Sir Patrick Stewart on the 'Last View' of Captain Picard

In his new memoir Making It So, Sir Patrick Stewart delves into his own origin story, reflecting on the people, places and experiences that helped shape his extraordinary career. Alongside behind-the-scenes anecdotes from his years as a Shakespearean stage actor and his multiple stints as Star Trek’s Captain Picard, Stewart evocatively describes his working-class upbringing in a mining town in the north of England, his experience of growing up around domestic violence and how he found success against the odds in an industry that notoriously favors the privileged.

In a conversation with Parade, Stewart admits that he was hesitant about writing a memoir, although the suggestion had been floated many times over the years by his agent. “I knew it was going to take a lot of time, because I’m a slow reader and a slow writer,” he explains, adding that it was easy to keep putting the project off, because for the past several decades, Stewart has essentially never stopped working. But then came the pandemic. In the silence and stillness of 2020, taking the time to write no longer seemed so impossible. “When my agent suggested I give it a go, I said all right, on the condition that if I don’t like it after a couple of weeks, I’ll repay the advance that I received, and go back to my jigsaw puzzle.” But as it turned out, once he sat down to write, he had a lot to say.

Ahead, Stewart discusses the emotional process of telling his own story, how his approach to acting has changed over the years, and his hopes for one final Picard adventure.

Writing an autobiography is a huge undertaking, and you say you’d been daunted by the idea of it in the past. Where did you begin?

I sat here in my study, looking at the blank screen, and thinking about my childhood, and thinking about the dominant recollections that I had, and then one floated into my head with great clarity. It was the field, where we used to play soccer in the winter and cricket in the summer, where "bring and buy" sales were held, brass band concerts, and all that kind of thing. That’s where I began, and it all just unrolled from there.

I have a feeling it won’t ever unroll like that again, because most of what I put into that book, I’ve never talked about. A lot of it, either I didn’t remember or I was uncomfortable about it. And I had to get used to that sense of discomfort. But fundamentally, I was thrilled by it, and it was a very, very therapeutic experience. I think I got released from a lot of stuff I’d locked away.

I can imagine it being very cathartic to write out in that way.

It was. Even when I was recording the audiobook, there were moments when I couldn’t go on reading, because I was too moved and too upset. And after the second time that happened, Christina, my producer, said, “You know, I don’t think we should take that out. Let’s leave that silence there, where you can’t speak, and then go on.” So that’s what we’ve done, [embraced] that openness and frankness. I have, for the last thirty years or so, been very fortunate to have great therapy sessions. Just talking to someone about my life and my feelings, I think, was an invaluable part of being able to release memory, and release emotions.

Related: 50 Picard Quotes to 'Engage' Your Mind and Inspire You to Live Boldly, Bravely and Baldly

You write about how fortunate you feel to have grown up at a time when there was a lot of investment in the arts. You were able to get a grant to attend acting school, and as you note in the book, a lot of that type of funding no longer exists, which has led to a real class divide in the UK film industry.

Without the support of my local government, I would never have had a career. Because I left school at 15. I didn’t drop out or anything like that, it was just over. All my classmates were looking for jobs, and a lot of the men were going into mills or underground to the mines—coal mining was a big activity in my neighborhood. And women were going into weaving like my mother. When I auditioned for a place at the Bristol Old Vic theatre school, I was offered a place on the day. And when I went home that night, of course, my father said, “Well done, but who’s going to pay for it?” We didn’t have savings or anything; my parents’ money all went to keeping up the household and feeding my brother and myself.

But I was awarded a grant through my local council, West Riding County Council. It was a huge grant, and it paid for everything—my lodgings, my food, the books and clothing I had to buy, everything. That doesn’t exist any more. It’s gone. And I feel so sorry and so angry for young people who are wanting just to do what I did, and give it a shot, and they can’t. It’s a condemnation of our society.

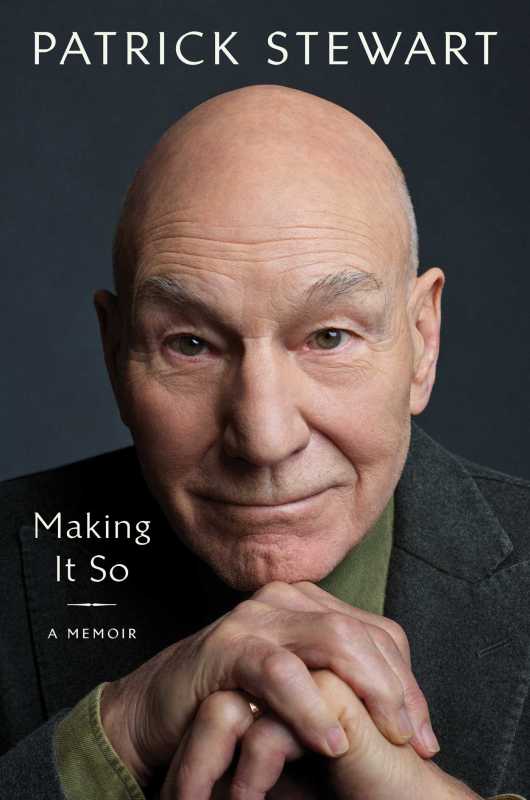

Simon & Schuster

You’re hoping to play Jean-Luc Picard one final time in a potential movie. Why does the big screen feel like the right place to wrap up his story?

In part, it’s because that’s how it has always been with Star Trek. The first Star Trek series with William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy, they almost tried to pull them off the air at the end of the first season, but they hung on, they did three seasons. And then the next thing they did, quite a lot of years later, was to make full-length feature films. With Picard, the transformation of the character from The Next Generation through to Star Trek: Picard was extreme, and in the process of making [the 2020 series], I was encouraged to look for the unexpected things that might happen to, or be done by, Jean-Luc Picard. And I think the only way we can acknowledge that, and give audiences what would certainly be their last view of Jean-Luc, would be to film [a movie] based on the three seasons of Star Trek: Picard.

Related: How to Watch Every 'Star Trek' Movie in Order

There’s an anecdote from the early Star Trek days where you describe getting frustrated with your co-stars because you felt like they were goofing around too much, and ended up yelling at them: “We’re not here to have fun!” You describe how you came to see this as a totally misguided lecture on your part. What changed?

One of the most important comments that was ever made to me was on the day that I worked with one of my heroes, Rod Steiger. I had a tiny scene with him one day [on the 1975 drama Hennessy], and hearing that it was my first time on camera, he invited me to his trailer for lunch. He allowed me to ask him a lot of questions, and he said to me, “Patrick, the one thing you have to remember is that the camera photographs thoughts.” That had never entered my head before. I thought it was all about verbalization, and maybe facial expression. But there could be none of that, and if you’re thinking and experiencing something, the camera still sees it. At first, I was taking it far too seriously, and not realizing that one can have fun, and enjoy something.

There was, I think, at the very beginning of film, not much difference between stage acting and film acting, and now, there has been a shift, especially in young actors. For example, the tonality of voice—actors are using a much softer tone today than they were on film when I first started. They’re also a little more emotionally open than I have been used to seeing, and I find that very potent. Often now, watching television, I’m registering, “That’s good work, I want to try that.”

That reminds me of the section of the book towards the end where you talk about how you have no interest in retiring, because there’s still so much that you want to do.

Yes, particularly having not acted for 18 months, which is the longest period I’ve ever gone. I love my work, sometimes to the abandonment of my family; I love my work so much, which I have paid a price for. But it is a job that fascinates me still, and there’s more that I want to experiment with.

Is there anything in particular you’re eager to do, when the industry starts up again?

Well, I’m curious as to what impact the book might have on the acting work that I do. I wonder if it’s going to lead me in one direction or another. Having spent two-and-a-half years writing a memoir, am I going to miss Patrick Stewart when I start my next acting job? Or, am I going to, based on what I experienced when I was writing the book, am I going to let more of Patrick Stewart bleed into the work that I do? I’m intrigued about that. I’m looking for an opportunity to infiltrate, to bleed into, the work that I do, more that has perhaps been shut up in me in the past, and that I’m now quite eager to release.