Spike Gjerde Champions Local Food Economies: 8 Mid-Atlantic Makers to Know

Justin T. Gellerson

It was an eclectic crowd, to say the least. There were, as you might expect at a candlelit dinner at the hip Line hotel in Washington, D.C., a preponderance of bearded millennials. But there were also middle-aged couples; a young Mennonite woman dressed in a long, pale blue cotton dress and a white bonnet; and a certified hipster with a swoop of jet-black hair decked in a lavender suit.

What connected them all was one lanky blond chef, Spike Gjerde, purchaser of apples, oysters, bacon, buckwheat, cider, cheeses, miso, sorghum, vinegar. On that frigid January evening, Gjerde (pronounced JER-dee) had invited this circle of mid-Atlantic makers to the opening of A Rake's Progress, his first restaurant outside of his hometown of Baltimore. Cocktails flowed; a bluegrass band, Chuck Darwin & the Knuckle-Draggers, played songs like "Old Home Place." Over a dinner of smoked pork loin with nectarine mostarda, buttered cabbage, and hominy, many met and swapped stories for the first time. "The night should have been all about Spike," remembers Rob Miller, owner of Maryland's Distillery Lane Ciderworks. "But for him, it was all about us, the growers."

It was classic Gjerde. Since he opened Woodberry Kitchen in a renovated Baltimore mill in 2007, the 56-year-old James Beard Award–winner has approached local sourcing with religious fervor. He forgoes olive oil and lemons, using locally grown and pressed oils and vinegars in their place. His team dries mint, lavender, peaches, and cherries—and even makes garlic powder. He refuses to buy from distributors, even when they buy from local growers, because he wants every penny to go to the farm. "Spike turns the whole paradigm upside down," says Ben Wenk, a seventh-generation farmer at Three Springs Fruit Farm. "It's not so much that his restaurants use what growers are producing; it's that he exists to provide more opportunities for those farmers."

Or, as Gjerde likes to say about his business, "Our motto is 'There's got to be a harder way.'"

There are, of course, other chefs who are champions of building local food economies. Sean Brock was instrumental in bringing back lost Southern ingredients such as Sea Island red peas and benne seeds, and Jeremiah Langhorne, a Brock acolyte, has made the sugar toad, a puffer fish from the Chesapeake, a must-eat at his Washington, D.C., restaurant The Dabney. But with a five-restaurant mini-empire, Gjerde's numbers are especially impressive: He spent $2.6 million with mid-Atlantic growers in 2017 alone.

And for Gjerde, it's not only about writing checks. He seeks out new producers and determines what they need to thrive. In 2013, when Nancy Bruns contacted Gjerde to tell him about her West Virginia salt company, he drove eight hours to tour the plant the next day. After deciding to stock Distillery Lane's cider, Gjerde introduced Miller to other Baltimore chefs to help him win new accounts. "If you don't have people like that, you aren't going to survive," Miller says. "And there aren't a whole lot of Spikes out there."

The reason, says Gjerde, is that as much as he doesn't want to admit it, local food is just more expensive. "A lot of people say, 'Wow, this is harder than I thought.' Then they just call Sysco [a giant distributor with $58.7 billion in sales in 2018]. But it's why we're doing it," he says. "Our job is to get more value back to growers. To get the farmers and oystermen and vinegar-makers paid so they can keep doing what they're doing. Otherwise we are just going to have corn and soy as far as the eye can see."

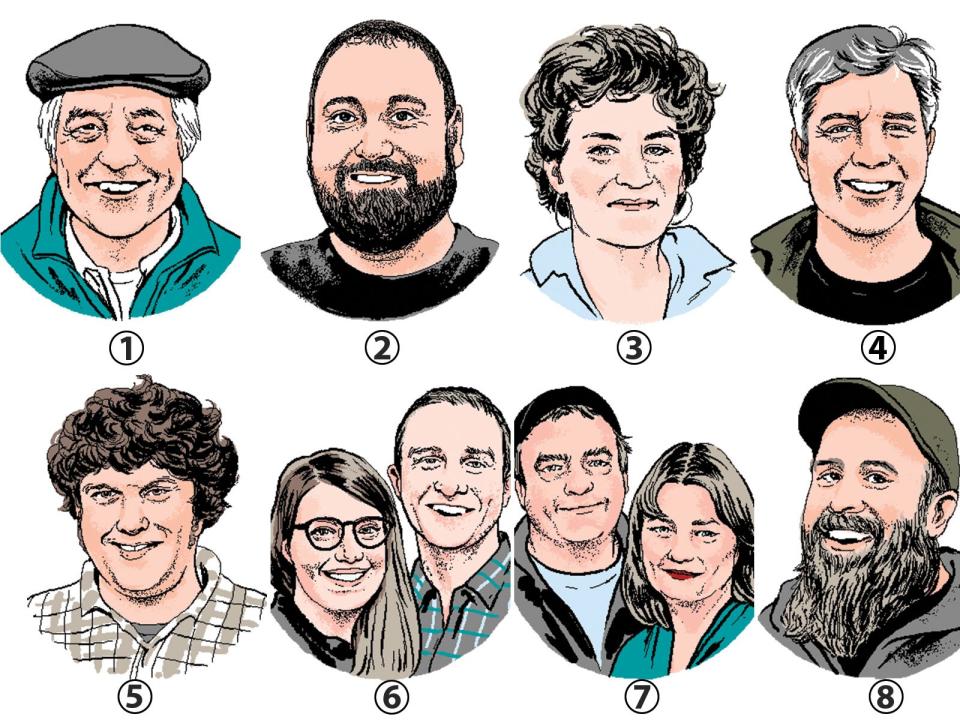

Meet Spike's Makers

Agata Nowicka

1. Rob Miller—Distillery Lane Ciderworks

Each year Spike Gjerde's favorite Christmas present is Rob Miller's box of a baker's dozen of apples. Inside might be a Roxbury Russet, a famous variety grown by George Washington, or a Caville Blanc, a French apple perfect for pies. They are the highlights of the 45 varieties Miller and his wife grow on their 95-acre Maryland farm, 20 of which they use to make dry, hard ciders that were once Marylander's go-to drink. A former financial guy, Miller planted his first apples in 2001. Gjerde was the ciderworks' first client and remains its most important—buying sweet, fresh cider, hard ciders, and apples for cooking and baking. For many small makers, a consistent customer is the best customer.

"The highlight of the year is when Woodberry's pastry chefs come out. They bring the crusts and we select 5 or 6 apples from the orchard. Then we drink cider and see which of the apples makes the best tarte tatin. Tough job."—Rob Miller

2. Chris Krantz—H.T. Krantz Honey Co.

Chris Krantz makes a lot of honey, some 12,000 pounds a year. But he doesn't think of himself as a honey-maker: He's a bee scientist, intent on breeding mite-resistant queen bees. But honey supports his scientific work, which is why Krantz is lucky to have found Gjerde, who takes about 85 percent of his crop of wild raspberry, black locust, and tulip poplar honeys.

3. Nancy Bruns —J.Q. Dickinson

Though it will come to a surprise to many, West Virginia was once home to some of America's largest salt mines. Thanks to Nancy Bruns, one of them, J.Q. Dickinson is back, but run with a very different philosophy. Instead of heating coal fires to dry the salt, Bruns places the salty brine in trays in a sunhouse where the water evaporates naturally creating chunky clean-tasting crystals. Instead of the low-paid jobs of yore, she's hiring ambitious, young West Virginians and spreading the wealth by buying jars, lids, labels, and tools from Appalachian producers. Her ancestors once produced thousands of pounds of salt a day. This year, Bruns will make 16,000. But it's a start, thanks in large part to her biggest client: Spike Gjerde.

"Looking back, there was no way I could not start making salt again. We had the family history, the land, and the desire for locally made products. The stars aligned."—Nancy Burns

4. Matt McShane—Great Wicomico Oyster Co.

It's no lie to say that Matt McShane's oyster company was cooked up right inside Woodberry Kitchen. He was sitting at the bar, slurping oysters on the half shell, and he said to the chef: You know, the ones I grow down in Virginia are better. He brought some in for Gjerde to taste, and it wasn't long before it was McShane's oysters on the menu. McShane sees Gjerde as a partner; he helped him to understand restaurant economics and what other food ventures had legs. McShane now sells biodegradeable soap to Gjerde too, made from a byproduct of the biodiesel he uses to farm oysters. Last year, at Gjerde's urging, he started raising rabbits, a high-protein meat, that Woodberry serves up chicken-fried with fish peppers and honey.

"I told Spike the oysters I grow down on my dock in Virginia are better. So I brought some in, and he tasted them and said, 'You're right. How do we do this?' And I said, I have no idea."—Matt McShane

5. Ben Wenk—Three Springs Fruit Farm

Six generations of Ben Wenk's family had grown fruit in Adams County, Pennsylvania, before he joined the family business. With a degree in agroecology, he expected to help improve the land, using fewer pesticides and modern orchard management. And he has. But Wenk's biggest accomplishment has been transforming how the farm does business—and with whom. As recently as a decade ago, the farm sold to almost exclusively to wholesalers. "We had never met the people who actually ate our food," Wenk says. Today, more than half of the 450-acre farm's sales of apples, peaches, apricots, berries, eggplant, okra, and more are sold directly to consumers at farmers markets and to restaurants like Woodberry Kitchen.

"I always joke that when you choose agriculture as a career, you've given up on being wealthy or ever retiring. But I have this overwhelming desire to make sure Adams County remains a lush green beautiful place."—Ben Wenk

6. Isaiah Billington & Sarah Conezio—Keepwell Vinegar

After serving as pastry chefs at Woodberry Kitchen, Isaiah Billington and Sarah Conezio went off in search of a business of their own that was both environmentally sustainable and supportive of small farms. Their answer? Vinegar. They use anything farmers have an excess of, from berries and tomatoes to ramps and celery. Gjerde was their first customer and remains an anchor for their business.

7. Colleen & Michael Histon—Shepherds Manor Creamery

The Histons opened Maryland's first sheep's milk creamery as their second career. It was a leap; though they had raised sheep with their kids for 4-H, they didn't know the business of cheese. But they had a knack—and have introduced Tomae, a gorgeous washed-rind wheel; a mild baby feta; and, of course, the sheep's milk ricotta that Gjerde serves on flatbreads with honey and seasonal fruit.

8. Josh Leidhecker—Susquehanna Mills

Josh Leidhecker is not a romantic foodie—someone who tasted organic oils in France and was moved to make them. He's an inveterate tinkerer, a problem solver. In 2004, he was in the construction business and wanted a cheaper fuel. He turned to biodiesel. And when a friend asked him if the oil was good enough to fry a chicken, he decided to find out. "It was delicious," he remembered. "And that's when I decided, I'm going to make this stuff." Today, Leidhecker farms 150 acres and buys from a network of regional farmers to make organic never-chemically treated cooking oils. "He's a mad scientist when it comes to mechanical processes, but he also cares a lot about farming," says Gjerde. "I'm so happy that he's in our orb. Or that we're in his."

"Why did I start making oil? Curiosity … There are things I do that there really isn't ever a reason for?"—Josh Leidhecker