How This Plantation Is Reframing Antebellum History

“From a descendent person’s perspective, it's difficult to move out of the shadow of the plantation to get recognition for our community needs,” says Dr. Joy Banner, the Director of Communications at the Whitney Plantation Museum in Edgard, Louisiana. She is a descendant of enslaved people who toiled on the St. John the Baptist Parish site, which lay within the 54-mile stretch between New Orleans and Baton Rouge colloquially called “Plantation Country.” This picturesque region has become a tourist haven for architectural enthusiasts and horticulture fans, who often look past, beyond, or away from the brutal history of slavery tucked just yards away from the stately colonial houses. The Whitney Plantation Museum is uniquely positioned in the region, and within the country, as one of two plantation grounds devoted entirely to the life, labor, and culture of the enslaved people who lived there.

In 1867, the plantation was purchased by Bradish Johnson, who renamed the site for his grandsons (their last name was Whitney). When John Cummings bought the property nearly 30 years ago, he had no idea that his investment would turn into this sacred memorial for victims of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. As Banner tells it, “he thought ‘I’m a rich southern gentleman and so a plantation seemed like something that a rich southern gentleman should own.’ So it was part of his real estate portfolio, but in the purchase of the property and doing the research about slavery he was encountering documents—legal and otherwise—that painted a picture of slavery that he had never been taught.”

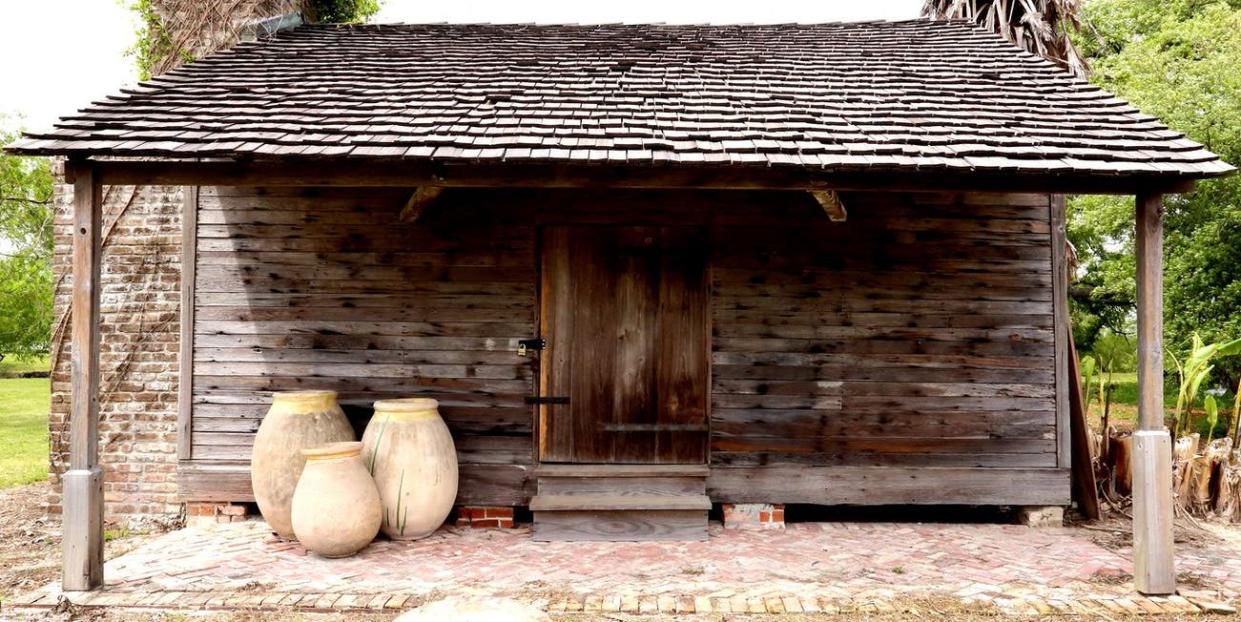

Cummings, who is white, poured decades worth of time and around $10 million into this personal restoration project, before ultimately dedicating the 2,000 acre plantation to teaching people about slavery. When he retired in 2019, he donated the plantation museum to a non-profit 501 c(3) with a predominantly African-American board. Currently, the site houses 16 historical buildings and two original slave cabins. Before the Civil War, there were 22 such cabins.

Under prior ownership, most of the cabins and outbuildings were bulldozed to make the property more profitable for cane sugar production and, later, for resale value of the land. Today, industrialization has complicated the process of calculating property values along this stretch of the Mississippi river, but Dr. Banner explained the museum’s challenges are great. “The main house is from 1791,” she said, “so this is an expensive operation. But we want as many people as possible to access the site and come to learn.”

My firsthand knowledge of the Whitney’s experiential approach came in 2019, when I visited the plantation on an exhaustive research visit to New Orleans to study the effect of layered European colonizations on the lives of African-Americans subject to servitude. I arrived heavily pregnant, and had no idea that this museum’s storytelling vision was through the lens of the enslaved children, who historians and Workers Progress Administration records showed lived and worked on the site. A Freedman’s church, which was moved to the grounds from a nearby parish, serves as a centerpiece for the historical interpretation. Upon entering, it was hard to take my eyes off the statues of children placed throughout the room. Eventually, a volunteer tour guide offered us cards, much like the ones I had received months earlier when visiting the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. These bore the names and brief biographies of enslaved children who had once lived on the plantation. Later, my tour group was given the opportunity to roam around the chapel to meet our child’s physical rendering in clay by Ohio-based artist Woodrow Nash. We continued the rest of the tour imagining life from the vantage point of children as young as five and as old as 15.

Memorials throughout the grounds offer snapshots into some of the revelations from archival documents. Lists of names, ages, and vague origins are etched into the black granite in the Wall of Honor, dedicated to all the people who were once enslaved on the plantation. A short walk away is Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, an outdoor tribute that bears carvings of archival content found through Hall’s decades of research, all too neatly called the “Louisiana Slave Database.”

I found myself engrossed in reading the stories from the 1800s. I was only interrupted by the chime of commemorative bells far off in the distance. As the tour progressed, my tour group was invited to toll them whenever we wanted to acknowledge these ancestors. The guide explained that these bells were once purposed as clocks that demanded enslaved people make haste to a particular place or task.

"This site is not just meant to be a historical site where people come and see a house," Dr. Banner reiterated. "This is not a house tour; it is educating people about slavery. It's also remembering the people who were forced to labor and die here. So the memorials are more contemporary, but they have become the most powerful feature of this site.”

Etched into my memory is the The Field of Angels memorial, where I rubbed my own belly in bitter disgust and utter sadness. A bronze statue by Rod Moorehead called Coming Home shows a black angel carrying a baby to heaven. When I was there, the statue was surrounded by benches where small baby dolls had been placed as a tributary addition. Almost in dialogue, the new and the old aspects of the memorial showed just how necessary—and powerful—the work of the Whitney truly is, especially in a country that has often attempted to brush over unpleasant parts of its past. “Children were not spared the brutality, the imprisonment, and the atrocities of slavery,” reminded Dr. Banner. “The representation of the children is a way of connecting with people's humanity, softening their hearts, and opening their eyes."

The Whitney’s website reads:

"Death rates on Louisiana’s cane plantations were relatively high compared to cotton or tobacco plantations. Many of the children honored at this memorial died of diseases, but some of them died under tragic circumstances such as being hit by lightning, drowning, or burning. The Sacramental Records of the Archdiocese of New Orleans also reveal a prevalence of young mothers and high mortality among their children. This is also apparent in the documents related to Whitney Plantation, which show that some women enslaved here had their first children by the age of 14. During the period 1823-1863, the era depicted in this memorial, thirty-nine children died at Whitney Plantation, almost one per year. Only six had reached the age of five.”

In this way, the museum is remarkable in its unabashed emphasis on local histories, no matter how brutal. One of the newest memorials highlights the Haitian revolution-inspired 1811 slave revolt that took place in St. John the Baptist parish. “Most people do not realize that we had the biggest revolt, likely in this whole country," Banner says. "It happened right here in our backyard. So, it was important, geographically, for people to be aware that this happened in the middle of ‘Plantation country,’ which the region is problematically called."

Its a reference to a crucial part of the history of slavery, as Banner sees it: "In my opinion, being enslaved came with as much resistance as it did enslavement," she says. "I call the participants of the rebellion revolutionary. They were fighting for the same freedom that the Americans fought for in 1776."

"It is important to have people realize what happened," she continues. "The monument is not subtle, as people often like to say, but it depicts the lengths that people went through to protect the institution of slavery. It shows their level of bravery and shows a level of resistance. Even though it was not successful, with two years of planning, it was very strategic. They were able to accomplish a lot within the system of slavery. It's a testament to their bravery."

The impact of an in-person visit is unparalleled, but the museum has adapted to the realities of COVID-19. Virtual programs for Juneteenth and other events have seen strong online attendance, particularly from people who live well beyond Louisiana's borders. In this way, the digital footprint has continued and expanded to new audiences, despite the fact that tourism has generally slowed over the last year. Yet, like many other sites of slave memory along the Atlantic Ocean, there is still an inherent tension around whether or not these places of pain should be preserved and monetized.

When I asked Dr. Banner her view, she was audibly troubled. “It's a two-edged sword, tourism,” she began. “These plantations actually created the historical problem that we have, but they are one of the things that are protecting us, sort of. Plantations with historical designation and the fact that within the sugarcane fields you have unmarked burial grounds that we're trying to legally protect means a kind of defense against over-industrialization.” She pointed out that historical “Plantation Country” directly overlaps with present-day “Cancer alley,” a contentious assortment of manufacturing and petrochemical plants that are the center of many environmental racism protests throughout Louisiana’s river-side parishes. She explained that, in this region, tourism and the plants are at loggerheads, but neither truly prioritizes the many descendants of enslaved people who still live and work on these lands today.

While the Whitney Museum does not currently focus on reparations, the institution is heavily emboldened by a sense of social justice. The museum board is currently trying to thwart efforts to build a plant next door that Dr. Banner says could install three hundred foot high structures and spew asthma-aggravating grain dust. “I'm a descendant of Whitney and I'm a native of this area. I'm still a resident here,” she passionately declared. “I want there to be more descendant-owned businesses. A lot of major issues are going on, but either people are focused on the plants or the tourism, not the people.”

Banner hopes that those who visit the plantation will choose one particular cause–human trafficking, child labor, environmental justice, minority rights, African-American empowerment—to champion in honor of the Whitney. “Spend some time reading online about at least one topic and I assure you it is going to lead to eye-opening, meaningful experiences of understanding what's happening here and about the challenges that humanity faces today," she says. "Learning about slavery and its history is something that needs to go on beyond the grounds of this plantation."

Follow House Beautiful on Instagram.

Nafeesah Allen is an independent researcher with an interest in literature, gender, and diaspora studies in the global South. In 2019, she completed her Ph.D. in Forced Migration from the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in Johannesburg, South Africa. She leads BlackHistoryBookshelf.com, a book review website that highlights global Black histories organized by language, theme, and country. Follow her on Twitter or Instagram @theblaxpat.

You Might Also Like