One of the 1960s’ Greatest Musical Geniuses Just Published His First Memoir. It’s Quite a Journey.

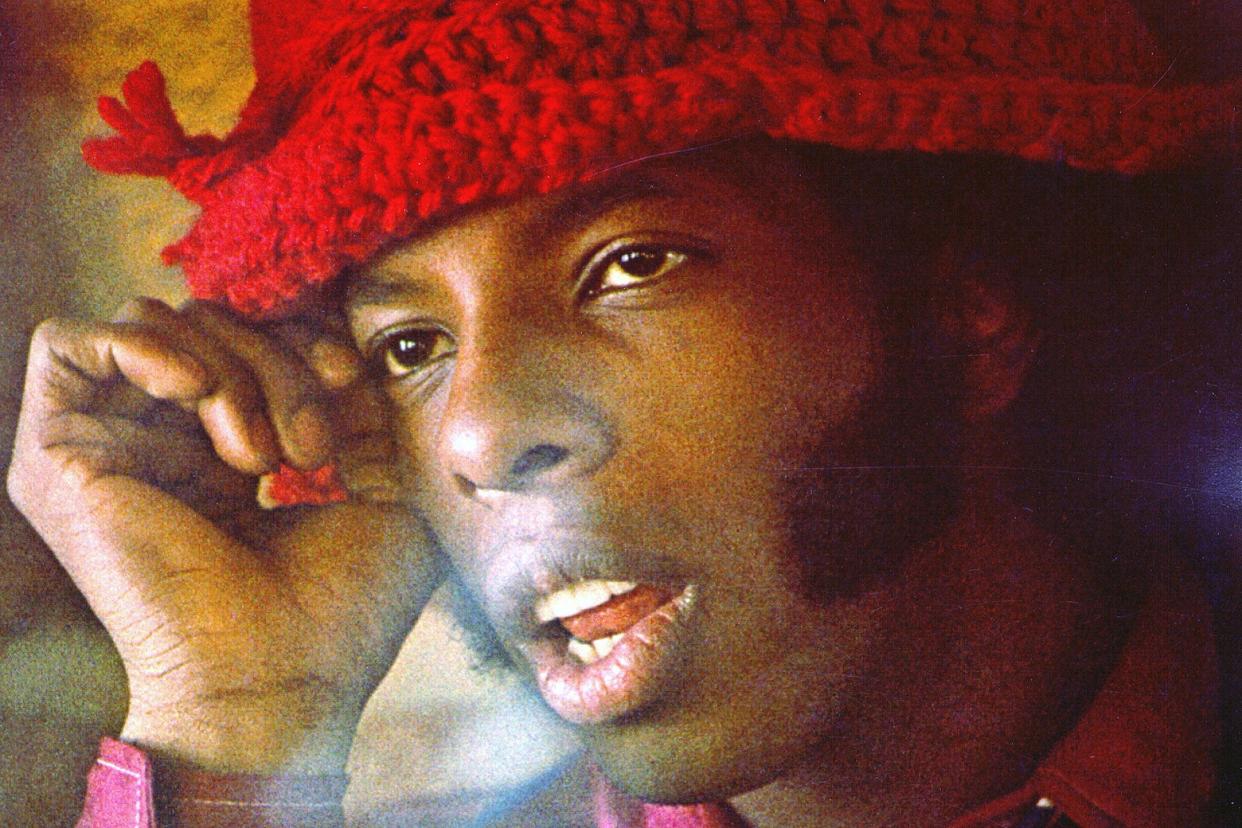

Very few artists have changed the course of popular music, and far fewer have managed to do so twice within a five-year span. Sylvester Stewart, better known to the world as Sly Stone, is in the latter category. In late 1967, Sly and his band, the Family Stone, released the thunderous single “Dance to the Music,” which reached No. 8 on the Billboard Hot 100, a chart position that does not begin to do justice to its impact. For the rest of the 1960s, Sly and the Family Stone were the bleeding edge of pop music, cresting in a performance at Woodstock that was one of the high points of the three-day festival. Then, after a (for the time nearly unfathomable) two-and-a-half-year hiatus between new albums, Sly returned in late 1971 with There’s a Riot Goin’ On, a dark, vexing, groundbreaking work that to no small degree gave birth to the future of R&B music.

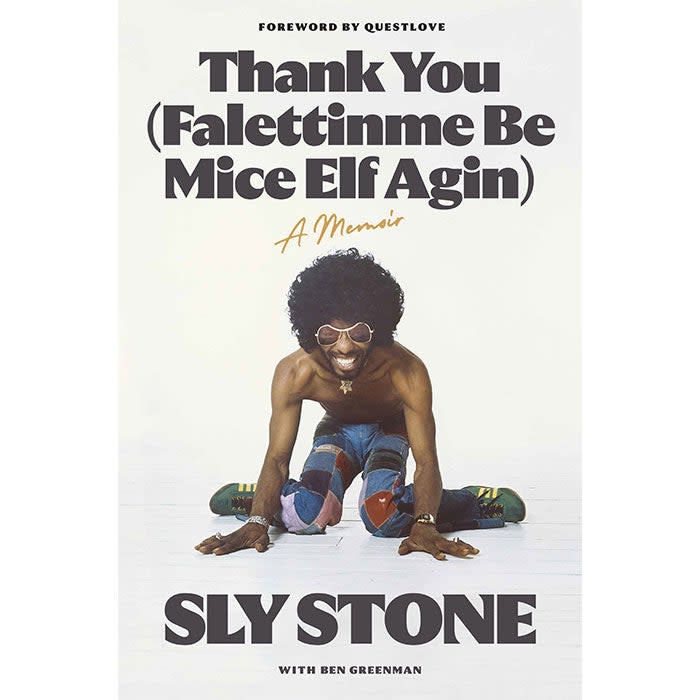

Sly Stone, now 80 years old, has just published a memoir, titled Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin). The first thing that must be said about Thank You is that it is a miracle that it exists at all. For decades Sly has been one of music’s greatest ghost stories, a man who had descended into a nightmarish spiral of drug abuse and effectively withdrawn from public life. From the 1980s on, pretty much every time that Sly was in the news, it was for something terrible: arrests for cocaine and gun possession, harrowing motorcycle accidents, and money troubles that reportedly left him homeless. There were a series of failed comeback attempts before he stopped even really attempting; public appearances were vanishingly rare, and tended to range from discombobulated to deeply disturbing.

Sly is now apparently clean and the author of what must be one of the most improbable music memoirs to ever make it to shelves. (Thank You is written in collaboration with author and journalist Ben Greenman.) Thank You is a brisk, crackling tour through the highs and lows of Sly’s life, from his career beginnings as a radio DJ and aspiring producer to his imperial period with the Family Stone to his long fall from grace. It’s a fascinating, revealing, and sometimes difficult read—as the 1970s progress, the book becomes more of a memoir of addiction than of music-making. As a stylist, Sly is conversational and often quite funny. His voice comes through loud and clear, ragged but unmistakably sharp. He hasn’t lost his penchant for aphorisms—this is, after all, the guy who once popularized the phrase “different strokes for different folks”—nor his natural ear for wordplay. (“I was half-watching the teacher at the blackboard and agreeing—black, bored,” he writes of an early recollection of elementary school.)

Many—maybe most—brilliant musicians aren’t particularly good at or even interested in reflecting on how they do what they do, which is one reason musician memoirs don’t tend to be very useful for actually learning about music. Thank You is better than some in this regard, but not so much so that it’s an exception to the general rule. In broad terms, this is fine, because Sly Stone is a musical genius: If Sly Stone or anyone else could easily explain how Sly Stone hears and makes music, he’d be probably be something lesser than Sly Stone.

But it’s also something of a shame, because one of the unfortunate side effects of Sly’s longtime reclusion is that his contributions to popular music have gone somewhat underappreciated, or at least misunderstood. As a mixed-race, mixed-gender outfit, the Family Stone is often celebrated for the late-’60s utopianism of their self-presentation, the significance of which can sometimes be overstated. (There had been mixed-race groups prior to the Family Stone, and mixed-gender ones as well, from Booker T. and the M.G.’s and the Jimi Hendrix Experience to the Mamas and the Papas and Jefferson Airplane.) What made Sly and the Family Stone so revolutionary wasn’t their demographics but rather their music itself: In the late ’60s, they were some magical bridge between the Beatles and James Brown, immaculate radio pop played by one of the greatest funk bands in history. Songs like “Everyday People,” “Stand,” and “Hot Fun in the Summertime” didn’t just capture the zeitgeist as vividly as anything Dylan or Lennon or Joni ever wrote, they were singular masterpieces of composition, performance, and recording. There was, and is, simply nothing else like them. One way of describing Sly and the Family Stone’s influence in this period—one that Sly himself invokes in the book—is that they had Motown playing catch-up: Suddenly new releases by groups like the Temptations, the Supremes, and the Jackson 5 sounded distinctly like they were trying to sound like Sly and the Family Stone. No one—not Phil Spector, not Stax, not even the Beatles—had ever achieved that with the mighty label out of Detroit. (“It sounded familiar: Cloud Mine,” Sly writes, another barbed pun that made me chuckle out loud.)

By the dawn of the 1970s, Sly and the Family Stone were among the most successful rock ’n’ roll bands on the planet. Their performance at Woodstock prompted more and bigger bookings, and Sly began developing a reputation for unreliability, for either showing up hours late to shows or missing them entirely. If drugs were taking a toll on the professionalism, they weren’t yet damaging the art. In December 1969, the Family Stone released two of their greatest recordings on the double A-side single of “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” and “Everybody Is a Star.” “Thank You” became the band’s second No. 1 hit and might be the darkest and most scathingly bitter piece of music to ever top the charts. (I mean this in an entirely positive way.) It’s a grim, lacerating song whose final verse openly mocks the aspirational optimism of Sly’s earlier music. It’s also one of the funkiest pieces of music ever made, which made it easy for listeners to miss the paranoia festering in its grooves.

Through 1970 and most of 1971, the world waited for a new Sly and the Family Stone album. When There’s a Riot Goin’ On arrived in late 1971, it signaled one of music’s greatest and most unnerving reinventions. Where previous Sly albums had been ebullient affairs, Riot was eerie and hallucinatory, like some avant-garde haunted house of funk and discontent. Sly recorded most of the album entirely himself and applied copious amounts of compression to the mix, resulting in a sound that is gnarled and sticky and entirely surreal. It was the first major pop album to make extensive use of a drum machine, specifically the Maestro Rhythm King, which can be heard prominently on the album’s lead single, “Family Affair,” which became Sly’s final No. 1 and is often cited as a crucial progenitor of 1970s disco. (For his part, in Thank You, Sly writes that he never much liked disco.) It’s the kind of record where the first time you listen to it, you worry something might be wrong with your stereo, and by its end, you feel like that’s the least of your concerns. At 52 years old, it remains an astonishing work of art.

Riot is probably the most influential album that Sly ever made, a work whose impact can clearly be heard on artists ranging from George Clinton to Miles Davis to Stevie Wonder to Prince. It also marked the beginning of the end of Sly’s reign—by the time he returned with an overhauled Family Stone on 1973’s magnificent Fresh, his personal dysfunction had become so well-known that the album was marketed as a comeback. Fresh was followed by 1974’s underrated Small Talk, which was followed by 1976’s not-particularly-underrated Heard Ya Missed Me, Well I’m Back, after which Epic Records dropped him. He released two more albums with Warner Bros., but following 1982’s Ain’t But the One Way, Sly Stone has not released an album of new material in 41 years.

Thank You leaves it ambiguous when, exactly, Sly finally got clean, but it’s clearly quite a recent development. (The book’s promotional materials place it within “the past few years.”) Sly began using cocaine in the mid-1960s, which suggests that, by a conservative estimate, Sly spent at least half a century as a serious drug user. Thank You has the air of a man who has finally surfaced, in ways that are alternately disarming and disquieting. At times he can be glib and defensive about episodes from his life that seem pretty indefensible, an unfortunate if understandable tendency for someone in the very early stages of recovery. He has a penchant for poring over old record reviews, magazine profiles, and television segments, often arguing with their characterizations in ways that can feel oddly nitpicky. After a while of this, it dawned on me that one reason Sly was spending so much time on articles that were often 40 or 50 years old, and watching old YouTube clips of himself, might have been that, in writing this book, he was essentially researching the details of his own life, a surreal situation to think about.

For those of us who love Sly’s music and have wondered and worried after him for years, Thank You is a bittersweet book, both a welcome indicator that Sly is very much still here and a sad reminder of a life and talent dimmed by so many decades of abuse. It’s an unusual, fitfully beautiful, and surprisingly emotional reading experience, and by its end I realized that it had left me with something previously unthinkable, one more act of self-reinvention from a genius of American music.