What really happened to Natalie Wood, according to her sister

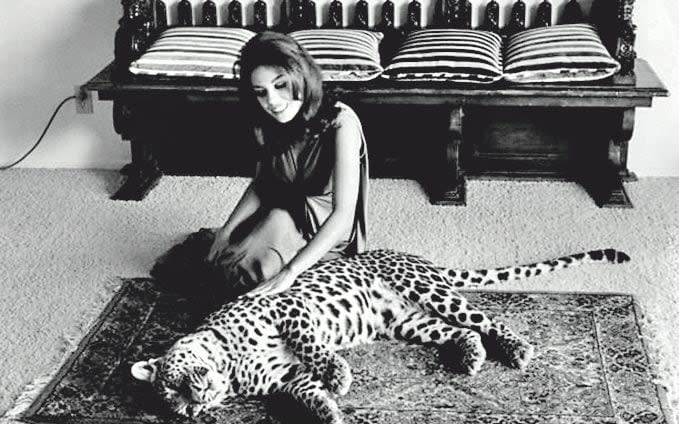

Natalie Wood was 43 when she died. No age at all. A Hollywood icon, she had made her film debut at the age of four and risen to become one of cinema’s most successful and garlanded stars: Maria in West Side Story and Wilma Loomis, the young girl driven mad by love, in Splendor in the Grass.

But by November 1981, she was at that difficult place for any actress of the period, as her younger sister Lana puts it, ‘caught in the cruel transition from “major star” to “who?”’. She was working on a science-fiction thriller, Brainstorm, and readying to make her stage debut in Anastasia.

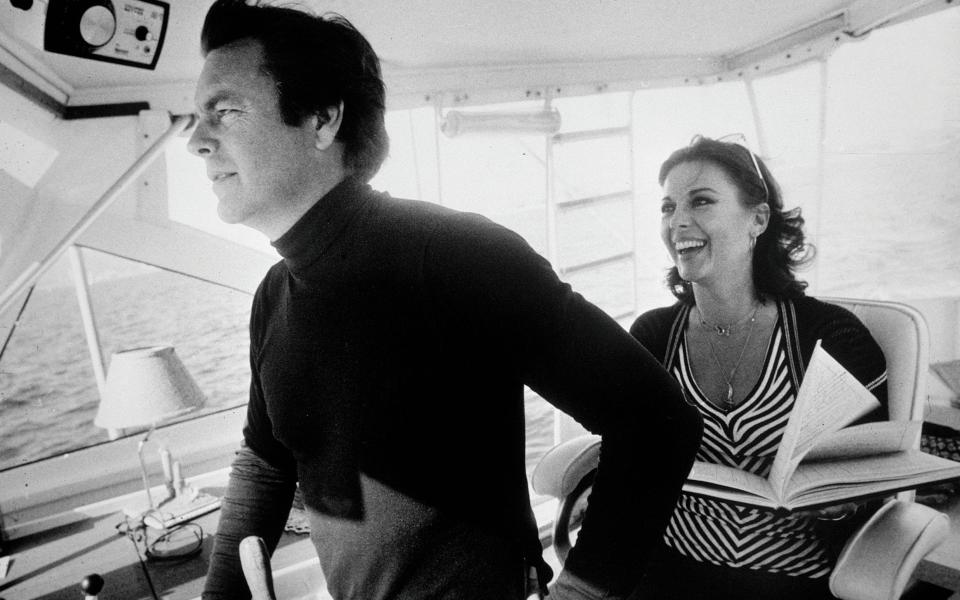

In the last week of November, Wood, along with her husband Robert Wagner and her Brainstorm co-star Christopher Walken, set off on a Thanksgiving-weekend sail off the California coast, on the couple’s 55ft yacht, Splendour.

Early on the morning of 29 November, her body was found floating in a Catalina Island cove.

In the 40 years since, Wood’s death has been a source of abiding curiosity and speculation. It has fuelled books, documentaries and hundreds of newspaper articles, all circling in the end to the same question: was Natalie Wood’s tragic death an accident, or is there another, darker explanation? In short: did she fall, or was she pushed?

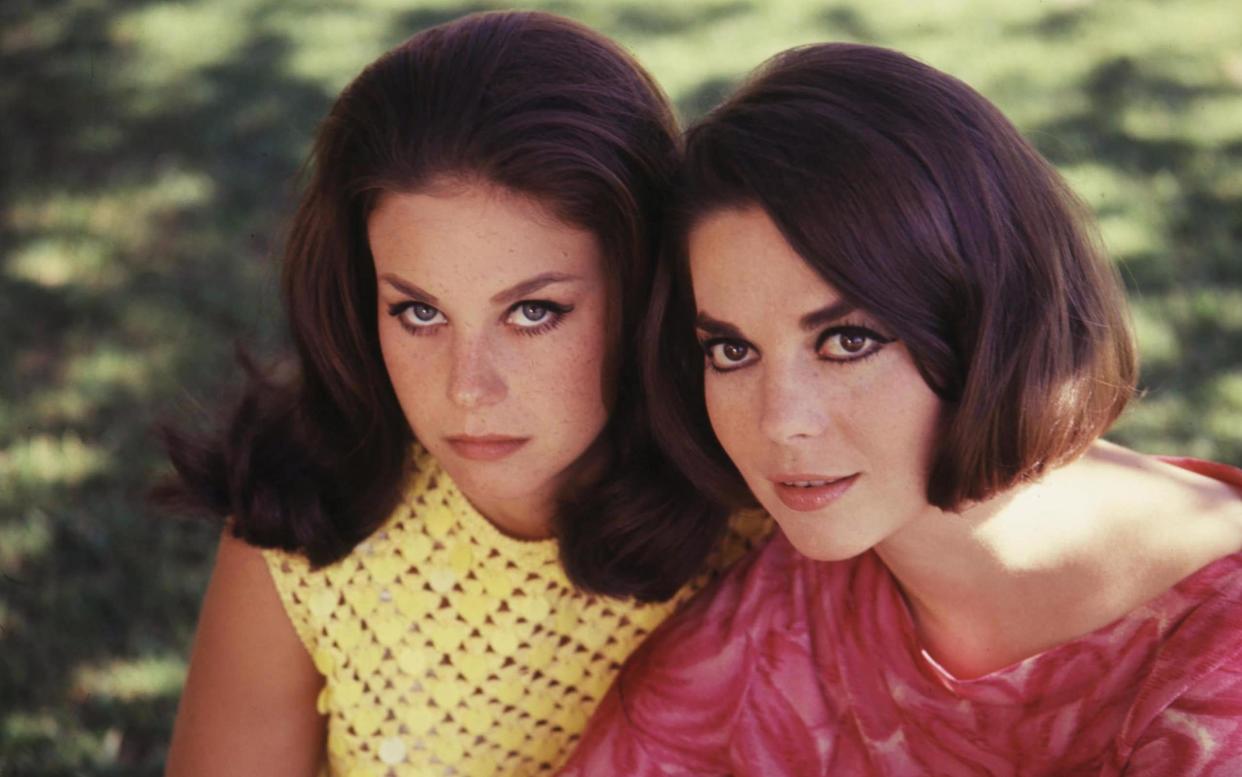

It is the question that has tormented Lana Wood. ‘There have been so many bizarre stories where people find one fact and twist it and turn it so it’s become an entire story of fantasy,’ she tells me, speaking from her home in Los Angeles. ‘There have been very untrue and unkind things said about Natalie. And it seemed like no one had Natalie’s back.’

Lana published Natalie: A Memoir by Her Sister in 1984, but now she has written a new book, Little Sister, published this week, which dwells on her struggle over the years to come to terms with Natalie’s death, her attempts to ascertain what exactly happened that night, and the new evidence that has come to light since the first police investigation.

‘Life,’ she writes, ‘never got too busy to obscure the elephant in the room – that oppressive combination of grieving the loss of my sister and still not knowing exactly what happened to her.’

We have arranged to speak by Zoom, although she prefers to keep her camera switched off. But her mood and demeanour are clear in her voice. She is now 75 and her anger over her sister’s death and at the man she believes to be responsible remains undiminished after four decades.

Their parents were Russian émigrés who had settled in America in the aftermath of the revolution. Their father, Nikolai, worked as a set-builder in Hollywood studios – a ‘very quiet, very tormented’ man who would disappear to his room, decorated with pictures of the Russian royal family, to drink vodka and rail against the Communists. Their mother, Maria, was a domineering woman whose advice to her daughters was, ‘Don’t have girlfriends prettier than you,’ and who stopped at nothing in her ambition to make Natalie a star. ‘She was just in complete adoration of Natalie, show business, the parties, everything. She lived for all of that.’

Lana tells the story of being driven with her mother and sister one night to the Chateau Marmont hotel. While Maria and Lana waited in the car, Natalie was sent to a room where Kirk Douglas was waiting. According to Lana, her sister returned ‘dishevelled and very upset’. It was only some years later that Natalie confided that Douglas had sexually abused her. She was just 15. Lana was too young to understand what was going on, but old enough, she says, to realise that ‘something was very, very wrong. But it just reaffirmed my view of my mother, her attitude to stardom and how Natalie should behave: gee, that’s terrible, now shut up about it.’

In 1957, Natalie married Robert Wagner, then a movie actor whose career was faltering, but would later revive spectacularly with the television series It Takes a Thief and Hart to Hart. Natalie was 19; Wagner, known to his friends as RJ, was eight years older. A Los Angeles Times columnist described them as being ‘the most photographed, talked-about, envied couple since Wally Simpson and Edward VIII’. But in 1962 she and Wagner divorced, after Natalie, according to Lana, found Wagner in what Lana describes as ‘a very compromising position’ with his butler, an allegation Wagner has always denied.

Natalie embarked on a series of affairs: with Warren Beatty; a Yugoslav playboy named Ladislav Blatnik – ‘a silly man’; Tom Courtenay; and the politician Jerry Brown. In 1969, she married British producer Richard Gregson. They had a daughter, Natasha, born in 1970, but divorced, Lana says, after Gregson cheated on her.

In 1972, Natalie married Wagner for the second time. (Two years later they would have a daughter, Courtney.)

‘I really felt I was losing my friend. And to be true, I did lose her to RJ. When they announced they were remarrying, I said to her, “What on earth is going on?” And she said to me, in all seriousness, “Sometimes the devil you know is better than the devil you don’t.” I said, “That’s not a reason to marry!” “I dearly love him”, “I can’t live without him” – any of those things would have been understandable, but not “the devil I know”. I felt she was making a terrible mistake.’

Lana had relationship problems of her own. Pushed by her mother to follow in Natalie’s footsteps, she earned her first film credit at the age of nine, in John Ford’s epic western The Searchers, which starred John Wayne as well as Natalie. Lana played the younger version of her sister’s character. She would go on to feature in numerous films and TV series, most famously playing Plenty O’Toole in the 1971 James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever. At 16, she married for the first time; the marriage was annulled after a few months when her husband started hitting her. She would marry five more times over the next 17 years.

‘I was living in a very narrow world,’ she says. ‘The only people I knew were Natalie’s friends or people I would meet on a set. I don’t want to trivialise it, but it was almost like hanging out at a store that’s got everything on sale, and you didn’t really like anything to begin with but you started picking out the things that were the best of what there was. And I wanted so desperately to have a family unit of my own – just mine.

‘I can’t say I fell madly in love with anybody, but at the time they gave me something that I thought would work. But I also never thought, you’ve made your bed, now you can lie in it. I always thought, if you’ve made your bed and you don’t like it, you can get up and leave and try elsewhere.

Throughout her own difficulties, Natalie, Lana says, remained her ‘best friend’. They would go shopping together, have lunch and gossip. She lived with Natalie in her house in Malibu after her separation from Richard Gregson. ‘She was my defender and someone I loved being with. And she could be silly when she was with me, which was terrific for her; she needed that. We both gave to each other.’

Lana’s relationship with Wagner was more problematic. ‘He wasn’t someone I related to. And he had that kind of charisma and behaviour – “That was RJ!” – and I didn’t step too close. I involved myself only with Natalie. Plus the fact that he really looked upon me as a loose cannon, because I was in the habit of saying what I thought at all times, with most everyone. And that, I feel, kept him a little unnerved.’ She would only see Wagner when she visited Natalie, and even then they barely spoke.

And then Natalie died.

The weather conditions over Thanksgiving weekend were chilly, with rough seas. On the night of Natalie’s death, she, Wagner, Walken and the boat’s skipper, Dennis Davern, had gone ashore for what was later reported to be an inebriated and bad-tempered dinner. Back on the boat there was an argument between Natalie and Wagner, supposedly over her spending too much time working, away from the family and children. According to the account Wagner later gave to the police, Natalie went to the couple’s stateroom. Later, when he went to find her, she had vanished. The boat’s dinghy had also vanished. It was later found near Natalie’s body. The key was in the ignition, the gear in neutral and the oars tied down. It had evidently not been used.

When Natalie’s body was pulled from the water, she was wearing a flannel nightgown, woollen socks and a red down jacket.

The coroner concluded that Natalie, for whatever reason, had gone on deck, untied the dinghy and tried to step into it, but tripped and fallen into the water. There was ‘superficial’ bruising on her body and abrasions were found on her face, though ‘foul play is not suspected at this time’.

Less than two weeks after her death, the police investigation was closed, with the conclusion of ‘accidental drowning’.

The first Lana heard of her sister’s death was on the radio. Wagner had not contacted her personally, and she did not speak to him until the funeral. ‘It was an accident,’ he told her. ‘You’ve got to believe me, please believe me.’ She says that when she pressed him for an explanation someone took her arm and steered her away, telling her to leave Wagner alone.

For years, Lana says, she struggled to put the death of her sister to the back of her mind. The official version of what had happened was, she believed, absurd. Natalie had a lifelong fear of drowning and was a poor swimmer; she would never have tried to get into a dinghy in rough seas.

Nor could Lana make sense of Wagner’s behaviour following Natalie’s disappearance. He and Walken were helicoptered to land, and it was left to Dennis Davern to identify Natalie’s body. ‘Not identifying her body!’ Lana’s voice rises in anger. ‘I sat with my cat in the street when a neighbour accidentally killed it! So no, I cannot understand that.’ But she found it impossible to entertain the possibility that Wagner could have been in any way responsible for her sister’s death.

‘I was in denial to such an extent that I’d gotten tired of treading that water. There was so much going on in my personal life that to have to consider that someone that Natalie loved and was married to, that I had known since the age of eight, would have done something like that, was just completely devastating. I didn’t want to believe it, so I accepted it by keeping my mouth shut.’

Her attempts to talk to Wagner, she says, were always rebuffed. Her acting work had begun to dry up in the late 1970s and she worked in movie production. Then those jobs stopped too.

She found work as a sales executive for a telephone company, then in a department store and collectible-doll shop. She struggled as a single mother to her only child – a daughter, Evan, from her marriage to the actor Richard Smedley. When Evan married at the age of 18, her new husband moved into the small house where they were living.

In 1992, Lana received the first in what would be a series of telephone calls from Davern. In the aftermath of Natalie’s death, Splendour’s skipper corroborated Wagner’s account of what had happened. For a long time afterwards he lived at Wagner’s house, and Wagner found him the odd acting job, until he finally left and then moved to Florida. But it appears that his conscience had been troubling him.

‘He said there was a fight, Natalie was thrown down. And I’d say, “What happened, Dennis?” and he’d say, “I can’t tell you, but it’s terrible.” And then he’d hang up. Time would go by and he’d call back. And he was always incredibly torn and upset.’

Davern is not the ideal witness. Over the years he has drip-fed parts of his account to American tabloid newspapers and television shows, and in a book, Goodbye Natalie, Goodbye Splendour, with Marti Rulli, published in 2009. But his version of events, according to Lana, is this: from the get-go, Wagner was unhappy that Natalie had invited Walken to join them for the weekend on the boat. After returning from a ‘tense’ dinner ashore, Wagner snapped, smashing a wine bottle on the table and shouting at Walken, ‘Do you want to f—k my wife, is that what you want?’

Walken retreated to his cabin for the rest of the night. Natalie fled to the master stateroom. Wagner followed. Davern heard shouting and banging coming from the room. At around 11 o’clock the argument moved to the back deck, so loud that Davern turned up the radio to drown out the noise lest it be heard by people on boats moored nearby.

When he next saw Wagner, he has said that the actor looked ‘sweaty, flushed, anxious, nervous and dishevelled’. Wagner said, ‘Natalie is missing,’ and ordered Davern to search the boat. When the skipper returned to the wheelhouse, Wagner joined him and told him the dinghy was missing. Davern reached to turn on the searchlight and radio for help, but Wagner, pouring another drink for Davern, ordered him not to, telling him that drawing attention to the situation ‘might tarnish his image’. It took another two hours for Davern to convince Wagner to call for help. It wasn’t until 1.30am that the local harbour master was notified that Natalie was gone, and 3.30am that the Coast Guard was informed.

Wagner’s recollection of the evening is different.

In a 1986 biography, Heart to Heart with Robert Wagner, he described how on that fateful night he and Walken had got into ‘a political debate’, with ‘no fight, no anger. Just a lot of words thrown around like you hear in most political discussions.’ Natalie, ‘bored’, had left them to it. ‘We sat there talking for almost another hour. Then I went to kiss her good night, and found her missing.’

In another book, Pieces of My Heart, published in 2008, he changed his story, saying the argument with Walken was over Natalie’s career. The last time he saw her, he wrote, she was doing her hair in the bathroom. ‘The bottom line,’ he wrote, is that after that, ‘nobody knows exactly what happened…

‘Did I blame myself? If I had been there, I could have done something. But I wasn’t there. I didn’t see her.’

In 2011, 30 years after Natalie’s death, Lana joined a campaign to raise a petition calling on the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD) to reopen the investigation. The following year a supplemental autopsy changed the cause of Natalie’s death from accidental drowning to ‘drowning and other undetermined factors’.

In the course of her quest for the truth, Lana was introduced to a retired Los Angeles Police Department detective, whom she identifies only as Frank, who went back over the original autopsy report, pausing on the note that showed Natalie’s bladder contained 300cc of urine – a lot for a woman of her build. The shock of falling into cold water should have caused her bladder to empty, but it was full when her body was discovered. The cause of death was drowning, but it was possible, Frank theorised, that she could have been unconscious before she hit the water.

In February 2018, six years after reopening the case, the LASD announced that in the course of its investigations new evidence had emerged that had led police to reclassify Wood’s death as ‘suspicious’. Davern had been interviewed again and new witnesses who had been moored close to Splendour claimed to have heard an argument between Wagner and Natalie around the time of her disappearance. According to the lead detective, Lieutenant John Corina, because the case was not a murder investigation, Wagner was not a suspect, but ‘a person of interest’. He declined to be interviewed for the new investigation. According to Lana, two detectives investigating the case told her they had visited Wagner’s house and rung the doorbell, but been refused entry.

‘You’d think he had something to hide, wouldn’t you?’ she says. ‘Anybody who had witnessed or somehow been involved in something where someone was hurt or killed would say, “Let me help,” and, “This is what happened.” Turn on the searchlight! Call Baywatch immediately! Not sit there for two hours and get drunk. Or more drunk, I should say. It blatantly reeks of guilt to me.’

Lana’s own unsubstantiated theory about what happened that night is documented in her new book. She believes that following the argument with Walken, Wagner stormed down to Natalie’s and his stateroom. A furious argument ensued. Natalie fled to the deck, Wagner following behind. The argument continued, culminating in Wagner delivering a blow to her face and knocking her down. Panic-stricken, he threw Natalie into the water. Everything he did afterwards, Lana writes, was to cover up the fact ‘that in a drunken, jealous, rage-filled moment, he’d ended the life of Natalie Wood’.

The last time Lana spoke to Wagner was in 1998, when she summoned the nerve to call him to tell him Natalie’s mother had died. ‘I’m sorry,’ Wagner said, and hung up. The next day he rang back to ask if she was OK before quickly ending the call.

Wagner is now 91. He has always denied any responsibility for Natalie’s death. Last year he appeared in a documentary, Natalie Wood: What Remains Behind, produced by Natasha Gregson Wagner (Natalie’s daughter with Richard Gregson, who was mostly raised by Wagner). In it, they sought to banish what she called the ‘nonsense’ that Wagner may have been responsible.

Speaking to his stepdaughter, Wagner described enjoying ‘a few glasses of vino’ while talking with Natalie about her career and the time she was spending away from home. After she went to bed, Wagner opened another bottle of wine and started to argue with Walken, ‘smashing a wine bottle’, when Walken suggested Natalie should keep on acting. Walken retired. Wagner then went downstairs, discovered that Wood was missing, and notified the Coast Guard.

When authorities later told him that Wood’s body had been found, ‘everything just went out from under me’, he said. ‘We were all stunned, everybody. That night’s gone through my mind so many times. You can imagine.’

Lana was invited to appear in the film, but declined. ‘The entire thing is an attempt at whitewashing,’ she says.

Christopher Walken’s account of events has remained consistent over the years. Returning to the boat after dinner, he and Wagner got into the argument over Natalie’s career, following which he retired to his stateroom to sleep. After police reopened their investigation they stated that Walken was not a person of interest in the case.

In the years since, Lana’s own life has not been easy. Her daughter Evan was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and became addicted to opioids. In 2017, she died of a heart attack. Lana raised her three grandchildren, who are now 17, 21 and 23. But in recent years she has revived her acting career, playing small roles in independent films.

Closure, she says, is not a word she likes. ‘What I want would be if RJ could find the courage to just tell the truth. I would like him to be strong enough to say, “This is what I did, and I regret it, down to my soul.”’ She pauses, then repeats herself. ‘You know it was Dennis who identified Natalie’s body?’ She sighs. ‘So much, so much… Every time I talk about it I get wound up again.’

So no closure – no.

‘I would like justice for Natalie, but I know that’s not going to happen. But at least with this book I can clear the air.’

She pauses. ‘The one person that Natalie trusted… it eats at me. It really does. I don’t want to come off as vindictive or anything but… sometimes I am.’ She laughs. ‘There, that took care of that.’

Little Sister: My Investigation into the Mysterious Death of Natalie Wood, by Lana Wood, is out now (Dey Street Books, £20)