Find The Most Perfect Sandwich In The World In New Orleans

Elsewhere in this old city, the racket, the ruckus, is already being raised. By 3 p.m., tourists are listing along Bourbon Street, hollering just to be hollering, lost in the euphoria of their second fruity hurricane. Bands—Dixieland, zydeco, more—are tuning up, the music washing out the doors of the bars and into the fading sunlight. By 3:30 p.m., the rotating bar at Hotel Monteleone is already jammed; the din growing with every spin and every Sazerac, Southern Comfort, and brown glass of Jim Beam. Slot machines tinkle at the casino; cash registers ring at the souvenir shops on Canal.

Cedric Angeles Fryers at work in Domilise's Kitchen

Cedric Angeles

But not here, not on Annunciation Street. Here, in this humble place with the hand-painted sign, the loudest sound you hear is the hiss and roil of the deep-fat fryer, as the ladies at Domilise's Po-Boy and Bar drop in another handful of shrimp and oysters and slather another log of crusty French bread with mayonnaise. The radio is turned low, the Allman Brothers singing about cheating women, wasted time, and moving on. The people crowded into the five small tables do not talk much. They mostly just chew, and sigh.

The lunch rush, some days interminable, has ebbed to this. You might stand in line for a good po'boy, but you should never, ever rush in the eating of one.

"This is my first shrimp po'boy," says Sylvia Villanueva, who is here to work on a construction project at the city's airport. "I guess I don't have to go anywhere else," she says, and it is unclear if she means here, New Orleans, or in the whole wide world.

"It was delicious," she says.

People always want to know the secret to it, as if it were some kind of dark magic.

Cedric Angeles Domilise's Po-Boys and Bar owner Joanne Domilise (center) with members of her team.

Cedric Angeles

"When no one is looking, we run across the road to the river and get a big bucket of river water, and before we make one, we slosh it all over it," says Debra Parker, smiling, as she closes a loaf of the New Orleans-style French bread around a mound of fried shrimp and oysters.

I do not believe this is true, but I do not think anyone would care.

Elsewhere, in cities safely above sea level, where a Friday lunch does not last three and a half hours and a hangover is not considered a valid medical excuse, a sandwich may be nothing much, merely a thing you grab on your way to something more important. Here, the po'boy is a symbolic dish, one of the signature dishes of New Orleans. It got its name in hard times 89 years ago, in a season of burning streetcars and flying bricks. But, like so many things here, it has morphed into a kind of celebration.

Cedric Angeles Make a date at Mother's and enjoy the company of the friendly staff.

Cedric Angeles

"Po'boys give you New Orleans on a piece of paper," says JoAnn Clevenger. Her Upperline Restaurant has been called one of the best fine-dining experiences in the city. They don't do po'boys at Upperline, but here in New Orleans, it's routine to see world-class restaurateurs and renowned chefs hunched over still-warm takeout po'boys as they plan wine lists and haute cuisine. "The excitement of our food and our city, wrapped in paper, a po'boy is much better than a sandwich. It's a kind of celebration, to unwrap that paper and take that first bite. Rich, poor, it's the same. It satisfies. There is a sense of community in it, of sharing. "I'll give you a bite of mine if you'll give me a bite of yours." Just sitting there, together, getting kind of messy…" she says, laughing out loud.

Cedric Angeles Guy's Po-Boys' owner Marvin Matherne

Cedric Angeles

At 2 p.m. on a weekday, Marvin Matherne is still taking orders from behind the counter at Guy's Po-Boys on Magazine Street, still stuffing that crusty bread with crisp oysters, breaded pork chops, hot sausage, and layers of cold ham and cheese.

"I'd say I've made about 850,000 of "em, and that's on the low side," he says, but that is just a guess. "That's a lot for one lifetime. Seems like there ought to be more to it than that."

But the further back he goes, the more he remembers; it seems that a lifetime of po'boys is not a bad legacy to have in a city that celebrates the sandwich over most food, and food over almost everything.

The po'boy was an event back when he was a boy, says Matherne, who has owned Guy's for 23 years. "I've lived my whole life here—here and in Chalmette, Louisiana. When I was 7, I used to ride with my grandpa to collect rent. We'd go to my Great-Aunt Tina Messina's place in the Warehouse District and get a po'boy and ice-cold Coca-Cola, and—oh, man…. My grandpa always got ham, so I did too. I think they cut every slice off a baked ham," he says. That was in the 1960s. He says it's odd that he's seldom had a Coke so cold again.

"Not everyone had a car," says Matherne. "They lived and ate in their neighborhoods, and everybody had their own favorite po'boy place. And they'd fight you over it."

Even now, a regular customer will come into the shop with a reluctant friend who looks guilty, somehow, just being there. "I'm trying to convert him," the steady customer will tell him.

"If people were as passionate about church as their po'boys," says Matherne, "the world might be a better place." But that is asking a lot, on Magazine Street.

WATCH: How to Make Mini Muffulettas

You can get some fine gumbo in Mississippi, world-class beignets on Mobile Bay, and even fresh oysters in Grand Central Terminal. But the po'boy, encased in crusty, chewy, New Orleans-style French bread, filled with everything from catfish to barbecued shrimp, truly belongs to New Orleans, from the Marigny to Lake Pontchartrain, Old Metairie to Mid-City, and the Airline Highway to Algiers. It is as much a tradition here as second-day gumbo, or a Sunday Times-Picayune paper littered with fresh-caught "burled" crabs.

Even standing in line is tradition.

"It doesn't matter if you're the King of England and in a hurry, you still have to wait your turn," says Matherne, who has prepared most of the sandwiches in his shop with his own hands. He used to make them for me, wrapped in white butcher paper, the hot oil from the just-cooked seafood mingling with the mayonnaise and seeping through the bread and on into the paper. I lived here as a young man at the corner of Joseph and Annunciation, where you feel the big freighters nudge into the docks on the other side of Tchoupitoulas Street. My house was just up the street from Domilise's Po-Boy, a few blocks from Guy's, and a stroll—but quicker in a Pontiac—from a half dozen other fine sandwich restaurants. I felt, some days, like I would die from cholesterol, or joy.

My favorite at Guy's was the grilled, cayenne-dusted pork chop. I know many of us—us tourists, carpetbaggers, and interlopers—like to speak of the city in superlatives, because we remain enchanted by it, warts, potholes, world-class termites, and all. But a po'boy done right can make lunch elsewhere just kind of disappointing.

Linda Roussel is New Orleans to her bones. In her accent, you can almost hear the litany of the saints echoing in the hallways at Sacred Heart, and the distant clank and hum of the old streetcar on St. Charles Avenue. As a girl, she used to get her po'boys through the back entrance at Ye Olde College Inn on South Carrollton Avenue, as if anything that good almost had to be illegal.

Cedric Angeles Po'Boys being made at Ye Olde College Inn

Cedric Angeles

"It's hard to say who has the best now," she says, rattling off names like Parasol's Bar and Restaurant in the Irish Channel, the classic Parkway Bakery and Tavern, Domilise's in Uptown, Mother's Restaurant on Poydras Street, Guy's, and more. But she believes there is one quality all po'boys must have to be elevated to a place among the city's best: "The sloppier it is, the more gravy and mayonnaise that runs down your arm…that's a good po'boy. And the debris po'boy—you've got to get one with the debris."

Cedric Angeles Enjoy a meaty sandwich at Mother's Restaurant

Cedric Angeles

Debris, like the kind scraped from the bottom of the roasting pan at Mother's, is the detritus that falls from the drippings, usually served with a little (well, a lot) of brown gravy. Some people, she says, like it covered in hot-to-the-touch french fries, then dressed in lettuce, tomato, and mayo.

Sandwich lovers elsewhere might fight you about the po'boy's supremacy over corned beef in New York, or cheese steaks in Philly. But the po'boy, at least, belongs in that company. "Shoulder to shoulder," says Justin Nystrom, director of the Center for the Study of New Orleans and associate professor of history at Loyola University. And like those landmark sandwiches, it has been more than a delicacy. "It's imbued with our history," says Nystrom, "and our culture." To get to the beginning, you have to hail a streetcar.

The name po'boy dates to 1929, but the origins go deeper, historians believe, to the 19th and early 20th centuries, to the birth of jazz. The city's legendary jazz musicians—and dockworkers and others who lingered late in the corner bars to hear them play—would order a hearty sandwich on a French loaf that was called a "peacemaker," maybe because it was offered as a peace offering to angry wives when their husbands stumbled home in the late night or early morning, or maybe because the bread was as long as the famous Buntline Special revolver carried by Wyatt Earp.

"The peacemaker was the predecessor of the po'boy, if not the parent," says Nystrom. Louis Armstrong loved them.

But the popular name "po'boy" will be forever linked to another New Orleans icon. The steel rails of the streetcar still run through the spiritual heart of the city, and it remains the way some people get to work. It's hard to look at the old-fashioned contraption, like a potbelly stove on wheels, and not know absolutely where you are—and smile.

It was different in 1929, just before the start of the Great Depression. The streetcar lines, more extensive then, helped move the city. In July of that year, contract negotiations between the transit-workers' union and the streetcar company broke down, and some 1,000 conductors, motormen, and others walked off the job. The company hired strikebreakers, but union men blocked the rails with debris, tore up tracks, and derailed and burned one streetcar at the foot of Canal Street; they would destroy five more. Two strikers would be killed in the violence that followed.

Cedric Angeles The exterior of Parkway Bakery and Tavern

Cedric Angeles

Bennie and Clovis Martin, two brothers from Raceland, Louisiana, backed the union. They had come to New Orleans to work as motormen in the early 20th century but in 1922 opened a coffee shop in the French Market. As the strike raged, they sent a letter to the union saying they would feed the strikers for free. They stuffed long loaves of fresh-baked French bread from the historic John Gendusa Bakery with simple ingredients like fried potatoes, gravy, lettuce, and tomato. And every time a hungry striker came to the door, as the legend goes, someone would yell out: "Here comes another poor boy."

The strike passed into history; the po'boy never did. It became sustenance for the dockworkers, the muscle that once ran this port city. "Hired and fired every day," says Nystrom of the bare-knuckle life of the dockworkers, who needed a hearty sandwich, from somewhere close by, to get them through a workday that lasted as long as it took to unload a ship by hand. It needed to be portable, and, because this is New Orleans, it had to taste good. Sold in corner shops and bars along the docks and stuffed with meat, cheese, potatoes, gravy, and seafood, it was a staple, till the dockworkers themselves largely faded into the city's past.

Cedric Angeles

Tourism became the modern muscle that made New Orleans go, and the po'boy fueled it too. Over time, it morphed into a more lustrous—and expensive—sandwich, overfilled with savory fried seafood, alligator, layer after layer of roast beef or ham or both, and other good things, and it would never become dainty (though, as a concession to appetite, you can order "a half"). A po'boy does not have to be monstrous to be good but should be at least as thick as your forearm and should—mostly—hold together inside the French loaf. Still, if your shirt is pristine when you're through, then it probably wasn't made right.

"The filling got bigger than the bread," says Clevenger.

But the bread remains the key element. People in New Orleans are snobs about bread. Their po'boy bread is not just crumbs and air.

"It has a thin, crisp crust, and it has chewiness, but not thickness, somehow," says Clevenger.

"Po'boy bread is so unique," says Nystrom, a baker himself. "There is something about baking at sea level, I'm convinced, that makes it…"

Cedric Angeles Zimmer's Shrimp Po'Boy

Cedric Angeles

But you have to eat it the day it's made, he says, or it is "crumbly, like balsa wood." His favorite is the fried shrimp po'boy, dressed, at Zimmer's Seafood in Gentilly, made on bread from the venerated John Gendusa Bakery, studded with sesame seeds.

Cedric Angeles

Cedric Angeles

Others here say nothing will do but the bread from the lauded Leidenheimer Baking Company, which dates to the 1800s. Domilise's and many others will use only Leidenheimer bread.

Everything else seems open to discussion. People here even disagree about the po'boy's heyday, argue whether it has come and gone, or if it is happening right now. Some older people here say it's all gone downhill since fresh-fried trout became so hard to find; that, they say, was the greatest po'boy ever made, just fresh-fried trout on a slightly buttered, barely toasted loaf. They lament the beloved "pepper wiener," which has vanished from butcher shops over time.

Cedric Angeles Liuzza's signature Po'Boy

Cedric Angeles

Some say that the best po'boy of the modern era is the barbecued shrimp version found at Liuzza's by the Track, where the French bread is soaked with the spicy, buttery nectar the shrimp are cooked in. Others say it is the dripping, gravy-smothered roast beef at the famous Parkway. Others, of adventurous spirit, get roast beef po'boys augmented with fried shrimp, covered in beef gravy, and dressed. I think this is showing off.

In such variety, things were bound to get squirrelly. The hipsters like them with radishes, carrots, and cucumbers, but then I try not to think about it.

To some, maybe, it's just one more thing New Orleanians take to excess. But that's their prerogative. "If it has gravy," says Clevenger, "you may just go light on the mayo."

Cedric Angeles Bartender outside Parasol's

Cedric Angeles

Some po'boy restaurants were so dear, so coveted, we dared not even speak their names. I knew writers in New Orleans who refused to write about their most beloved po'boy place, fearful that the outside world would come crashing in. But that secret was never much of a secret, anyway.

Domilise's in Uptown remains, the standard for many folks. Floods recede, time passes, beloved figureheads fade from behind its counter, and it remains iconic and delicious. People who say change is good have never had a half-shrimp, half-oyster po'boy here, the crust of the seafood still hot to the touch, next to a cold bottle of root beer. One recent Loyola University graduate, who stood in line so long and so often it is a wonder they did not hang a sign on him, called them simply "a work of art." Dot Domilise made one for me with her own hands, some 30 years ago. I think that makes me somebody.

A priest said a Mass for her at the Church of St. Henry on General Pershing Street, in the summer of 2013. But people here know her sweet spirit never left the corner of Annunciation and Bellecastle. She owned and ran the po'boy shop and bar for over seven decades, first with her husband, Sam, then with others of her name; it remains in the family. She knew customers by name, and by their orders; she prayed at their gravesides. She is famous for her craft in some faraway places, but she is known here.

People here knew not to come on Thursday, says Parker, ""cause that's when Miss Dot got her hair done."

To this day, if you see a man shuffling down Annunciation with a tomato in his hand, it is likely because of Dot. She did not believe that she could consistently find good tomatoes in the city for her sandwiches and banned them.

"People knew that if they wanted a tomato, they had to bring their own," says Mary Lou Borne, who has worked at Domilise's for 13 years. "People bring "em in and cut slices and offer them to the other people," she says, like it was their own home, their own kitchen. How the place could still somehow feel like that, with a line that routinely snakes out the door and sometimes down the block, is just part of the magic of it. Dot's other standards, and traditions, remain.

"I make sandwiches. I make the magic," says Borne, proudly, when asked what she does at the restaurant, though the alchemy is really just a combination of "top-quality products and top-notch ingredients, fresh…. We don't drop the shrimp into the fryer till you order your sandwich."

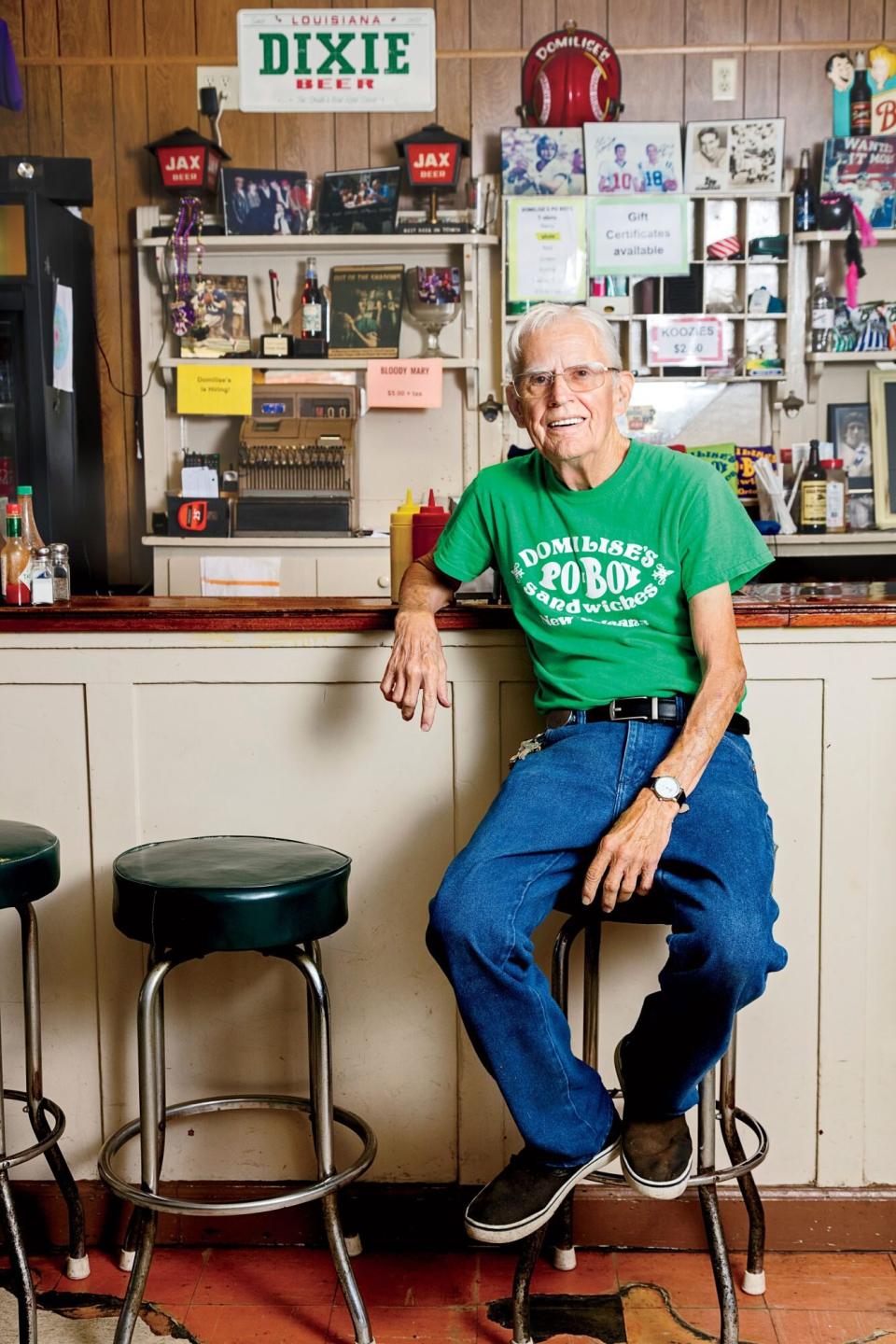

Cedric Angeles Raymond Chauvin has been working at Domilise's for 49 years.

Cedric Angeles

Like almost every other great po'boy place in New Orleans, it seems like there is a lifetime connection between the people and their po'boys. Borne grew up just a few blocks away, on Laurel between Joseph and Arabella. She ate po'boys from Domilise's as a little girl. "My favorite po'boy is the catfish," she says.

Two years ago, the restaurant added a commercial fryer and a grill, and this caused the menu to change slightly. "Customers can get french fries now and a hamburger," but do not go crazy and ask for something like a tomato, Borne says. Instead, here the cooks add a ladle of ketchup-based red sauce to their seafood po'boys, which mingles with the cool lettuce and mayonnaise to create…well, legend.

You still have to order your sandwich at the counter and your drink over at the bar, for no better reason than it has always been done that way. The dining room is still tiny; some customers say this decision is on purpose, or else the whole world really would descend on Domilise's, and the line would probably extend until the end of time.