From Office Spaces to Workwear, See How the World of Work Has Changed Through the Years

iStock

Ch-ch-changes is the theme song for work in 2022, thanks, in part, to the pandemic. The traditional work world in the U.S. has been upended—from where we work and what we wear to how many hours we log. Here’s a Parade report on what’s changed and how.

Related: From Healthcare to Education, These Are the Hottest Jobs of 2022 and Beyond

Office Space, Then & Now

61%: That’s how many workers who have a workplace outside the home choose to work from home instead.

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed the first open office space, the Administration Building for SC Johnson Wax in Racine, Wisconsin, which opened in 1939. The building’s great room covered half an acre, with soaring ceilings, skylights, a forest of columns that bloomed into circles against the ceiling, and modular furniture, including oval desks, tables and rolling file carts. (The building is still in use today.) The room housed the secretarial pool, with offices for senior staff around the perimeter.

By the 1960s, businesses wanted more privacy for workers, but also wanted to fit as many people as possible into spaces. In 1968, the Herman Miller Research Corporation introduced the “Action Office,” a system that included flexible cubicles that gave workers some privacy but still allowed for lots of interaction. It was colorful (green, blue, navy, yellow) and included standing desks with footrests, moveable display surfaces and other revolutionary (for the time) touches. But as other companies copied the Action Office, it became less colorful and more like a network of functional gray cubicles. As high-tech companies began to proliferate in the 2000s, so did multipurpose workspaces, with non-assigned seating, designated lounge areas, community tables and ever-changing layouts.

Enter work-from-home life. A Pew Research survey in January found that 61 percent of workers who have a workplace outside the home are choosing to work from home instead. “People need to have a very compelling reason to come into the office now,” says architect John Campbell, who just retired as president of FCA, an architecture, planning and interior design firm. As a result, workplaces are transforming. What they’ll feature:

Conference rooms sans conference tables: “We had conference tables because people were taking notes and talking across the table,” says Campbell. “Now, more often than not, they’re looking at a screen.”

Fewer hard-walled spaces: Some rooms—conference rooms, pantries—will be enclosed, but offices will include flexible space dividers like credenzas with open shelves. “You’ll have certain fixed elements, then a dance floor for the other furniture,” Campbell says.

Less formal furniture: Comfy armchairs for long meetings, kitchen-table-like desks for co-working and areas with softer seating and lower light for a more home-like feel.

Improved ventilation and acoustics: Cleaner air and better sound allows for better collaboration with remote workers.

No assigned seating: Until the pandemic, most workers wanted their own desk or office. But “people realized they don’t have to be so territorial about office space.” Now, “the whole office is your space,” Campbell says. “It’s like home; you do different activities in different rooms in your home. Some are open, some are more private. Think of the office as an extension of that.”

Related: What People Earn 2022: What Everyday Americans Are Making

Work Tools, Then & Now

Fax Machines: In 2000, businesses sent urgent documents back and forth via fax, a machine that transmitted text or graphics from a scanner through a phone line to a printer. Fax machines were a ubiquitous part of office life for more than 30 years—some 25,000 fax machines graced offices in 1970. They cost $18,000, weighed 100 pounds and took six minutes to transmit one page, according to the Los Angeles Times. By 1991, home fax machines cost as little as $500, weighed 15 to 20 pounds, could send a page in 20 seconds or less, and some 3 million whirred and beeped in homes and offices across the U.S. The internet and email rendered fax machines obsolete by the early 2000s; now you can email documents in a second.

Rolodex: In 1956, office supply company Zephyr American patented the Rolodex, a rolling index of alphabetized cards for keeping track of all your business contacts. It was better than an address book because you could simply remove and toss outdated contacts and add new ones without running out of space. Now, contacts are stored on mobile phones, sim cards, computers and in the cloud. You can still buy a Rolodex, though; Amazon offers Rolodexes for as low as $22—refill cards are available too. And the Smithsonian museum has a Rolodex in its collection, preserved for posterity.

Computers: Even Apple’s most powerful laptop today (the $3,499 16-inch MacBook Pro Max) weighs less than 5 pounds. The first personal computer—purchased mostly by hobbyists—was the Altair 8800, which weighed 65 pounds. (You could buy a complete kit to assemble your own for $439: “If you can handle a soldering iron and follow simple instructions, you can build a computer,” promised a 1975 Altair ad in Popular Electronics.) IBM introduced its first PC in 1981, at a cost of $1,565. It weighed 25 pounds and included a disk drive. Apple introduced the Lisa PC in 1983, which flopped due to its cost ($9,995!), followed by the 1984 Apple Macintosh ($2,495) and finally, in 1989, the Macintosh Portable (cost: $6,500; weight: 16 pounds).

Watercoolers: When Luther Haws created a portable water-dispensing machine in 1938, the office watercooler—a spot where employees gathered to gossip and brainstorm—was born. It wasn’t long before “watercooler talk” entered the vernacular, and studies revealed that informal gatherings around watercoolers or coffee increased worker productivity by 10 to 15 percent. Now: Apps like WaterCooler connect co-workers virtually for informal conversations.

Related: What People Earn 2022: What Celebrities Are Making

Working Hours, Then & Now

+3 hours: That’s how many additional hours per day U.S. workers logged in 2020 as they tried to figure out how to work remotely.

If it feels like you’re working more hours than Americans did in the past, you’re partially right. In 1880, when the government first began tracking worker hours, the average full-time manufacturing employee logged about 62 hours a week. Throughout the early 1900s, labor unions pushed for shorter workweeks, and in 1926 automotive titan Henry Ford mandated a standard five-day, 40-hour workweek for all employees. In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, limiting the workweek to 44 hours; an amendment in 1940 cut it to 40 hours, where it remained enshrined for decades.

Enter the global pandemic of 2020, when U.S. workers logged an additional three hours per day on the job as they attempted to figure out how to work remotely. In early 2021, U.S. workers were still working an additional 2.5 hours per day, according to data from NordVPN.

Commuting, Then & Now

19%–65%: That’s how much the number of hours spent commuting plummeted in the top major urban areas during the pandemic when workers stayed home.

Average one-way commute time in the U.S.:

1980: 21.7 minutes

1990: 22.4

2000: 25.5

2013: 25.8

2019: 27.6

While the incremental increases in commute times over the decades seem small, consider this: That 21.7-minutes-each-way commute in 1980 adds up to 181 hours a year (assuming two weeks off for vacation). The fact that it took 6 minutes longer in 2019 ate up 230 hours a year—a difference of 49 hours, or three full days of time. One upside to the pandemic: Commute times and traffic congestion plummeted. In one study, the number of hours lost in congestion during peak commute periods dropped by anywhere from 19 percent to 65 percent in the top 20 major urban areas in the U.S.

Related: 30 Flexible, Stay-at-Home Mom Jobs for Women Who Want to Make Some Dough

A Dying Job

Then: Furriers were all-around craftsmen who could cut furs, operate a sewing machine and finish a garment. In 1949, furriers working in department stores and retail shops in NYC made a minimum $75 per week. By 1989, total retail sales for furs in the U.S. reached a record $1.9 billion, and furrier Jerry Sorbara told Business Insider he made more than $400,000 in a single day in 1986. Now: Furriers are no longer listed in the Occupational Outlook Handbook—the number of mink killed for their fur dropped by almost 50 percent and an amendment was recently passed in the House of Representatives to ban mink farming in the U.S.

Work Wear, Then & Now

31%: That’s how many respondents would take a 10 percent pay cut rather than dress up for work every day, according to a survey by online personal styling service Stitch Fix.

Everett Collection

’50s: Dark-colored suits, white shirts, dark ties and white pocket squares. Think Humphrey Bogart and William Holden in 1954’s Sabrina.

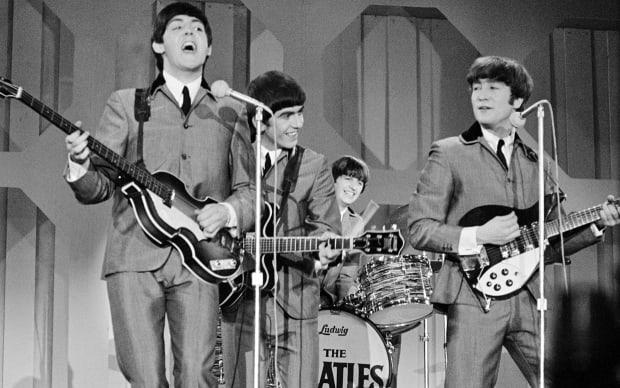

CBS via Getty Images

’60s: Ties, lapels and pants were all slim (à la the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964).

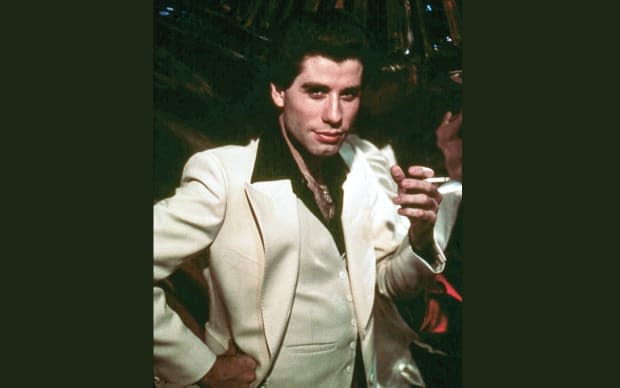

PARAMOUNT PICTURES / Ronald Grant Archive / Alamy

’70s: John Travolta in 1977’s Saturday Night Fever captured the spirit of the decade with wide lapels and polyester.

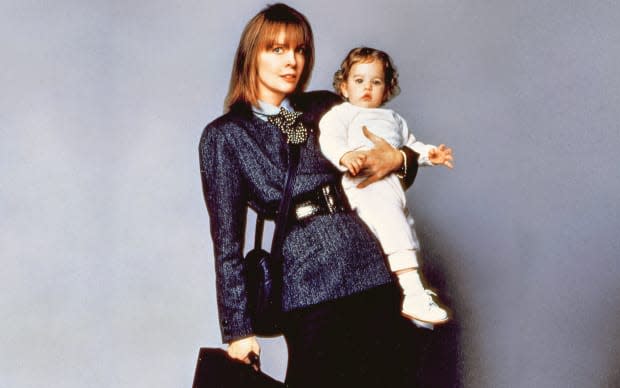

United Artists/Everett

’80s: Power suits roared in, with broad shoulders, pinstripes and double-breasted jackets. (Think Diane Keaton as J.C. Wiatt in 1987’s Baby Boom.)

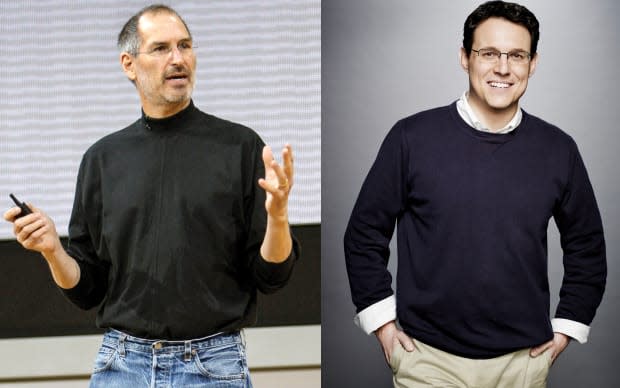

dpa picture alliance archive / Alamy / Art Streiber/MSNBC

’90s-2000s: Business casual became just casual as more workers embraced the laid-back turtleneck style of Silicon Valley’s Steve Jobs and Steve Kornacki’s MSNBC online uniform of khakis, button-down shirts and no tie.

In the new millennium, suits lost their luster. Investment bank JP Morgan Chase adopted a business casual dress code in 2016, as did consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers. When the pandemic shuttered offices in early 2020, workers shed suits for sweatpants overnight, and Brooks Brothers, makers of business suits for men and women, filed for bankruptcy in July 2020, followed by Tailored Brands (parent company of Men’s Warehouse, Jos. A Bank and others) a month later. Before the pandemic, 32 percent of workers surveyed by the NPD Group said they wore “casual” clothes to the office; now 40 percent dress casually for in-person work.

“We’re starting to see real change in how we think about dress codes and what getting dressed up even means,” says NPD apparel analyst Maria Rugolo. “There’s a transition to ‘work casual’ being actually casual and not ‘business casual.’”

Thanks to the plethora of pandemic-delayed weddings and hybrid in-office work, suits are slowly coming back, but the future of workwear is uncertain.

Related: 50 Tips to Break Out of a Career Rut and Make Your Day Job Feel Like Your Dream Job