From Pepys to TikTok – how the bawdy ballad stood the test of time

It’s half a century since Disney released its 1973 cult classic, Robin Hood. In 83 minutes of zany animation, the medieval legend was played out by a “merriest menagerie”, a cast of anthropomorphic animals. Robin Hood was a fox, along with Friar Tuck (a badger), Prince John (a lion), Maid Marian (a vixen), and a troupe of elephantine trumpeters. It’s hardly rooted in historical accuracy. Yet it is a tribute to a key feature of England’s medieval musical past: the ballad. The word “ballad” derives from the Latin ballare, meaning to dance (the same origins of the word “ballet”).

These were simple songs, performed by wandering minstrels, or recounted by ordinary people with friends and family. They often had simple ABCB structures, forming four-line stanzas called quatrains. The result was music to please the masses, with snappy rhymes, lilting rhythms, bawdy narratives and outlandish characters.

It was such ballads that sustained the legend of Robin Hood. We don’t know who the real Robin Hood was, if he existed, or how the tales came about. But by the 14th century his name was established in folklore: in 1377, William Langland mentioned the “rymes of Robyn hood”, so well known they required no further explanation.

There are plenty of nods to such songs-of-old in Disney’s wacky retelling. The animalistic casting hammers home its origins in fable, not fact. Once more, Alan-a-Dale (a rooster with the deep voice of Roger Miller), narrates the film in the guise of a wandering minstrel: “an early-day folk singer”, as he puts it, whose “job is to tell it like it is, or was, or whatever”.

There are ballads throughout too, such as The Phony King of England, which laments how “We’ll all have to slave away / For that good-for-nothin’ John”. This was based on a real, more recent (and less PG) ballad, The Bastard King of England. In the original, the unnamed English king is described as “dirty and lousy and full of fleas”, who “had his women by two and threes”. The Queen of Spain was “an amorous dame” who “longed to fool with his majesty’s tool”.

Such double entente has long been a feature of ballad tradition, which grew to new prominence in the 1660s. Alongside retelling myths and legends, ballads began to recount contemporary news. Details of elections, executions or celebrity gossip were circulated widely “with the method of a Ballad”, acting as a kind of tabloid press. Ballad-mongers, -singers and -makers became familiar faces of street corners, fairs or in town squares, bellowing their songs to passers-by. One ballad singer working in 1687 was recorded as “Andrew Flower, born at Northampton… tall and slender, round-faced, black brown short curled hair, aged about 23”.

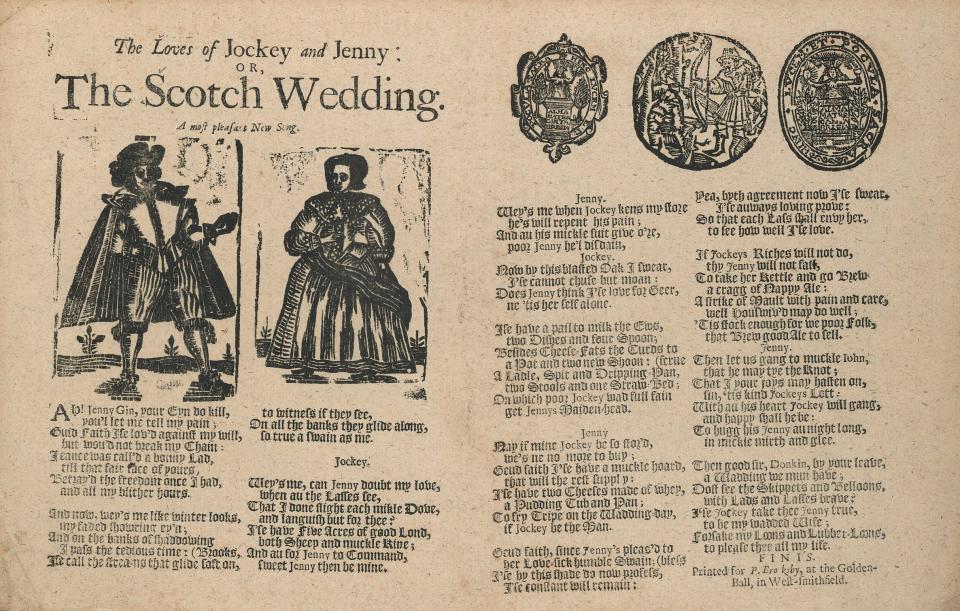

Keen punters could also purchase their own copy. These were cheaply printed on thin sheets of paper called broadsides. Alongside the lyrics were suggested tunes (Greensleeves and Lavender’s Blue were popular), or titillating woodcut prints. One 1689 broadside describing Mary of Orange was accompanied by a risqué image of a woman (possibly Mary) with breasts fully exposed and face covered in “patches” (a method prostitutes used to cover up pockmarked skin).

These images would adorn outside walls or taverns, so only one side was printed. Some punters bought them to enjoy then discard. Others recycled them to line cake tins or use as lavatory paper.

Indeed, vulgar jokes were common. In one ballad, titled The Praise of Nothing, readers were teased by a saucy pun, based on the different meaning of “nothing”. It could mean the absence of anything, the meaninglessness of human existence, or – and here comes the bawdy humour – a euphemism for female genitalia. While dismissing a “scolding wife” and the “harlots love”, the ballad concludes that men could be “help’d by nothing”.

The reaction was mixed. Newspapers decried such ribaldry as “obscene”, “lamentable” and “scurrilous”. In 1697, “several women were taken into custody for singing a Ballad”. Yet others considered ballads collectors’ items, such as the jurist John Selden. He saw them as a valuable measure of society, declaring that “More solid things do not shew the Complexion of the Times so well as Ballads and Libells”.

Samuel Pepys was another collector, owning 1,800 broadsides by the time of his death in 1703. Pepys organised them carefully into categories: “Love Pleasant”, “Love Unfortunate”, “State and Times” and “History, True and Fabulous”. Within this mixed bag was a good dose of smut. In a 1678 ballad titled, My Dog and I, a seemingly innocent story was given a filthy alternative meaning, when the word “dog” was taken as a replacement for male genitalia: “I loved a maid her name was Nell, / A bonny Lass, I lov’d her well, / If you’s needs know the reason why, / Because she lov’d my Dog and I’.

It was the writer and dramatist John Gay, who brought these “come at ye” ballads to centre stage of London culture. On January 29 1728, Gay’s new drama, The Beggar’s Opera, premiered at Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre. It was an instant hit, becoming one of the most performed plays of the 18th century. Set in the criminal underworld of Newgate Prison, it was a comic romp through sizzling celebrity scandals, highwayman heroics, and daring jibes at the corruption of the prime minister, Robert Walpole.

But most strikingly, instead of following the usual format of Italian opera, Gay embraced the popular ballad, interspersing it with dialogue. This is mentioned in the opening scene: “I have not made my opera throughout unnatural, like those in vogue.”

Indeed, Gay’s characters were true to life. One scene depicts a quarrel between two bickering heroines, Polly Peachum and Lucy Lockit. This was an explicit nod to a recent scandal that had rocked the opera world: a spat between Handel’s star sopranos, Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni. Yet their squabbles were now ridiculed in Gay’s ballad form: “Why how now, Madam Flirt? If you thus must chatter”, one heroine jibes, provoking a retort: “Why how now, saucy Jade; Sure the Wench is tipsy!”.

The ballad form has reared its head in different ways in recent centuries. Ordinary people continued to relish the “smut, scandal and debauchery”, as well as learn of the latest news (such as the 1819 Peterloo Massacre). Literary elites grew interested, too: Romantic poets such as Coleridge and Wordsworth utilised the form to conjure a bygone medieval past, and later, in 1897, Wilde produced The Ballad of Reading Gaol. Today, we are familiar with blues, rock and power ballads.

But what of the classic bawdy ballad, which seems to have disappeared? Were lewd drinking chants of football fans the final hurrah? Will it ever return? The answer lies, perhaps, on TikTok. Twenty-twenty marked a ballad comeback, when a performance of The Wellerman Song went viral. Although often mistaken as a sea shanty, this ballad was performed millions of times across the world via the app, endlessly remixed, translated and reinvented.

A new craze emerged: #shantytok. How strange that once again, these catchy, sometimes bawdy songs were enjoying a revival. Just like our medieval ancestors who heard ballads of wandering minstrels, today’s TikTok users stumble across songs of old as they scroll, and – alongside millions of strangers across the world – build a community singing, sharing and revisiting the ballad form.

Through this most modern medium, an ancient tradition is given new life. Yet again, the course of history is full of surprises, or as Alan-a-Dale put it, as he closed the 1973 Disney film, “Well folks, that’s the way it really happened”.