Patrick Kelly Dressed Everyone From Princess Diana to Grace Jones in the '80s — and His Work Is Still Relevant Today

A Derrick Adams exhibit at SCAD explores his legacy.

He referred to himself as the "black, male Lucille Ball." Essence considered him "a breath of fresh air in an industry that often takes itself too seriously." He dressed the likes of Grace Jones, Princess Diana and Paloma Picasso, and was known for his exuberant designs and spirited runways. For many, Patrick Kelly represented joy.

His contributions to the fashion industry are profound — he's been the subject of museum retrospectives before — but his legacy has just recently started receiving mainstream recognition. (He died in 1990.) With an exhibition from the Brooklyn-based artist Derrick Adams at the SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film inspired by his work and a biography on the way from esteemed academic Dr. Eric Darnell Pritchard, it's likely that his name will become a greater part of the fashion consciousness.

"I was aware of who Patrick Kelly was as a designer and his legacy but I didn't really know about Patrick Kelly the person, which is why the archive was so important," Adams said on a panel hosted by SCAD deFINE Art in Atlanta.

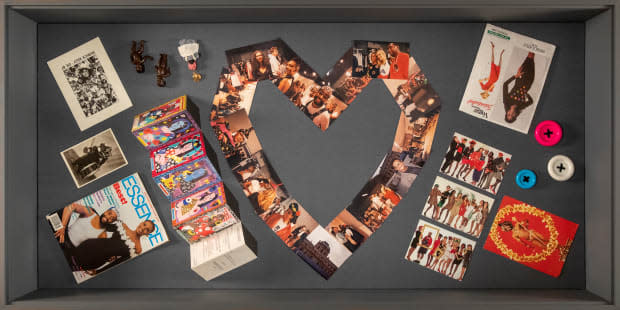

To prepare for this project, Adams immersed himself in Kelly’s archives at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. He discovered a trove of artifacts including sketches, swatches, memorabilia, and personal correspondence belonging to the African-American designer — all of which laid the groundwork for an exhibit that first debuted at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2017. For the SCAD show, the large-scale collages and sculptural works are displayed alongside archival items on loan from Kelly's friend Carol Martin — including dresses by the designer, newspaper clippings, and a fashion show invite — for the first time.

"I discovered in the archive that there was a proposal from Dr. Maya Angelou requesting support from a publishing company to produce a book on Patrick Kelly. It was making a plea about how important it was that a book be made about this person at this particular point in history. She said that it should be titled Patrick Kelly: The Journey, so when I was putting together the work I thought the most fitting title would be a reference to the letter."

Kelly was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1954. He attended segregated schools until his senior year of high school. On a 2019 episode of the "Dressed" podcast, Dr. Pritchard explained how "that race context informed his social, political, and cultural beliefs. He grew up in a rich context for thinking about individuality, democracy, diversity, difference, and inclusion as things to be fought for and celebrated."

Kelly's interest in fashion came from the women in his life — and particularly the fashion magazines his domestic-worker grandmother would bring back from the homes she cleaned to give to him. "He'd look through those and really loved the images that were in them but he also noticed black people were not in those magazines," Pritchard said on "Dressed." "He knew that black culture and style was important enough and significant enough to be the center subjects. That gave him the gumption to want to get into fashion."

After a one-year stint at Jackson State University, Kelly moved to Atlanta and began working at an Yves Saint Laurent boutique. He would make clothes for his friends on the side for their nights out (dubbed locally as "The Kelly Kids"). It was there he met model Pat Cleveland, who would encourage him to move to New York City to pursue fashion. But his journey wasn't easy: A Parsons scholarship he had received was rescinded and he was unable to secure a job with any of the fashion houses, many of them American sportswear labels that at the time didn't jive with his artistic sensibilities. After a little over a year, Kelly headed to Paris — and it was there that he would achieve in a few years what many aspire to in a lifetime.

In France, Kelly presented collections that were met with massive approval. He cultivated a community of expatriates and local creatives in the Marais. He became the first American to be accepted into the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter, the governing body of the French ready-to-wear industry.

"I think he made it in Paris because of hard work, opportunity and serendipity," Pritchard told Fashionista. "Looking at Paris fashion in the '80s, it was an open community for creativity in work. At that time, if you had a new idea, they were really excited about the new idea."

Kelly's designs were colorful and cheeky, often incorporating unexpected elements ranging from mismatched buttons to racially-charged imagery. "He was definitely a purveyor of it," Pritchard said of how Kelly would use these racist symbols in his work as a way of subverting them. In a 2004 article for the Washington Post, Robin Givhan mused that "no other well-known fashion designer has been so inextricably linked to both his race and his culture. And no other designer was so purposeful in exploiting both."

Kelly's life was tragically cut short in 1990, when he died due to complications from AIDS. To Pritchard, that might be a reason why most people don't know his name: "This was at a time when so many people — many of them creatives in the fashion and art world — were also ill and passing away. My theory is his legacy got swallowed up in the sea of individual and collective grief and mourning."

That doesn't mean his legacy isn't felt, though: Pritchard sees Kelly's work as embodying black exuberance and black joy, themes seen in the collections of Christopher John Rogers, Mimi Plange and Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss today.

"I think Kerby's doing something that's very unique. He's not trying to be Patrick Kelly or even engage in the exact sort of vocabulary or glossary of black identity," Pritchard explained. "But I do think they share a similar cultural politic." (Adams actually collaborated with Jean-Raymond on his Spring 2019 collection for Pyer Moss, creating 10 paintings based on old family photographs that were then printed onto garments.)

"[Jean-Raymond's] use of gospel choirs for the performance atmosphere of a Pyer Moss show is also very similar to how Kelly thought of a show as an event," Pritchard continued. "I think he's very unapologetically black and Kelly was unapologetically black."

This notion of black joy as empowerment is something that permeates Adams's ethos as well. "When you look at Black History Month in school you never see pictures of James Baldwin dancing with Maya Angelou on the wall. That's the image you should be putting in kid's classrooms," he said. "When I started to think about leisure and seeing the black body in a form of rest and enjoyment, to me that was political. We as a culture often feel like those images are not as powerful because we were taught that we have to look like we're fighting in order to look relevant. But to me, when we're at the most creative and most gathered in the community, that's when it's most threatening. If you're still thriving in the face of adversity and oppression, that shows me the culture's still thriving."

Patrick Kelly: The Journey is on display at SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film in Atlanta through July 19.

Disclosure: SCAD paid for my travel and accommodations to visit its exhibition in Georgia.