Simple Minds: ‘Everybody shouts about our first five albums, but no one bought them’

David Bowie said you’ve got to be dysfunctional to be an artist,” says Jim Kerr. “That chimed with me. The idea that you would risk everything to express yourself – och, you’ve probably got to be on a spectrum somewhere. But what is the alternative if you’re that way?”

The 64-year-old frontman for Simple Minds has been reflecting on a lifetime in music, which is celebrated in a new documentary, Everything Is Possible. “Self-analysis doesn’t come natural to us,” says Kerr, gesturing towards lifelong friend and bandmate Charlie Burchill, also 64. “Where we’re from, it’s about pragmatism, and just getting on with it. But at the same time, we’re very keen to eke out the best of the last 20 minutes of the game.”

His football analogy is not just a reference to the lifespan of his band. “I mean, the game! The same game we’re all in! If you were young and obsessed with looking back or caught up in nostalgia, you’d be deemed pathetic. But at our age, you want to try and make sense of it all.”

Kerr and Burchill met in a pile of worker’s sand, on the first day their families moved into a new tower block estate in Glasgow, in 1967, when they were about eight years old. They attended the same school, became rock music fans together, seeing gigs by David Bowie, Roxy Music, Lou Reed, Bob Marley and The Who at the Glasgow Apollo. In 1977, they formed a punk band, Johnny & the Self Abusers, and released one single, Saints and Sinners. Influenced by Kraftwerk and other electronic bands they discovered while hitchhiking across Europe as adventurous teenagers, they reshaped the group into Simple Minds, named after a lyric in Bowie’s The Jean Genie. They performed their first gig in January 1978.

“It was a freezing Tuesday night in Glasgow, supporting Steel Pulse, and we walked out to the sound of our own feet and went down a storm,” purrs Kerr in his burry Glaswegian accent. “I remember the first song started out with this riff Charlie came up with, and I looked across, and I knew he was going places, so I thought I better hitch my wagon to his, and we can go together.”

The then 18-year-old Kerr did an interview with a local paper afterwards, in which he stated that their ambitions were to “become a great live band”, “see the world” and “get a life out of it.” Forty-six years later, “that’s still the aim, that’s still the challenge”.

Kerr and Burchill are very engaging company, frequently laughing at each other’s comments and amending each other’s sentences, with Burchill the more straightforward and sincere, while Kerr can be teasingly humorous but also more philosophical. “Sometimes you’re just lucky, you meet people and you get along, you bring something that complements the other, you don’t challenge each other’s space. But yeah, it’s a bit of a mystery, even to us.”

“In our relationship, Jim’s the big brother,” says Burchill. “That was always really clear, since we were very young. I’ve always felt lucky to be guided by Jim.”

Yet in Simple Minds that occurs in an area where Kerr proclaims wilful ignorance, even innocence. “I’ve never had the impulse to pick up an instrument,” says Kerr. “Music is magical to me, I’m in awe of musicians.”

Burchill is a gifted self-taught guitarist, who also plays saxophone and keyboards, and is constantly working on assembling pieces of music from riffs, chord sequences and sonic atmospheres. “Charlie is always doodling, and I just sit there. It’s almost like fishing, waiting for something to appear, and then I try and catch it and pull it to shore. Being the singer, you’re responsible for the bulls---. It’s up to you to come up with the myths and language of the band.”

“I can play the same three chords five times, and Jim’ll think it’s five different chords,” declares Burchill. “No, but they’re not just chords,” protests Kerr. “I hear a cityscape and there’s steam coming out, and there’s a lonely man in the corner! And Charlie’ll go, ‘It’s a f—ing G and an F, Jim!’”

Simple Minds started out making arty, left-field synth rock but, as the 1980s progressed, their sound swelled to stadium-level proportions. “Hardcore fans always talk to us about the first five albums – the cooler, blurrier, druggy art school ones that get all the acclaim”, says Kerr. “Apart from your bank manager who won’t give you a mortgage.”

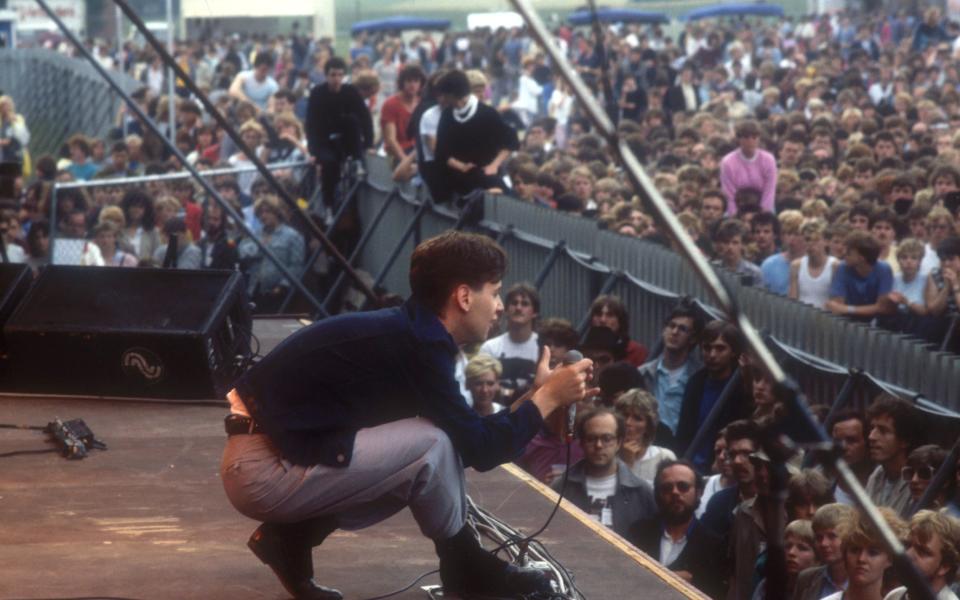

“Everybody shouts about them, but no c—s bought them,” adds Burchill. Then, as Kerr puts it, they “found a wee bit of focus”. They had a run of multimillion selling albums with New Gold Dream (1982), Sparkle in the Rain (1984), Once Upon a Time (1985) and Street Fighting Years (1989), and scored hits all around the world including Promised You a Miracle, Waterfront and Up on the Catwalk. They reached number one in America in 1985 with Don’t You (Forget About Me), the theme tune from The Breakfast Club. They headlined stadiums and played Live Aid, as well as Nelson Mandela’s 70th Birthday Tribute. Kerr had high-profile rock and roll marriages to the Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde – 1984 to 1990 – and actress Patsy Kensit – 1992 to 1996 – as well as a child with each.

There was a sense that they had sacrificed credibility, losing rock fans while discovering pop audiences could be more fickle. Original band members departed, and Kerr and Burchill struggled on to declining returns. “It didn’t feel good, that’s for sure. We were running on fumes in the 1990s,” admits Kerr. “You learn a lot about yourself when you’re in a van going to play a club that isn’t sold out, and you drive past a stadium that you did sell out. But what you gonna do, cry to your mammy? Or just get up and play?”

It is a point Kerr returns to, an insistence on an ethic drilled into him during a tough but loving working-class upbringing. “No one owes you anything. Better people than us went down, better people than us didn’t even get the chance to go up. One thing we knew was, you could stop being Simple Minds, but you can’t stop being Charlie Burchill, and you can’t stop being Jim Kerr. So we got up and played, and that has led us here.”

Some members of the 1980s Simple Minds line-up declined to take part in the documentary. “There’s hurt,” admits Kerr. “It’s not easy getting sacked, or maybe they just got sick of me. But they brought a ton to the music, and we’ve got nothing but love. It’s not for everyone, this life, going at it the way we’ve gone at it. People miss home comforts. Ten years is a long haul. But what you gonna do if you still feel like making music? Do you wanna be in the same room for 50 years with the exact same people, the exact same chat, the exact same feel? There’s a lot to be said for strapping on a new engine.”

And yet Burchill and Kerr have remained loyally together (“an old Scottish couple, joined at the hip”, laughs Kerr) continuing to make Simple Minds albums (there are 21 studio albums, with another in the works) and slowly rebuilding their audience (next year they embark on a world tour).

Curiously, the boys who grew up on the same street now both live in Taormina in Sicily, Italy (Kerr moved there 20 years ago, Burchill followed more recently). “Charlie and I had wanderlust as kids,” says Kerr, who lives with his partner of 20 years, a Japanese businesswoman called Yumi. “For some people, the world ends at the bottom of your street, for other people that’s where it begins. Simple Minds has been the lifeboat that has carried us all these years. This is who we are. It’s no mystery to me we’ve ended up at the bottom of a volcano! When the whole world goes to hell in a handcart, we’ll be found amongst the ashes, trying to get a G and an F!”

Simple Minds: Everything Is Possible will premiere on Dec 22 on Paramount+ UK. They tour the UK from March 15 next year; simpleminds.com