted in the resignation of two British MPs.

Controversy dogged the stubborn Al Fayed, who had a difficult time letting go of his grievances, and his grief over the death of his eldest son Dodi in the Paris car crash that also killed Princess Diana.

Many upper-crust Brits refused to enter its doors after Al Fayed bought the store, and those negative feelings toward him only grew with his outspoken campaign to prove that the deaths of Dodi and Princess Diana were ordered by the British royal family because the couple was about to be married.

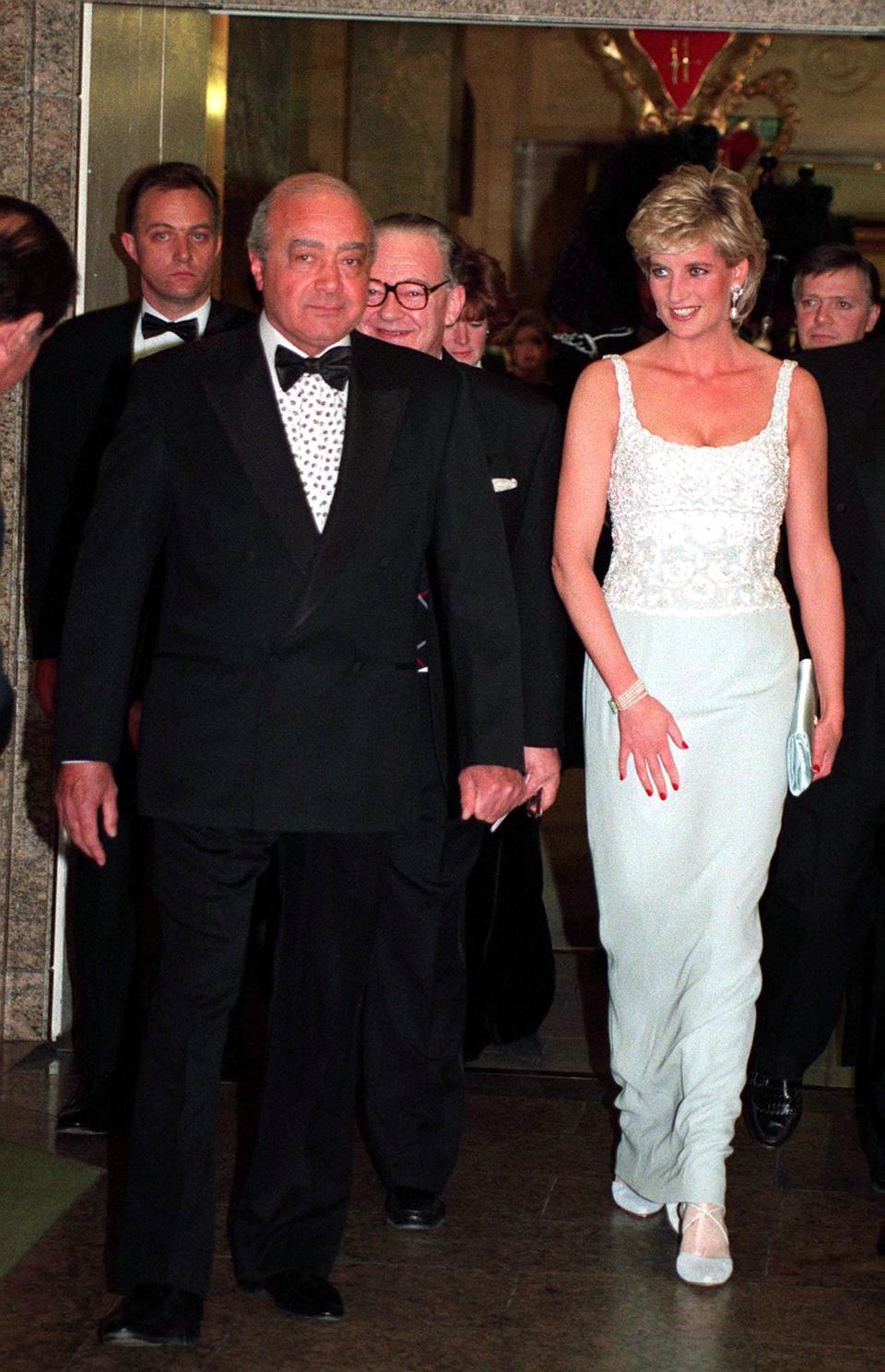

For years, Al Fayed had forged a close relationship with the late Princess of Wales and he was eager to make a match between her and his eldest son. Al Fayed and Diana were involved with the same charities, attended similar events, and their relationship was depicted in dramatic detail during several episodes of “The Crown.”

Al Fayed’s ambitions of proving a royal conspiracy came crashing down in 2008 when the jury at the official inquest into the deaths of Dodi and Diana decided that they had been unlawfully killed.

The jury pinned the blame on the couple’s chauffeur, Henri Paul, who was driving under the influence of alcohol, and on the paparazzi that pursued the couple on motorbikes from The Ritz in Paris into the tunnel where their car crashed.

He responded to the deaths by turning Harrods into a shrine to Dodi and Princess Diana.

Following the accident he dressed the windows of Harrods in black, and would continue to do so every year on the anniversary of Dodi’s and Diana’s deaths.

Two memorials to the late couple used to be on show at the store — a bronze statue of the couple dancing, which stood near to one of the store’s entrances, and an area on the lower ground floor showcasing photos of the couple, and some of their possessions, surrounded by candles.

The statue was returned to Al Fayed in 2018 and the memorial has been dismantled.

“We are very proud to have played our role in celebrating the lives of Diana, Princess of Wales and Dodi Al Fayed at Harrods and to have welcomed people from around the world to visit the memorial for the past 20 years,” Michael Ward, Harrods managing director, said at the time.

“With the announcement of the new official memorial statue to Diana, Princess of Wales at Kensington Palace, we feel that the time is right to return this memorial to Mr. Al Fayed and for the public to be invited to pay their respects at the palace,” Ward added.

Al Fayed could be very generous, making big donations via his family’s charitable foundation to places such as Great Ormond Street and Royal Marsden hospitals. Al Fayed also made quiet payments for private medical care for certain employees who were ill.

A starring role in a few episodes of “The Crown” wasn’t Al Fayed’s only brush with the film industry.

In 1979, he set up film production company Allied Stars Ltd., appointing Dodi as CEO. The company backed the film “Chariots of Fire,” and it earned them four Academy Awards for Best Picture, Original Screenplay, Costume Design and Original Score.

Al Fayed also funded Keith Allen’s 2011 documentary “Unlawful Killing,” based on the death of Princess Diana, which Allied Stars produced. The production company is now defunct.

Due to Al Fayed’s prickly relationship with the British establishment and the royal family, Harrods lost its long-held royal warrants in 2000. Al Fayed removed them and replaced them with an Arab crest.

During King Charles III’s coronation earlier this year, Harrods did not do anything special beyond issuing a special blend of English breakfast tea and Scottish shortbread fingers, both in decorative tins.

Al Fayed is survived by his Finnish wife Heini Wathén, their four children Jasmine, Karim, Camilla and Omar, and numerous grandchildren.

— With contributions from Joelle Diderich, Paris

Best of WWD

Solve the daily Crossword