Mrs. Caroline Astor Was the Ultimate New York Socialite

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

On HBO's The Gilded Age, the family rivalries might be fictional, but the hovering presence of social arbiter par excellence Caroline Astor—played on the series by Donna Murphy—comes straight out of 19th-century New York social diaries.

Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor, known as “The Mrs. Astor,” reigned supreme in New York society to the extent that her annual social schedule was broadly publicized. In winter she entertained at her mansion on Fifth Avenue, hosting teas, receptions, and most lavishly, late-night dinners. The highlight of the season was her annual ball, always in January on a Monday night; dinner at 11 p.m. and dancing until dawn. Early spring called her to England and France (she spoke the language); summer was spent in Newport, Rhode Island.

Caroline descended from the Schermerhorns and the Van Cortlandts, Dutch families that were among the earliest settlers in colonial North America. Considered “old money,” they had earned their fortunes through mercantile businesses and real estate holdings. Nouveau-riche families strove to achieve their acceptance, and famously fueled the envy of such newcomers to New York society as Alva Smith Vanderbilt from Mobile, Alabama. One reporter referred to her maiden name: “plain Miss Smith, mind you.” A social snub by Caroline Astor could sting for years, and the Vanderbilts were infamously on the receiving end.

In 1895, The Redwood Gazette wrote, “Below the surface there are surprises, occasioned by the presence of some one unexpected, some one who has gained prestige by her presence at Mrs. Astor’s ball. And matrons may pass before Mrs. Astor, never knowing that the courteous hostess was well aware of their efforts, even scheming, to procure for some climber the coveted card.”

As leader of society, Astor’s possessions and personal preferences were continuously gossiped and reported upon. Her precious stomacher of diamonds was believed to have once been worn by Marie Antoinette. Her favorite fragrance was a “sweet odor somewhat like wild lavender and garden roses mixed.”

In 1905, Town & Country reported that “Mrs. Astor wore her wonderful emeralds, set off by a profusion of diamonds. Her gown of black, lightened up in the front by a little white, was one of the handsomest that she has worn this season.”

Caroline’s standing had been solidified when in 1853 she married William Backhouse Astor Jr., an investor in real estate and railroads and a descendant of the first Astor to come to America, fur trader John Jacob Astor. Despite Caroline’s husband’s penchant for spending more time on his yachts than with his wife, the couple had five children together: four daughters and one son. In birth order, they are Emily Astor, Helen Schermerhorn Astor, Charlotte Augusta Astor, Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, and John Jacob Astor. Through their marriages—their weddings were the darlings of the mainstream and tabloid press each time—the string of well-to-do surnames associated with the family grew longer. Not only were they a Who’s Who of society, but also a What’s What of New York landmarks; the names Astor, Schermerhorn, and Roosevelt are familiar today on street signs, monuments, and university buildings.

Emily, the eldest daughter, married James John Van Alen in 1876. They divided their time between England and Newport, before her premature death in 1881. The next sister, Helen, commissioned a white satin dress with orange blossoms and old Belgian lace from the elite House of Worth in Paris for her wedding with James R. Roosevelt, half-brother of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, at Grace Church in downtown New York in 1878. Their sister Charlotte married lawyer James Coleman Drayton in 1879; they divorced in 1894 and two years later she wedded the Englishman George Ogilvy Haig in London.

By far the two most luminous and best remembered of the Astor children were the youngest: Caroline (known as Carrie) and John Jacob IV. Carrie lived into her late eighties, having accompanied and co-hosted events with her mother, and continuing the latter’s legacy after her death in 1908. John Jacob lived extravagantly, married illustriously (twice), and died tragically on the RMS Titanic. Tall, slim, and mustached, he caught the eye of portraitists, photographers, and caricaturists alike.

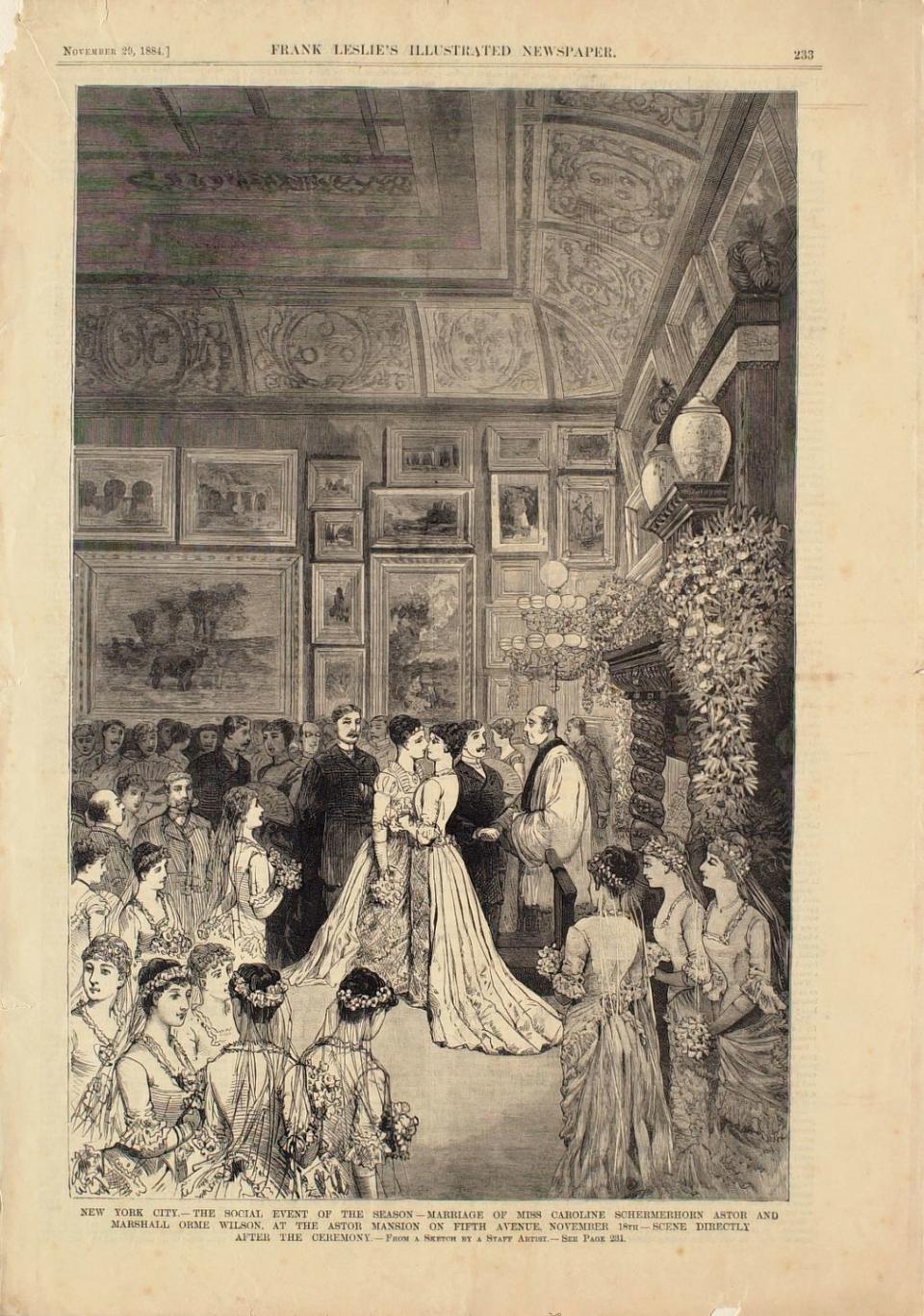

The favorite daughter, Carrie, was described by one popular magazine as the “‘beauty’ of the house of Astor.” She debuted in society and as a teenager took a liking to banker Marshall Orme Wilson, who hailed from a family that her parents deemed arriviste. Carrie persisted, and the marriage was eventually allowed. She wed Wilson in November 1884 among her family’s art collection (they preferred French Romantic landscapes—Jean Corot and Jules Joseph Lefebvre, to name just two) in their home at 350 Fifth Avenue. This was her parents' brownstone, replete with art gallery, ballroom, and the imprimatur of architect Stanford White, who had redesigned the interior in 1879. It was the site of extravagant balls to which only the approved Four Hundred, as determined by her mother and society gadfly Ward McAllister, could attend. (When McAllister died in 1895, the amiable and popular Harry Lehr took his place alongside Astor.) Her mother infamously chose to leave the home and build a new mansion uptown (840 Fifth Avenue at 65th Street; completed in 1896), motivated in part by her disdain for the forthcoming Waldorf Hotel to be built by her nephew William Waldorf Astor, a commercial enterprise situated distastefully close to her home. In February 1896, she threw a housewarming ball for 600 guests, greeting each one of them while standing beneath her portrait by French society painter Charles Carolus-Duran. Outdoors it was a frigid New York evening. At Caroline’s, guests danced among American Beauty roses and imported tropical plants (she would donate them the next day to nearby hospitals).

Carrie and Marshall’s two sons, Marshall Orme Wilson Jr. and Richard Thornton Wilson III, stewarded the Astors’ reputation and fame well into the 20th century. Among other philanthropic efforts, they donated couture gowns by the Houses of Félix, Doucet, Worth, and Paquin, and exquisite works of porcelain to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

John Jacob Astor IV, only son of Caroline and William Backhouse Astor Jr., followed societal expectations, attending Harvard University, becoming a colonel in the U.S. Army, and managing the Astor’s real estate fortune. He eventually built the Astoria Hotel, which would merge with his cousin’s Waldorf Hotel in 1897. In 1889, Frank Leslie’s Weekly described the bachelor as “naturally a very big fish in the matrimonial sea, and many an aspiring and devoted mother has angled for him with fruitless but eager anxiety.” His marriage to Ava Lowle Willing in 1891 was the talk of two towns: New York and Philadelphia, from where the socialite hailed. The fashionable, oft-photographed Willing commissioned from the House of Worth a wedding gown of “rich, heavy, creamy duchesse satin with an immense train” for herself, and for the bridesmaids, “Marie Antoinette gowns of pink chiffon.” Mother-of-the groom, Caroline Astor, wore an embroidered, deep violet satin gown and matching capote with violet-tinted ostrich feathers.

The couple moved into their section of the French Renaissance chateau–style adjoining houses at 840 Fifth Avenue. Their two children were Vincent Astor (he would marry Roberta Brooke Russell in 1953; known as Brooke Astor, she was the next “The Mrs. Astor” and a great philanthropist) and Ava Alice Muriel Astor. Yet again, however, the marriage was better arranged on paper, and unhappiness led the two to divorce in 1910. Soon after, John Jacob, by then in his late forties, married the eighteen-year-old Madeleine Talmadge Force Dick, who would survive the RMS Titanic disaster along with her in-utero son, to be named John Jacob Astor VI. John Jacob Astor IV died in the sinking of the ship. Willing remarried in 1919, to the 4th Baron Ribblesdale, granting her the title Lady Ribblesdale, and remaining a star subject (along with her companion lapdogs) of society photographers.

Today, the Astors' presence continues, from the flowers in the Great Hall of The Metropolitan Museum of Art that Brooke Astor funded in perpetuity (the arrangements are changed weekly), to the grounds of Merriscourt, Thomas Astor's home in the Cotwolds, now a venue for bespoke weddings. The Gilded Age might be over, but their family name is still as powerful as ever.

You Might Also Like