The night Jon Batiste stormed the Grammys, his wife was fighting for her life: they tell their story

“Whooo, yeah!” Jon Batiste whoops. The flamboyant composer and pop star – bright green suit, hair straight out of a Basquiat painting – is one of the most thoughtful, articulate musicians you could ever hope to meet, but he just loves a spontaneous expression of enthusiasm. He and his wife, the writer Suleika Jaouad, are sitting together on a sofa in a London hotel. Two days earlier, they celebrated Batiste’s 37th birthday with the news that he had been nominated for six Grammys, including: Album of the Year, for his genre-spanning World Music Radio; Record of the Year, for the feel-good dancefloor shaker Worship; and Song of the Year, for the heartfelt ballad Butterfly.

“What a great day,” Batiste says, his voice retaining the laidback flavour of his native New Orleans, despite studying piano in New York at Juilliard followed by a seven-year stint as the band leader on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.

On the satirical US chat show, he emerged as an engaging personality and multi-talented musician, sharing a piano stool with Stevie Wonder, jamming with Dua Lipa in a lift, and trading keyboard licks with Kermit the Frog. Under the radar, meanwhile, his recording career was taking off. Last year, Batiste walked off with the Grammys’ biggest prize, Best Album, for his stirring paean to black American music, We Are, beating off competition from Taylor Swift, Kanye West and Lady Gaga. It joined a growing collection of trophies that also includes an Oscar for the soundtrack to the 2020 Pixar musical Soul.

This year, Batiste finds himself in competition with Swift again, although he prefers to see it as a shared celebration. “I’m a Swifty,” he says with a grin. “I didn’t come across Taylor during those years on the TV show,” he adds, but since he left in August last year, “we’ve corresponded back and forth”.

On the song Butterfly, though, hangs a story. We’re in Soho to talk about the Netflix documentary American Symphony, shot by acclaimed director Matthew Heineman. Over his career, the 39-year-old has regularly put himself in the way of danger to make compelling verité films, from the Oscar-nominated Cartel Land (2015), about vigilante groups either side of the US-Mexico border, to Retrograde (2022), about the panicked American retreat from Afghanistan.

Batiste had scored Heineman’s 2020 film The First Wave, shot inside a hospital in Queens as the Covid-19 pandemic hit, and was looking forward to his next project – “building an unprecedented symphonic orchestra to play an unprecedented symphonic work” – when it occurred to him that Heineman could document its creation. In American Symphony, Heineman set out to follow Batiste as he prepared a piece that, when premiered at New York’s Carnegie Hall, would “break open the doors” of the symphonic tradition. The filmmaker knew it would be no easy task. “It’s hard to capture the process of creativity,” he says.

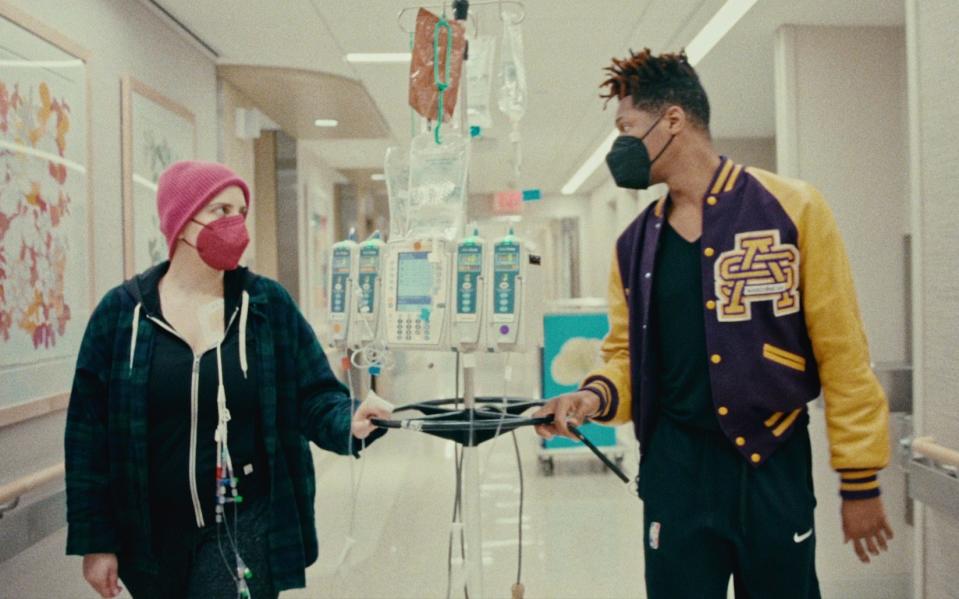

Then came the bombshell that would change the course of the film. “A month into us deciding to do that project,” Batiste recalls, “everything shifted.” Jaouad learned that the leukaemia that she had overcome in her early 20s had returned. Rather than abort the documentary, she and Batiste decided to “braid together” the original narrative with one he calls “the symphony of life – the duality of ups and downs, tragedy and triumph that exist in everybody’s life”.

It was not a simple decision. “To receive the news of a cancer diagnosis is a kind of implosion of your life, and implosion of the lives of your loved ones,” Jaouad says. “I’m keenly aware that cancer doesn’t just affect the person in the hospital bed. In some ways, I think it can be harder for the people around you.”

A decade earlier, Jaouad had written about her leukaemia in a column for the New York Times, later articulating her experience in a bestselling book, Between Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of a Life Interrupted. Now she faced mortality again. “Suleika was about to embark upon this bone marrow transplant with a very unclear outcome,” Heineman says. “And she didn’t want to be part of the film. It took some deep conversations and trust-building to get her to let me turn the camera on her.”

“It’s not easy to pull back the curtain on your life and to let someone in to any private moment, let alone the really challenging ones,” Jaouad explains. “But we decided we wanted to do it as honestly, as vulnerably, as we could, you know, in this age of Instagram and filters.

“It’s very hard to get a sense of what someone’s life is actually like, especially if they’re in the public eye,” she continues. “So it felt especially important to me, having seen the way illness narratives are often told – as this triumphant arc that ends with survival, and even a sense that you return from the worst moments of your life stronger and better and braver for them – to show what it’s like when you’re really in the trenches, when you don’t know what’s going to happen, when you don’t know how your story is going to end.”

Even so, she notes, “there were so many moments where we wanted to say, go away!” Batiste experienced anxiety and panic attacks, and found it impossible to sleep. Heineman captures him with his head under a pillow talking to his therapist, and speaking to a friend about how all black male artists “crack at a certain level, they all crack” – “I can handle a lot,” he tells me now. “But, even me, at a certain point, I will crack.” Those moments came out of 1,500 hours of filming. “It was 14-hour days, for seven, eight months,” Batiste says. “Leaving the stage with the cameras, going in the dressing room with the cameras, going home with the cameras, the cameras in the hospital rooms, the cameras everywhere.”

“It would have been much easier to put our guard up, to only show certain curated moments, to not take the camera into the belly of the beast,” says Jaouad. “But I believe that when we dare to share our most vulnerable stories, they create a reverberation. And that’s my hope with this film.”

Jaouad and Batiste live in a beautiful apartment in New York – they used to share a two-room flat and Batiste starts to laugh as he remembers the day they knew they needed a bigger place, “Suleika works in quiet, and I’m six, seven in the morning still up listening to music.” They’ve been together for 10 years, and married for two, but were friends long before that after meeting at a summer jazz camp as teenagers. Jaouad plays classical double bass and also studied at Juilliard, where they “reconnected”, and then “orbited in and out of each other’s lives”. Batiste achieved viral fame online, performing for free with his band Stay Human in the streets and on the New York subway, while Jaouad planned to be a war reporter.

“But the first time I got sick at 22,” she says, “when Jon found out, he brought his whole band to the hospital. I’d been an inpatient for about six weeks. And he put on an impromptu concert, right there in my hospital room, which I think is a perfect example of how Jon alchemises darkness and, you know, twists the prism to allow a little light to come in. As the sound of the music flowed out into the hallway, doctors and patients and nurses started to stream out of their rooms and everyone began to sing and to dance together.”

Although American Symphony may seem like a departure from Heineman’s previous work, the director had made a music doc before, The Boy from Medellín (2020), about the Colombian reggaeton singer J Balvin and, he tells me, “in some ways, it feels like all my films have led me to the point of being able to make this film… whether it’s Isis in Syria (City of Ghosts) or the opioid epidemic (The Trade), what I’ve tried to do is to tell very character-driven stories about human beings overcoming obstacles”.

Telling Batiste’s story, that of an artist on the brink of a major breakthrough trying to compose his first symphony, brought all sorts of challenges of its own. “Jon’s life is crazy, you know,” Heineman says, “his schedule is changing 75 times a minute. We were just constantly trying to open doors, including the Grammys… we tried for months through the official channels but didn’t get access – so I snuck in as part of Jon’s entourage.”

“I had to shoot with my iPhone,” he adds. “I stuck out like a sore thumb. But for a film that was so up-close until that point, to not see Jon’s perspective and be there with him would have been so weird, to have to just cut to the [official] feed.”

To witness the sheer energy that Batiste summoned on the night, performing live before a global TV audience, is all the more startling when you’re aware of the crisis that he and Jaouad were facing at the time. “It’s like when Clark Kent takes off the glasses and puts on the cape,” he explains. “It’s a thing that you see many performers do – or anybody who has to go in and get to that level of megawatts in whatever profession. You put your superhero suit on and step forward.”

When the Best Album award was announced, Heineman says, “Jon was sharing a table with John Legend and his family, and I had, like, their kids on my lap as I was trying to film. But none of us expected Jon to walk away with the biggest prize in music. And it was just an amazing moment for him.”

It arrived while Jaouad was in hospital for the transplant – “having watched Jon work toward a moment like this from the time that he was a child, it felt really important to me that he go and do those things and that they not feel at odds with each other,” Jaouad says.

Batiste was aware that Jaouad was being purposefully stoic, and at those moments, he says, he was constantly thinking, “I wonder how she’s really doing.” The very next day after the Grammys, he was back at the hospital – “that’s the kind of stuff that you can’t find equilibrium in”.

Batiste’s American Symphony is a work that aims to expand the accepted classical canon, which he believes has undervalued and disbarred black musical genius.

“I was listening to Duke Ellington today,” he says, “There’s a lot of stuff he did that’s not recognised for what it was.”

Batiste set about reinventing the components that would make up a classical orchestra if it was created in contemporary America rather than arriving in standardised form from 19th century Europe, taking in the continent’s diverse musical traditions and instruments – from Dixieland to hip-hop, mandolin to synthesizer.

In the film, he discusses a “psychosis in how we perceive black entertainers and intellectuals” in a culture where “they have black people cooning and mugging for the camera and smiling and dancing for centuries” – he talks about the act of creating the symphony with the awareness that he is representing his race. I wonder if that’s a heavy weight to carry. It’s not a weight, he says, “All of this is rooted in like, do you know your stuff? Do you actually know what you’re doing?” If the work is strong enough, he believes, it will do the job for you.

It was Batiste’s mother who wanted him to have a grounding in classical music. Yet his talents feel boundless: that the same musician who created World Music Radio performs the minimalist 2020 album Meditations with guitarist Cory Wong is like finding out that Paul Simon and Brian Eno are the same person. World Music Radio goes even wider than American Symphony in terms of the musical forms flowing into it – “It took a lot to put that together,” he says, with feeling.

Batiste is less well known over here, but he intends to put that right; leaving The Late Show means that he can tour here as he couldn’t before. At the same time, as he says in the film, he’s wary of letting his ambition take over, “becoming the primary way that you relate to yourself and to your loved ones”.

How does he square that note of caution with the apparently irresistible momentum of his career? “We talk about that all the time,” he says, turning to Jaouad. “What do you say? I’m over-ambitious?”

“Do I say that?” she replies.

“You said it once before...” He pauses. “It’s a struggle for anyone that’s talented… it’s the struggle of the gifted child. How do you resist it is the question”.

Jaouad, as the film shows, learned that her cancer treatment must be ongoing. For them as a couple, it has brought a change in priorities. “We have been trying to live every day as if it is our first,” she says, “to wake up with a sense of curiosity and wonder.” It has led them to rethink how they use their time. “Taking a month to travel with our dog and our families in Europe is not something we necessarily would have made space for before.” But also to embrace “experimentation” and “the licence to play” in how they create.

And that song Butterfly? Jaouad says that while she was in hospital “we couldn’t be together for the full time because the germ risk was too high. And Jon started composing these lullabies for me each night, one of which became Butterfly.

“So it feels like a real full-circle moment for us to get to be here together, to be celebrating the film, to be celebrating the nomination. And to, hopefully this time around, get to attend the Grammys together.”

Batiste nods happily. “We get to do it as a do-over.”

American Symphony is on Netflix