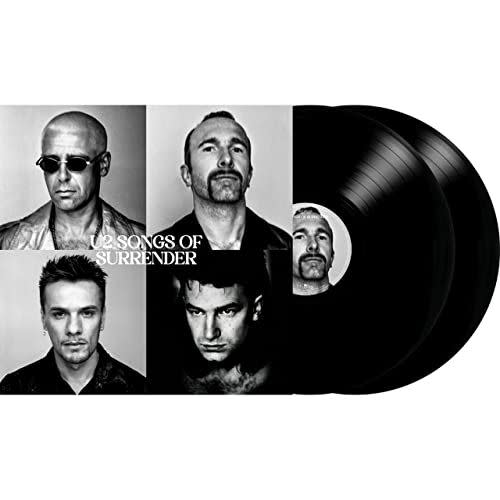

'Songs of Surrender' Puts U2's Songwriting Legacy on the Line

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

It has been said that you can measure the greatness of a song if it holds up accompanied by just a guitar or a piano. Which is true to a point—but also plays into the idea that music production is somehow cheating, that sonic treatments are there to cover up flaws, not serve as actual compositional tools.

If there’s one band whose body of work challenges this rule completely, though, it’s U2, who have always been defined by the totality of their expansive, atmospheric sound more than just their words and notes on a page. Consider the scene in the 2008 guitar documentary It Might Get Loud, when The Edge switches off all his pedals and effects—the rig that Bono once described to me as looking “like Cape Canaveral”—to show that the swaggering introduction to “Elevation” is actually just him plinking two simple chords.

But with their new collection Songs of Surrender, their first release in six years, Ireland’s Finest are taking that plunge, reinterpreting forty songs from their catalog with new arrangements that are mostly intimate and acoustic, and frequently replacing Edge’s electric arsenal with quiet keyboards. Inevitably, it’s a bit hit-or-miss, and likely not essential for those who aren’t superfans, but there are many pleasures and discoveries to be found.

There’s a grand tradition of rock stars stripping down or reworking their material, from Elvis in the boxing ring on the “comeback special” to the MTV Unplugged series to pretty much every time Bob Dylan steps on stage. But this sprawling set represents a big swing from a group that’s never been afraid to take big swings—a grand statement about a Hall of Fame band’s songwriting legacy. (Songs from almost all fourteen of their albums are included; nothing from 1981’s October or 2009’s No Line on the Horizon made the cut.)

It’s also part of a multi-year phase during which U2, which spent decades insistently focused on the future, has been looking back: They did a massive tour performing 1987’s The Joshua Tree album in full in 2017 and 2019, will soon be opening the new Sphere venue in Las Vegas with a show built around 1991’s Achtung Baby, and Bono recently published a best-selling memoir.

A confusing note: That book is titled Surrender and consists of forty chapters, each named for a U2 song, so one might reasonably expect that Songs of Surrender would contain those same forty songs. Not the case. Instead, a dozen of the selections differ. On the other hand, the first song of the package is “One” and the fortieth is “40”—well played, boys.

Songs of Surrender (which follows 2014’s Songs of Innocence and 2017’s Songs of Experience) was Edge’s lockdown project, and he’s the album’s primary producer, with assists from a few other folks, most notably Bob Ezrin, whose credits include KISS, Alice Cooper, and Pink Floyd’s The Wall. He took the task seriously, crafting thoughtful new ways into these compositions, not just campfire singalongs. In the liner notes, the guitarist writes that he wanted to explore the question of “what happens when a voice develops new tonalities as experience and maturity give it additional resonance?” and found that “what started out as an experiment quickly developed into a personal obsession.”

The new arrangements are sonically transformed but not structurally radical; the melodies remain pretty much intact, and the songs are all quickly identifiable. “Get Out of Your Own Way” adds a charmingly knockabout groove, while “Two Hearts Beat As One” (one of four songs featuring Edge as lead singer) gets lightly disco-fied. The more ambitious treatments sometimes feel like they’re trying to do too much: “The Fly,” with a bridge taking an almost Indian tinge, loses the frantic humor of the original, and “Vertigo” swaps the gleeful attack of its guitar riff for a jabbing cello part.

Mostly, though, Songs of Surrender takes things slower and more introspective, reducing the scope, tightening the focus. The songs’ familiar dynamics are often recreated in miniature; “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” originally centered on Larry Mullen, Jr.’s martial drumbeat, has no percussion at all, allowing the tragic events described in the lyrics to ring more clearly. “Beautiful Day” replaces soaring aspiration with a knowing murmur—it’s also one of several songs with revised lyrics; “Walk On” is updated for the Ukrainian struggle.

If the changes in Bono’s voice were a driving force in this project, the results are truly stunning. His vocals have been known to feel like one element in their swirling mix, but here there’s nowhere to hide, and the range and ease of his delivery is impressive throughout, slipping up into his higher register on a gorgeous “Stuck in a Moment You Can’t Get Out Or” or ducking and diving through “Electrical Storm.”

The Edge has said that Songs of Surrender was made with the awareness that most people listen through earbuds now, which is a telling explanation of the trade-off being made on Songs of Surrender. The communal experience offered by U2’s greatest anthems is replaced with something more personal, more individual. The momentum and release and exhilaration they define at their best becomes instead something that’s alternately lovely and flat, revelatory and redundant. Towards the end of the new version of “City of Blinding Lights,” an electric guitar figure chimes out and suddenly, briefly comes the rush of hearing a U2 song.

Are any of these recordings “better” than the originals? That’s really for each listener to decide—there’s too much history, too many emotions tied up in our relationships to these songs. It’s obvious to say that the earliest and latest material benefits more than the big hits, since most of us are less invested in them, and because the underwhelming response to U2’s last few albums means there are still gems to uncover (“Cedarwood Road” is certainly a keeper, though “The Miracle (of Joey Ramone)” is an improved arrangement of a still-uninteresting song). Also, forty songs is an awful lot to swim through, as Adam Clayton indicated in a recent interview, saying “something that may have been maybe better conceived as 15 or 20 songs started to mushroom into these 40 tunes.” (There is a 16-track version on vinyl, and a 20-track CD.)

It's unprecedented—a miracle, even—that the line-up of U2 has stayed intact into its fifth decade, that it really is the same four guys who met in high school still making music together. The final words on Songs of Surrender, the lyrics from “40” that have closed countless U2 concerts, are “How long to sing this song?” Even if this project is just a way for the band to reappraise its work and recharge its creative batteries, let’s hope that it keeps these songs going, longer and longer.

You Might Also Like