How Naming Rights Became the Art World's Most Controversial Issue

Sarah Arison could have engraved her name on almost anything she wanted at a new 40,000-square-foot nonprofit arts complex in New Haven, Connecticut—but she turned down every offer.

Arison wanted to help raise $15 million for NXTHVN (pronounced “Next Haven”), a creative incubator in the shadow of Yale’s steeples, because she believed in its mission to foster the careers of artists and curators of color. However, when she pledged $600,000 to fund a 60-seat black box theater over three years, she suggested the organization offer the naming rights to someone else.

“I was happy to give the organization the opportunity to use those naming rights for continued fundraising with another donor who might be motivated by that,” says Arison, an heir to the Carnival Cruise Line fortune, president of the $422 million Arison Arts Foundation, and a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art.

Traditionally, naming rights have been viewed by the rich and civic-minded as a way to imprint their names on history while helping the organizations they support to build endowments, acquire masterpieces, and undertake ambitious expansion plans. But in recent years the names on the walls of major institutions have come into focus—and increasingly under scrutiny.

Arison isn’t alone in rejecting naming opportunities. NXTHVN has raised nearly $5 million, but not a single donor has asked to have his or her name placed on its available and eminently nameable spaces, including studios, apartments, offices, a terrace, and a café. “It’s unlike any other campaign I’ve run,” says Rodney Franks, a fundraising consultant who has been in the field for more than 25 years. What’s happening at this nonprofit (co-founded by art star Titus Kaphar) could be a sign that the conversation around naming rights, which were once seen as an unparalleled status symbol, is changing.

America’s most prominent people have been slapping their names on university libraries, museums, and hospital wings for generations, but as wealth exploded globally over the past two decades, the chance to buy a bit of immortality turned into a competitive sport.

Billionaires David Geffen, David H. Koch, and Stephen Schwarzman clamored to inscribe their names on buildings, galleries, and plazas at the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the New York Public Library. Chicago is home to the Kenneth C. Griffin Museum of Science and Industry, and in Los Angeles the soon-to-open Academy Museum of Motion Pictures will have the Dolby Family Terrace, the Barbra Streisand Bridge, and the Saban Building, named for philanthropists Haim and Cheryl in gratitude for a $50 million gift. Even restrooms are hot commodities; at the New Museum, four public bathrooms are named after Jerome L. Stern, the venture capitalist who died in 2017 but had made a six-figure gift a decade earlier.

But amid the coronavirus pandemic and social justice protests, some patrons have begun to think twice about displaying their largesse, while others have found themselves in a position—you might call it “canceled”—where their name does more harm than good. Being credited as “Anonymous,” once a sign of WASPy humility, may start to seem like a safe bet in an era when donors are publicly pilloried by artists and armchair critics for their politics, social scandals, and business practices.

In March billionaire Leon Black announced that he would step down as chairman of the board of trustees at MoMA, which had named its film center for Black and his wife Debra after they made a $40 million donation in 2018. Black had received critical attention related to his ties to Jeffrey Epstein, the late financier and convicted sex offender; he also stepped down as CEO of private equity giant Apollo Global Management after it was revealed that he had paid Epstein $158 million for tax and estate advice in 2008 following Epstein’s conviction for soliciting a minor. A spokeswoman for MoMA—which has also been asked to remove the late architect Philip Johnson’s name from spaces due to allegations of racism—didn’t respond to requests seeking comment.

“I bet the amount Black has given is vast,” says a trustee of another New York museum who asked not to be named. “What do you do if you’re on that board? What’s the best thing for the museum? I’m glad I’m not sitting in those discussions.”

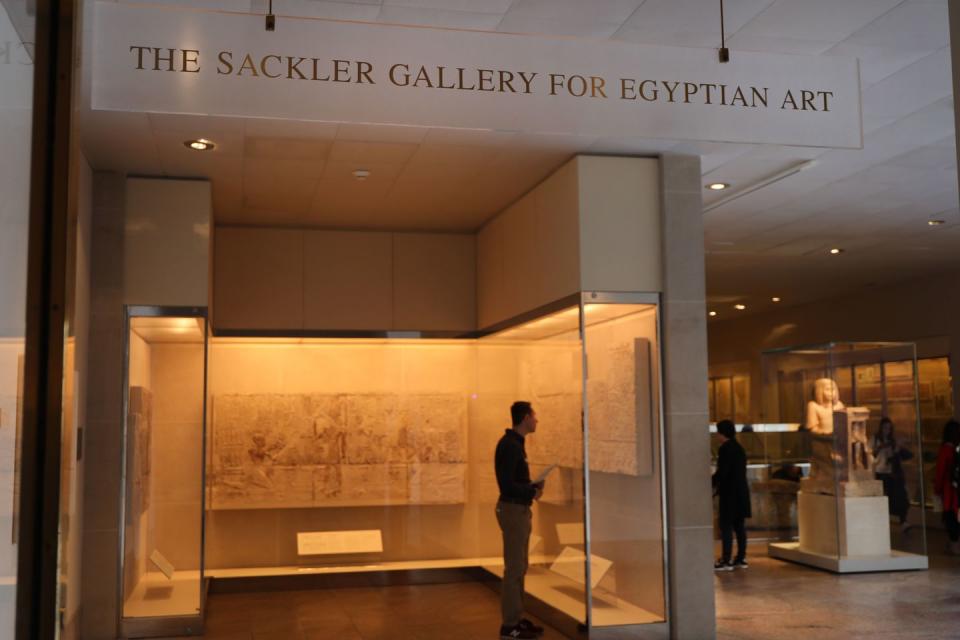

Black isn’t the only one facing criticism. Protests against the Sackler family, one of the largest benefactors of museums in the U.S. and Europe, have roiled the art world in recent years in the wake of revelations about the family’s role in the opioid crisis. Two years ago the Louvre removed the Sackler name from one building, and many museums, including the Tate and the National Portrait Gallery in London, have pledged to stop accepting gifts from the family. The Met is reviewing whether to remove the Sackler name from the wing that houses the Temple of Dendur, and London’s Serpentine Galleries removed the Sackler name from its website for future exhibitions, saying it was part of a rebranding campaign in which the Serpentine Sackler Gallery will now be known as the Serpentine North Gallery.

This trend is not something every member of the Sackler family—which has multiple branches with varying degrees of involvement in the pharmaceutical business—agrees with. In 2019, after Tufts University removed the Sackler name from five of its facilities, Jillian Sackler, the widow of Arthur M. Sackler, said in a statement, “The man has been dead for 32 years… None of his philanthropic gifts were in any way connected to opioids or to deceptive medical marketing.”

Some insiders worry that this intensified scrutiny of donors will have a chilling effect at a time when cultural institutions desperately need funding. In times of crisis, says Adrian Ellis, founder of AEA Consulting, which specializes in strategic and operational planning in the cultural sector, “parading one’s wealth can be seen as bad taste… You may want to keep your head down.”

Fittingly, over the past year some patrons have declined not only naming opportunities but even public announcements of their gifts. “There was reluctance to announce capital gifts with names associated with them because of the environment,” says David Resnicow, president of Resnicow and Associates, which advises cultural institutions on communications and strategic planning. “It would feel wrong to announce a big gift when everything has shut down.”

Private contributions accounted for about a third of the revenue of U.S. museums before the pandemic, according to a 2018 report by the Association of Art Museum Directors. In recent months, patrons rallied to ensure that their pet causes survived, but in less visible ways. Capital campaigns were put on a back burner as institutional priorities shifted. Operating needs, which don’t involve drumbeating, came front and center.

Of course, naming rights aren’t entirely about ego. “Donors are absolutely the pillars of private institutions, and we have to be welcoming to them, particularly in the U.S.,” says Richard Armstrong, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Social recognition has fueled philanthropy for centuries, which is why offering naming rights has been one of the most powerful fundraising tools. Not only does it acknowledge a donor’s generosity, it inspires others to give.

Naming is also a step toward “a kind of immortality,” says Tom Finkelpearl, former director of the Queens Museum, who served as commissioner of the New York Department of Cultural Affairs from 2014 to 2020. “David Koch is dead, but you see his name all over the city.” The New York State Theater at Lincoln Center was renamed for Koch, the oil and gas billionaire, after a $100 million gift in 2008. In 2014 the Metropolitan Museum of Art named its Fifth Avenue plaza after Koch following a $65 million gift. In 2015 Koch gave $150 million to New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to build a 23-story facility bearing his name.

What would be the impact on such large gifts if donors start to wonder whether having their name on a gallery were an invitation to hammering them on social media? “It’s likely to have a chilling effect on philanthropy,” Ellis says. “If they fear rough justice, they may reconsider their philanthropic agendas.”

Museum trustees say naming rights aren’t likely to go away completely. In November 2020 the Baltimore Museum of Art said it would name two public bathrooms after filmmaker John Waters, in recognition of his gift of 372 works of art, including pieces by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. But while Waters, who is known lovingly as the Pope of Trash, seems an unlikely candidate for cancellation, not every donor is so lucky.

In the summer of 2019, Warren Kanders stepped down from the board of the Whitney Museum of American Art after months of protests by activists, artists, and staffers against his company Safariland, which manufactures tear gas as well as military and police equipment. “That was such a terrible situation,” says a Whitney trustee who asked not to be named. “And yet there’s a great exhibition that’s going to happen because of him.”

Indeed, when the museum was discussing the feasibility of Day’s End, an ambitious public art project by David Hammons that opened in May in the Hudson River near the Whitney, Kanders offered the seed money to “study it and see if we can do it,” the trustee says. “This is not who I want to have dinner with, but I love the idea that he said it.’’

A donor’s infractions need not be recent to attract attention. In Missouri the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is reassessing its name after a local newspaper exposed the segregationist activities of its co-founder William Rockhill Nelson, who died in 1915. Now the museum’s board and leadership “are taking a careful and measured look at the museum’s history, including that of our founders,” says a spokeswoman.

Reputational risk is one of the points many institutions are grappling with when it comes to naming rights, asking whether it’s fair to apply today’s values to past behaviors. “The Morgan is such a treasure,” a New York museum board member says about the Morgan Library & Museum, which began as the private library of financier J.P. Morgan. “But were the Morgans above reproach?”

Looking ahead, nonprofits are trying to protect themselves in case a significant donor suddenly falls from grace. Gift acceptance policies now routinely include morality clauses similar to those in celebrity endorsement contracts, and in the art world, where perceptions are everything, such policies could lead to uncomfortable conversations. “No one,” says Thomas C. Danziger, an attorney who specializes in art transactions, “wants to go to the Jeffrey Epstein Wing.”

Museums “understand that it can be off-putting if they say, ‘Please, can I have a million dollars, but if there’s any reason we don’t want to be associated with you, we’d like the right to unilaterally decide to take off your name,’ ” says Diana Wierbicki, partner and global head of art law at Withers Bergman LLP.

Adam Levine, director of the Toledo Museum of Art, says that such conversations don’t have to be tricky. “In my experience, those who want to support an institution do so because of their love for its purpose,” he says. “And anything that gets in the way of the institution’s ability to achieve its mission should be avoided to the extent possible—even if it includes the reputational risk introduced by a donor.”

One trend is so-called sunset provisions, which set a time limit for naming rights. Currently, attorneys general in 23 states are trying to pave the way for nonprofits to disassociate themselves from the Sackler name without liability, and over the past decade New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs has moved away from approving “in perpetuity” naming rights for the 34 organizations located on city-owned land under its jurisdiction, including the Brooklyn Museum and the American Museum of Natural History. According to a department spokesman, such arrangements “limit long-term fundraising options for public assets and raise other public policy concerns,” which can be understood to mean that what seems like a lot of money today may not seem that way forever.

In 1973, for example, Avery Fisher gave $10.5 million to the main concert hall at Lincoln Center, where his name would be inscribed for the next four decades. Then, in 2014, Lincoln Center decided to resell the naming rights to the hall as part of a $500 million campaign. The Fisher family got $15 million back, and David Geffen stepped forward with a $100 million gift, for which the building was renamed David Geffen Hall in perpetuity. “I have everything I want,” Geffen told the New York Times in 2015. “There’s nothing I’m looking to buy. And I’d rather see it do good while I’m here than give it away when I’m gone.” He got a deal. Across Lincoln Center’s plaza, Koch paid the same amount to have his name on David H. Koch Theater for just 50 years.

A little ways to the south, at MoMA (where Geffen got his name on a new wing and galleries following a $100 million gift in 2016), big donations don’t have a term. Some of the museum’s deep-pocketed donors seem to take solace in the idea that their naming rights are meant to last forever, no matter what they do. “We all are in perpetuity,” says a longtime trustee. “If I found any different, I’d be pissed off.”

This story appears in the Summer 2021 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like