Normandy or Brittany – which is better?

Bretons and Normans share much. They both live in places with long and often crinkle-cut coastlines, by turns beguiling and savage. Both have a marked taste for shellfish, cider and butter. Boy, do they like butter. A serving of Breton kouign aman cake fulfils your cholesterol needs for a decade.

They have the same colour scheme – grey and green through white and blue, with a constantly changing sky. And both have deep, ambiguous links with the British Isles. In Brittany, it's the early-established Celtic connection, though that didn't stop their corsair ports playing merry hell with our shipping a few centuries on.

Meanwhile, the Norman invasion of England permitted "William the Bastard" to become "the Conqueror". The invasion, of course, went the other way in 1944. Ties with both regions are thus not only historic but also emotional. The D-Day beaches exert an enormous power as, in a quite different register, does the Interceltic Festival at Lorient, where our fringe nations gather with Bretons amid bagpipes and similar.

There are, though, significant differences between the two. Out on the nose of France, Brittany has a sharper identity, thanks to the sea and the swirl of Celtic culture. Despite its Norse background, Normandy is more benign and assimilated. Nor is there a Norman language in which fruitcakes might demand "Free Normandy". So they don't.

Coasts

The Pointe-du-Raz and Pointe-St Mathieu, Brittany's final flings, are where land ends and legends begin. Given the elemental force of rocks, cliffs and turbulent ocean, it's no surprise that Bretons have needed myths to get them through.

Back from this edge, the Brittany coast rarely lets the drama flag. To the north, from the Pays-des-Abers to the Pink Granite Coast, with its hallucinatory rock formations, the wildness thrills children… and parents too, as they try to stop the nippers plunging.

Headland after headland defies sea and sky, overlooking an inner shore littered with rocks and islets, as if someone were crumbling a landscape up above.

The southern coast is neater, with a marginally more gentle littoral – but still unruly enough for those who find the Mediterranean idle. Try the beaches at Concarneau or Vannes, with the island-spattered Morbihan Gulf out in front, and the senses soar. Talking of islands, Brittany has a variety – apparently chipped off the mainland and hurled out to sea – which Normandy cannot match. Farthest west, and most battered, is Ouessant. Sein floats barely above sea level while Batz is where I'll retire to grow organic vegetables and subtropical plants. If they'll have me.

Normandy might not have comparable islands but its Cotentin Peninsula – France's thumb sticking up towards Blighty – has shagginess similar to Brittany's. To the west and north, lanes through tall-hedged farmland suddenly burst out to an infinity of sands with edges rising high, rocky and rugged. Stand on the Nez-de-Jobourg, culminating point of the Cap-de-la-Hague 420 feet above muscular seas, and you'll feel at once very small and king of the world.

Far across the Seine Bay, mighty cliffs – notably around Etretat – have been sculpted by sea gods with time on their hands. (Erosion is far too prosaic.) In between, south of the Seine estuary, the almost over-cuddly Honfleur kicks off a coast of hills, coves and long beaches until, beyond Merville, you get to the yet longer beaches of the longest day.

Sword, Juno and the rest lead west around to Utah, a vast sweep of sands, cliffs and far horizons. It is impossible to recapture the terror as the good guys came ashore in 1944, but try: the effort is not redundant. These days, around the museums and memorials, the coast wears a jaunty seaside air. This is as it should be. The freedom to be jaunty was one of the reasons for the fight.

Scores: Brittany 9, Normandy 7

Normandy's 10 best beach hotels

Brittany's 10 best beach hotels

France's 21 most beautiful beaches

Towns and villages

Rooted decency – that’s the thing about Breton villages. Granite-grey, or sometimes whitewashed, they attenuate the wildness of the surroundings through the determined cultivation of hard work and hydrangeas. Among the loveliest is Pont-Aven, crammed into a wooded valley and painted to fame by Gauguin and chums.

All along the coast, though, other well-tailored spots have the charm of the resolute, overlooking sea, bays and inlets with which they came to terms long ago. They’re open to the ocean, but wrapped tight round the community. If you can wake up in Quiberon or Ste-Marine (in the south), Conquet, Ploumanac’h or Paimpol (north) without feeling chipper and sea-doggish, you’ve overdone the cider.

Roscoff is home to the Onion Johnnies. They pedalled Britain peddling Breton onions, thus establishing an unlikely paradigm of Frenchness in British minds. Quimper’s superbly-spired cathedral should be seen, best from the half-timbered Rue Kéréon. Ditto the walled centre in Concarneau – the only town I know whose summer festival commemorates an absence of sardines. Many of the bigger cities took a fearful hammering during the last war. Some (Brest, Lorient) have been put back together uncertainly – but not St Malo. Within the ramparts, its stone-built splendour has been restored. In an odd way, it reminds me of Florence. It is a stand-out.

Major Norman cities were also clattered in 1944 and re-built afterwards. Of them, Le Havre has been called “Stalingrad-on-Sea” but is more subtle than that. (Not difficult, granted.) Caen retains abbeys built by William the C. and Matilda as a bribe to the Pope to bless their marriage. Cherbourg has returned to dignity, vigour and a certain saltiness – while the centre of Rouen still leads atmospherically to where Joan-of-Arc was roasted. (“When?” asked a schoolboy last time I was there. “This morning,” said his teacher. “We missed it.”)

The Normandy littoral has been fashioned for the fashionable since the 19th-century. Resorts like Granville and Barneville-Carteret are overlain with memories of parasols and boaters, which works well in 2018. Near the Seine estuary, Honfleur has a sort of asphyxiation of charm, with artists to spare. Trouville is fishier and Deauville a protectorate of palace hotels, casinos and race tracks – the seaside filtered through the assumptions of the Parisian glitterati. It reveals new depths to one’s superficiality.

But it is to the inland Pays-d’Auge which I return most often. Here, half-timbered villages punctuate the deep-green landscape, confident in a prosperity of apples, cream and horses. Motor to Beuvron-en-Auge, Cambremer or Crèvecoeur to see what I mean.

Brittany 9, Normandy 7

The idyllic region that proves Britain and France have more in common than you think

France's 20 most beautiful villages

Landscape

Bisecting Brittany's far-west Finistère, the Monts-d'Arrée are where you learn how resistant you are to myths. The rounded hills – stirring and desolate – are home to the Korrigan little people and Ankou, the steward between life and death. The gates of hell are, apparently, nearby.

Elsewhere, inland Brittany alternates stubborn rises, woodland and some of France's most efficient farmland. Well-worked fields roll right to the serrated coast. And then, just west of Rennes, you're at the Paimpont Forest – fine, but stuffed full of Arthurian legend.

Over in Lower Normandy, there's a memory of Englishness about the wooded valleys and plentiful pastures, grazing cows, timber-frame farmsteads and apple orchards. Farther south, beyond Thury-Harcourt, the Suisse-Normande, though scarcely Alpine, rises to some tough crags and gorges. Around Argentan, we're deep in horse country, the Haras-du-Pin national stud enrolling nags in France's never-ending quest for grandeur. To the north, the Seine valley upstream from Rouen has meandering drama of its own.

Brittany 6, Normandy 7

Art and history

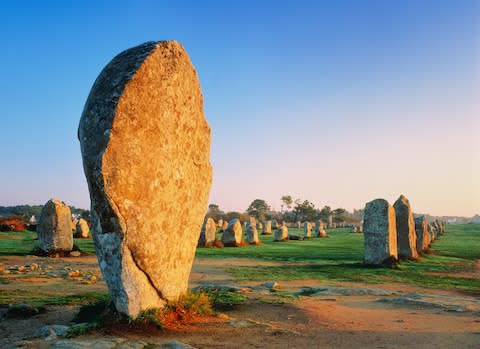

No-one knows why neolithic Bretons erected the extraordinary alignments of standing stones at Carnac. Astronomy? Seismic indicators? Druidic rites? I prefer to think they were recreational. Ancient Bretons simply liked putting up stones. There was, after all, no TV.

Later came the Christianising Celts, including Irish St Ronan who established base at what is now the gorgeously-preserved village of Locronan, near Quimper. Women wanting babies still show up for aid with conception, apparently Ronan’s sphere of influence. Brittany’s finest medieval castles are at Fougères and Dinan – whose wonderful half-timbered streets tell tales from the middle-ages through the 18th-century. And all Breton ports speak of ancestral trade, fishing and freebooting, none so clearly as St Malo.

Meanwhile, it was the romantic wildness which first drew painters to then-unexplored Brittany. The Impressionists followed, seeking sensations. Monet painted the tortured Port Coton on Belle Isle 36 times. At Pont-Aven, Gauguin turned Breton women into Tahitian look-a-likes (and then got mauled in a fight with seamen). And Brittany was attracting artists from all over Europe to celebrate its seductive nature - as is indicated by this summer's surprising season of Czech-Breton works at Quimper's fine arts museum. To September 30, 2018.

Normandy, too, was thick with Impressionists. From his home in Giverny, Monet was among those travelling to Dieppe, Honfleur and Trouville – from where he legged it, bills unpaid. He also, famously, became obsessed with the cathedral in Rouen, whose Fine Arts Museum is, incidentally, a belter. As is the Musée André Malraux at Le Havre.

History-wise, you will want to know about William the C. The best bet is his castle at Falaise – from where you might also take in the Montormel Museum, with its tough coverage of the August 1944 Falaise Pocket slaughter. The real emotional charge comes, though, on the D-Day beaches themselves, where museums and memorials abound.

Visit them all and you'll not be home for Christmas. My suggestions, going west-east, would be the Memorial at Caen, the best Second World War museum anywhere; the Juno Beach Centre at Courseulles where the Canadians came ashore; the Bayeux Commonwealth cemetery (with an offshoot visit to the tapestry); the United States cemetery at Colleville; and, finally, the Musée-du-Débarquement at Ste Marie-du-Mont, fronting Utah beach.

From there, it is but a hop to France's finest historical monument. To Brittany's chagrin, the Mont-St-Michel is just in Normandy. Mesmerisingly alone, the 550-feet rock-island abbey appears to have landed from a more majestic dimension.

Brittany 9, Normandy 9

Food and drink

Let's forget cider, a speciality of both regions. It is a child's drink in adult clothes. Local beers are better. I'm not much impressed, either, by the Bretons' crêpes, though I'm alone in that. There's roughly one crêperie-per-head-of-population across Brittany.

Let us rather consider the fish, seafood and seafood platters (lobster, oysters, clams, cockles and then some), perhaps eaten on the seafront at Cancale. Or the kig-ha-farz, a sort of Breton pot-au-feu. Or the far Breton flan. Tackle that lot and you're fettled for a fest-noz (night festival) and no mistake.

10 dishes you cannot leave France without eating

Nor is Normandy any slouch in the seafood stakes. If in doubt, try the Marmite dieppoise, fish stew with added butter and cream. In truth, dairy produce seeps everywhere in a region producing some of France's finest cheeses. Think Livarot, Pont-l'Evêque and Camembert. Beef and lamb are excellent, though you might like to hesitate before ordering Caen tripe or andouillette (intestines sausage).

Finally, and unsatisfactory though cider is, it does distil splendidly into calvados, than which nothing renders an evening more mellow. Christian Drouhin's 17th-century manor at Coudray-Rabut has some of the best.

Brittany 7, Normandy 9

Verdict

Brittany edges it by 40 to 39, (but who really believes such points systems?)