Rudolph Valentino’s Valentine: how Natacha Rambova became Hollywood’s greatest lover

When 25-year-old Natacha Rambova was interviewed by the film magazine Photoplay in December 1922, the celebrated costume designer was surely thinking of her own secret love affair with Rudolph Valentino when she discussed Hollywood’s celebrity circus. “Fame is like a giant X-ray,” she once said. “Once you are exposed beneath it, the very beatings of your heart are shown to a gaping world.”

Rambova had a stormy, controversial life. Along with her short, turbulent marriage to silent film legend Valentino, she survived a gun attack from a crazed lover, had bitter rows with film studio bosses, dabbled in the occult, got caught up in the Spanish Civil War and became an expert on Egyptology. The national publicity she received as a glamour icon of the 1920s brought its own intrusive focus on the sexuality of the woman born Winifred Kimball Shaughnessy on January 19 1897 in Salt Lake City. She certainly came to know the price of living before a gawping public.

The earliest sign of her individuality appeared in the incongruous setting of Leatherhead. Rambova was sent to a small English boarding school at the age of 11, a decision that came after her mother left Michael Shaughnessy – a violent drunk and bankrupt gambler – to socially upgrade by marrying Edgar de Wolfe, brother of famous interior designer Elsie de Wolfe. It was Elsie who nicknamed the girl ‘Wink’ to distinguish her from her mother, also called Winifred.

Rambova’s time in Surrey was unhappy and she longed for her summer vacations in Paris. She disliked the sterile environment, hated the games of Lacrosse, and clashed with teachers. She was eventually expelled for “conduct unbecoming of a lady”. She later said that her happiest moments at Leatherhead Court School were those spent studying mythology. Although her family thought her rebellious, an oil painting of the young teenager, executed in Paris by Robert Lee MacCameron soon after her departure from England, seems designed to suggest a sweet-natured youngster. The portrait was considered for display by the Louvre.

In 1914, determined to be a professional ballerina, 17-year-old Winifred left France for New York to study with Theodore Kosloff’s Imperial Russian Ballet Company, a troupe she had seen in London a few years earlier. It was 32-year-old choreographer Kosloff, a man known for his open philandering with ballet girls, who persuaded the teenager to change her name to Natacha Rambova (that of a former girlfriend) and, with his wife and baby still in Europe, he began a tempestuous affair with the teenager.

Natacha’s mother tried everything she could to get her daughter out of his clutches. She withheld $2,000 in payments for dance lessons and gowns, and in the subsequent court battle insisted she would pay if Kosloff stopped seeing her daughter – then tried to have him arrested and deported on statutory rape charges. In June 1916, fearing her relationship with Kosloff was about to be torn apart, Rambova fled to Canada. Newspapers in New York reported on the “the strange disappearance of Winifred de Wolfe”, detailing that her mother had hired a “flock of private detectives” to track down the 19-year-old.

She finally turned up in Europe, pretending to be the governess to Kosloff’s child. Winifred’s mother eventually withdrew kidnap charges and allowed her daughter to return to America to live with the Russian in Los Angeles. Rambova, who at 5’ 8” was considered too tall to be a lead ballerina, began to excel at making costumes and set designs, although for a long time Kosloff took false credit around Hollywood for her sumptuous work.

One night, after confronting him about his infidelities with other young ballerinas, Rambova packed her bags and ordered a taxi. Kosloff picked up his birdshot hunting rifle and blasted her at close range in the leg. Bleeding and screaming, she jumped through the window of their Franklin Avenue home and escaped, finding a friend who removed the shotgun shells and patched up her wounds. Drake Stutesman, Professor in Cinema at New York University, believes that Kosloff was undoubtedly “trying to kill her”. Even that wasn’t enough to make her leave him permanently and their strange, manipulative affair dragged on for several more months.

1920 was a breakthrough year for Rambova. Finally free of Kosloff, she was formally adopted by her new stepfather Richard Hudnut, a millionaire perfume tycoon, and she also began working for Cecil B. DeMille, creating the costumes and décor for his films Why Change Your Wife? and Something to Think About. In 1920, she also began a fruitful relationship with Russian Broadway star turned film director Alla Nazimova, for whom she designed costumes for Billions, following up in 1921 with work on Camille and the unfinished Aphrodite. Rambova was at last financially independent, earning $5,000 a picture (equivalent to approximately $70,000 today)

In early 1921, Rambova met Valentino on the set of Uncharted Seas, a silent film that is now lost. She initially thought he was “dumb”, adding that, “it wasn’t love at first sight. I think it was good comradeship more than anything else.” In a later memoir, she recalled that he was wearing a fur coat when he “advanced and shook hands,” describing his grip as “a little too firm for comfort”.

At the time, Valentino was still stuck in what was known at the time as a “lavender marriage”, this one designed to conceal the sexual orientation of his lesbian wife Jane Acker. Valentino’s marriage to an actress three years his senior was never consummated. The Italian-born actor, whose reputation was growing after the success of The Sheik, had also been an unruly child, and he bonded quickly with Rambova, as they discovered a mutual love of art, clothing and animals.

They began living surreptitiously at a bungalow Rambova rented on 6612 Sunset Boulevard, a one-bedroom home that, incredibly, they shared with two Great Danes, a large gopher snake, a green monkey and a lion cub named Zela. The neighbours apparently made regular complaints about the lion cub’s escapes. Zela even bit the leg of a stranger who visited the bungalow, something that came to light only because the man was a private eye hired by Acker to prove Valentino and Rambova were co-habiting.

The lion cub was eventually returned to a trainer and the lovers settled for a Doberman Pinscher and three Pekinese as replacements. These were among the couple’s happiest days. “We were both poor, still unknown to the world in general, and glorying in our freedom. They were days of laughter, days of dreams, and of ambitious planning for the future,” she recalled.

In March 1922, Valentino began divorce proceedings. He made the foolish decision to wed Rambova without waiting for the required one-year period to elapse under Californian annulment laws. When Rambova became Valentino’s second wife in May that year, Acker sued for the legal right to call herself “Mrs Rudolph Valentino” and subpoenaed witnesses who had been at the wedding in Mexico. The authorities arrested the actor, and he was sent to jail in Los Angeles for bigamy. After he was released, he agreed to live apart from Rambova until his divorce was finally concluded. They married for a second time, tying the knot in Crown Point, Indiana, on March 23 1923.

In a newspaper interview, Rambova talked about her choice of names. “Whether to call myself Winifred Hudnut or Natacha Rambova or Mrs Rodolph Valentino, I don’t know. Natacha Rambova seems to belong most to me, the individual I think I am, but of course, I wasn’t born that way. When I went into the Russian Ballet, though, I had to have a Russian name. That was just after my course at art school in Paris and I was 17, and I have been using that name ever since. I speak Russian and all that is Russian appeals to me and moreover that is what Rudy calls me.”

In his famously controversial book Hollywood Babylon, Kenneth Anger claimed that Valentino had regular male lovers at the time and said there was doubt over whether he ever actually slept with the “butch” Rambova (a description wholly at odds with Yugoslav Paul Joanowitch’s 1925 oil portrait of the elegant, stylish designer). However, according to Emily Leider’s 2003 biography Dark Lover: The Life and Death of Rudolph Valentino, cinematographer Paul Ivano, who sometimes slept on the living-room couch at the notorious lion cub bungalow, claimed that he once saw the young lovers having such passionate sex that Rambova passed out.

There has been perhaps an overly prurient interest in Rambova’s sexual orientation, although it is worth noting that her bisexuality is mentioned in the books Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to World War II and Lesbian Lists: A Look at Lesbian Culture, History, and Personalities, in reference to her affair with Nazimova. (Acker also slept with the Russian woman, but bed-hopping between genders was nothing unusual in Hollywood in the 1920s.)

In June 2019, a one-hour documentary called Behind the Shadow of Natacha Rambova was aired at the Atlàntida Film Festival in Majorca. “That gossip of bisexuality arose when she began working with filmmaker Alla Nazimova,” the film’s writer and director Georgina Sas tells me. “These two very talented and modern women were just two lesbians who were entertained by smoking opium during their free time and at parties. The two managed to form an effective and brilliant women’s team in a male-dominated industry. Rambova was a cultured, restless, independent woman, sensitive and advanced for her time.”

Rambova and Nazimova’s greatest collaboration came in the year of her marriage, when Valentino’s second wife designed the costumes and sets for a visually stunning adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s one-act play Salomé. The highly stylized costumes, inspired by the illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley, included cinema’s first micro-mini skirt as Nazimova performed a dance of the seven veils accompanied by chorus girls in large shoulder pads. Despite its reputation as a seminal art film of the silent era, Salomé was a financial disaster for Nazimova.

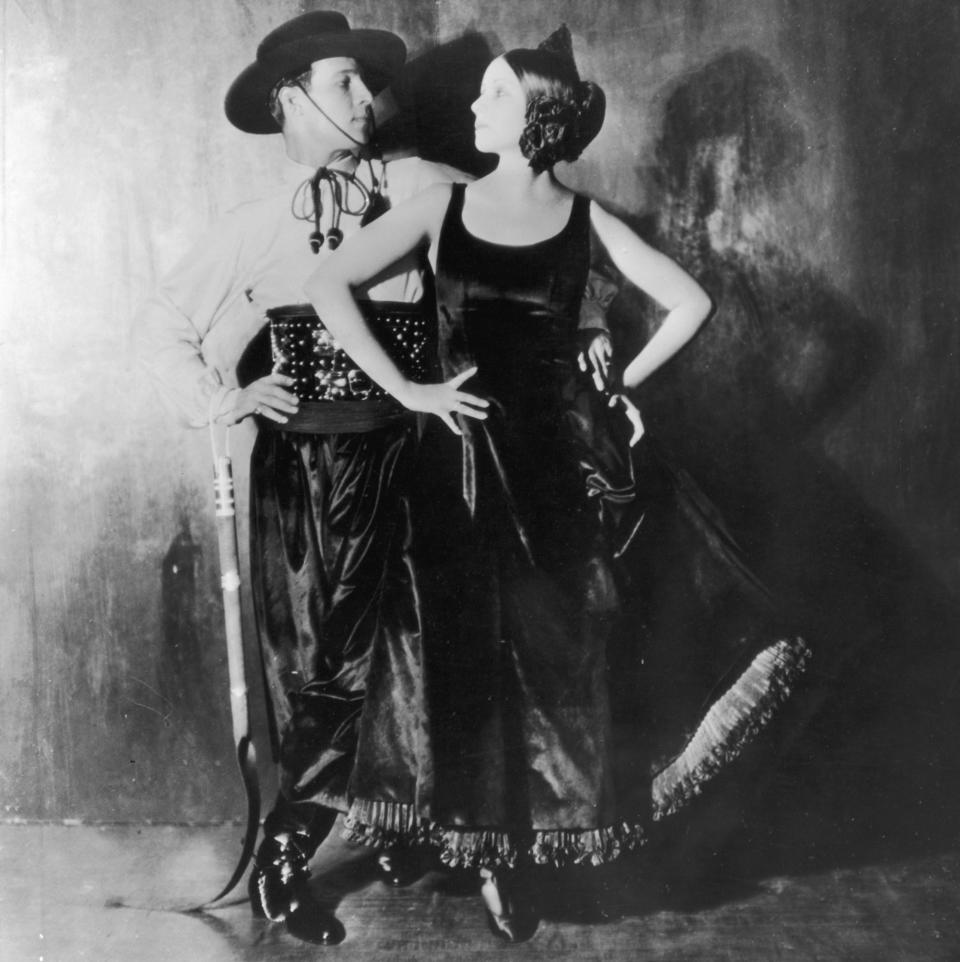

But it was Rambova’s partnership with Valentino that made her famous. They worked on seven films together, including Beyond the Rock and A Sainted Devil, during which time she masterminded his career, shrewdly negotiating his contracts to get improved deals for a man who’d regularly been in debt. They bought an eight-room house in Whitley Heights, Hollywood, and purchased custom-made cars.

Rambova designed the extravagant historical costume for Valentino in the critically acclaimed French drama Monsieur Beaucaire, but his fans were turned off by the sight of the famous “Latin Lover” in powdered 18th-century wigs and dressed in opulent frills. There were complaints that the woman dubbed “Nasty Rambova” was ruining America’s first male sex symbol. The platinum slave bracelet she gave him, jewellery that stayed on his wrist day and night, only confirmed the prejudices of her detractors. “I’ve been called everything from Messalina to a dope fiend,” she admitted to actress and dancer Myrna Loy.

In March 1925, Variety ran a front-page story headlined “Mrs. Valentino Cause of Break with Williams,” reporting disagreements between the Valentinos and Ritz-Carlton Pictures boss James Dixon Williams. It came after Valentino tried to make The Hooded Falcon, a film for which Rambova wrote the script. Excessive spending caused Ritz-Carlton Pictures to halt production on this passion project and the movie was never made.

After Valentino ditched both Ritz-Carlton and Paramount to sign with United Artists in May that year, a persistent rumour started that Valentino’s new contract specifically forbade Rambova from being on set with her husband. When her 1927 book Rudolph Valentino: A Wife’s Memories of an Icon was reprinted in 2015 by Theodosia Tramp Publishing, editor Hala Pickford denied there had been any truth in the rumours. “She is not mentioned in the United Artist contract, nor was she ever formally ‘banned’ from the set,” Pickford wrote in the foreword.

Nevertheless, she was frozen out by United Artists and she gradually lost the ability to curate his artistic vision. At the same time, their personal life began to unravel. Rambova, a pioneering early Hollywood feminist, insisted she wanted to continue working: “I won’t be a parasite. I won’t sit home and twiddle my fingers, waiting for a husband who goes on the lot at 5:00 a.m. and gets home at midnight and receives mail from girls in Oshkosh and Kalamazoo…. he knew what I was when I married him.

“I have been working since I was 17. Homes and babies are all very nice, but you can’t have them and a career as well. I intended, and intend, to have a career and Valentino knew it. If he wants a housewife, he’ll have to look again,” she said. The reported rift over having children was a central scene in the 1975 movie The Legend of Valentino, written and directed by Melville Shavelson, in which Rambova, played by Yvette Mimieux, tells her husband: “I’m an artist. I wasn’t made to have babies.”

His contract with United Artists did nothing to stem the jokes around Hollywood about Valentino being his wife’s “clothes horse”. The actor, who enjoyed wearing outlandish fur coats, colourful cravats and any one of his 110 silk handkerchiefs, was still manicured by Rambova, who often applied lipstick and shadow to his eyelids before she “fluffed his locks with curling irons”. All this grooming made Valentino the target of an anonymous homophobic editorial in the Chicago Tribune, headlined ‘Pink Powder Puffs’, which blamed Valentino for the presence of powder vending machines in the city’s men’s rooms.

By the time Rambova was handed an acting role alongside Loy in the silent picture What Price Beauty?, a film she co-wrote and co-produced, her marriage was on the point of acrimonious collapse. Even the Valentinos’ shared interest in attending seances was not enough to save a marriage from an early grave. When Rambova left LA for New York in August 1925 it was the last time she ever saw him. Valentino moved into a Beverly Hills mansion called Falcon Lair (named after a time he and Rambova had hatched a bizarre plan to train falcons) and awaited the divorce papers. They were filed in December 1925.

Valentino was dead within eight months. Although there were rumours that he’d been poisoned with arsenic after ditching a New York society mistress, or that he’d died from the complications of syphilis, it was in fact pleurisy and peritonitis, complications that followed an operation at New York’s Polyclinic Hospital for a ruptured appendicitis and perforated gastric ulcers, that caused his death on August 23 1926. It’s a dismal thought that he died worrying about his masculinity: his first words after waking from surgery were, “did I behave like a pink powder puff or like a man?”. In his will, the 31-year-old left Rambova just a single dollar bill from his one-million-dollar estate.

Rambova, who was holidaying in the C?te d’Azur when she received a telegram about his death, was unable to attend Valentino’s funeral; his business manager ignored her odd request that he should be buried in her family crypt. “She was devastated,” Stutesman told Sas, and inconsolable to the point that she locked herself in her French Riviera bedroom for three days. Valentino’s funeral, attended by 100,000 people, was a chaotic, farcical affair. There were more than 100 injuries and reports that two of his female fans attempted suicide. In a twisted publicity stunt, the New York funeral home hired four men in Blackshirts to stand as guards of honour, pretending that they had been sent by fascist leader Benito Mussolini.

Shortly after Valentino’s death, Rambova became deeply interested in theosophy and occultism. With public opinion against her, she published the memoir Rudy: An Intimate Portrait of Rudolph Valentino By His Wife, Natacha Rambova, which condemned Hollywood as “a golden hell”. She said that only those “ready to accept the truth” should read a book in which she explained her communications with her late husband, which she published as messages purported to have come from the astral plane, taken down in automatic writing (also known as psychography) while she was in a trance-like state. (Rambova’s occult powers were later deployed to terrifying effect by Ryan Murphy in his TV series American Horror Story: Hotel, in which she’s reimagined as an immortal Golden Age vampire.)

After her next acting foray failed – she was panned for her part in the lost 1926 silent film When Love Grows Cold, with Picture Play magazine describing it as “the poorest picture of the month, or of almost any month, for that matter,” and singling out Rambova for her poor performance – she scratched around for other projects. She designed and patented a doll, appeared in vaudeville, and opened a chic clothing salon in New York, featuring her original designs.

In 1928, she wrote a three-act play called All That Glitters, based on her experiences in Hollywood. Although the play was never produced, the rights were retained by the Rudolph Valentino Society and a version was published in 2015. The drama is set in the Coliseum Theatre, where Henry Warwick (the character based on Valentino) is the head usherette. Henry’s wife Alice was based on her own character. Their marriage is portrayed as fractious. “There you go pouring cold water on my ambitions again,” Alice says at one point.

That same year a legacy from her stepfather Hudnut, who died in Paris, gave Rambova some financial security. She shut her shop and used the money to relocate to Europe, settling down in a village just outside Palma, Majorca. She became a popular figure on the island, known for her fast driving, wild parties and her love of Abdulla cigarettes. Rambova, who spoke fluent Spanish (and French and Italian) made extra money buying and selling works of art.

She fell for a Spanish aristocrat called Don álvaro de Urzáiz, whom she married in 1932, at the age of 35. For several happy years they ran a business restoring Majorcan villas for tourists and running guided tours of Genova Caves. According to filmmaker Sas, there is a villa in Peguera called Can Na Tacha “which she designed herself and which remains intact, owned by a Spanish marquise.” Sas’s documentary reveals that Rambova was still indulging in spiritualism while she lived there. There is an amusing anecdote about the time she supposedly received a message from beyond from Valentino to inform her that they played “a lot of jazz” in heaven.

It was during her marriage to Urzáiz that Rambova first travelled to Egypt. In 1936, she visited Menefer, Luxor and Thebes and was entranced by the experience. “The first few days I was there I couldn’t stop the tears streaming from my eyes. It was not sadness, but some emotional impact from the past – a returning to a place once loved after too long a time,” she recalled.

Soon afterwards, she left de Urzáiz in a dispute over the Spanish Civil War. She was appalled by the brutal executions of Republicans by Franco’s Nationalist forces – she took photographs of the aftermath of their invasion of the island and publicly upbraided the bishop of Majorca for his lack of courage – that she left for France, while her husband eventually became a naval officer for Franco’s fascist forces. The Majorca Daily Bulletin newspaper even speculated that she was spying for the British, having been recruited by Captain Alan Hugh Hillgarth, an intelligence officer who was close to Winston Churchill and who was working as British consul on the island at the time. It’s yet another mystery in a life of intrigue.

She cancelled her first attempt at leaving France in 1939 when staff on the SS Manhattan refused to allow her Pekinese dog in the cabin with her, but escaped soon afterwards when it was clear that the Nazis planned to invade France. Finally back in America, she began to find a meaningful life for herself by devoting herself to the study of ancient religion, astrology, symbolism and Egyptology.

Although she still maintained some of her stranger fads – including her belief in the Lost City of Atlantis and her theory that “excitable” men could calm themselves by lining their hats with green or blue cloth – her dedication to the study of Egyptology impressed experts such as Stephen Glanville at University College London and Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung.

In the early 1940s, she wrote articles for American Astrology that were well received. Michael Morris, a lecturer at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California, and author of the 1991 book Madame Valentino: The Many Lives of Natacha Rambova, said: “She incorporated into her argument a remarkable knowledge of varied fields, including physics, metaphysics, symbology, cosmology, alchemy, mythology, and numerology.” Some of the Egyptology periodicals she compiled (and raised funding to publish) are still considered vital texts.

Later, she obtained a Mellon Grant and regularly travelled back to Egypt to study symbolism and belief systems, later donating her extensive collection of Egyptian artifacts to the University of Utah’s Museum of Fine Arts. Her previous life was not something she shared with academics, and she never talked in public about Valentino. Indeed, in 1951 she threatened to sue Columbia Pictures if they portrayed her in a biographical film released about her first husband, who was played by Anthony Dexter.

She kept up her academic work in the 1950s despite struggling with the autoimmune disease scleroderma, something that may have been brought on by the anorexia she suffered from throughout her life. As the effects of the disease worsened (she found it difficult to swallow) her mental health went downhill. Morris’s biography recounts that she became delusional, believing that she was being poisoned, and ceased eating. In September 1965, she was discovered going “berserk” in a hotel elevator in Manhattan and was subsequently admitted to Lenox Hill Hospital, where the 68-year-old was diagnosed with paranoid psychosis brought on by malnutrition.

Her cousin Ann Wollen intervened and moved her from New Milford, Connecticut, where she’d lived with two Yorkshire Terriers, to join them in Pasadena, California. When her health declined further, Rambova was admitted to a local nursing home, where she died of a heart attack on June 5 1966, aged 69.

Near the end of such a remarkable, action-packed life, Rambova lamented that one of her dearest wishes – “the fast vanishing dream to someday start a small museum of religious symbolism” – went unfulfilled. Even so, she left an estate worth $368,000, a huge collection of Tibetan-Lamaist art and ritual objects (which she donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art) and an unfinished 1000-page manuscript on patterns within the texts in the Pyramid of Unas.

Following her expressed wishes, Rambova was cremated without a service and her ashes were scattered in a forest in northern Arizona, far from the gaze of public attention.