Steve Jones's Sex Pistols life is stranger and filthier than fiction – can Danny Boyle do it justice?

Anarchy, filth and fury will likely be exploding into living rooms around the world after it was announced this afternoon that Trainspotting filmmaker Danny Boyle will direct a six-part TV biopic about punk rockers the Sex Pistols.

Pistol will be based on guitarist Steve Jones’s no-holds-barred 2016 autobiography Lonely Boy: Tales from a Sex Pistol. Production will start in March with a cast including Game of Thrones actress Maisie Williams.

The film will focus on Jones’s early years and how the punk subculture caused both moral outrage and a fashion revolution in the buttoned-up London of the mid-1970s. “Imagine breaking into the world of The Crown and Downton Abbey with your mates and screaming your songs and your fury at all they represent,” Boyle said. “This is the moment that British society and culture changed forever. It is the detonation point for British high-street culture.”

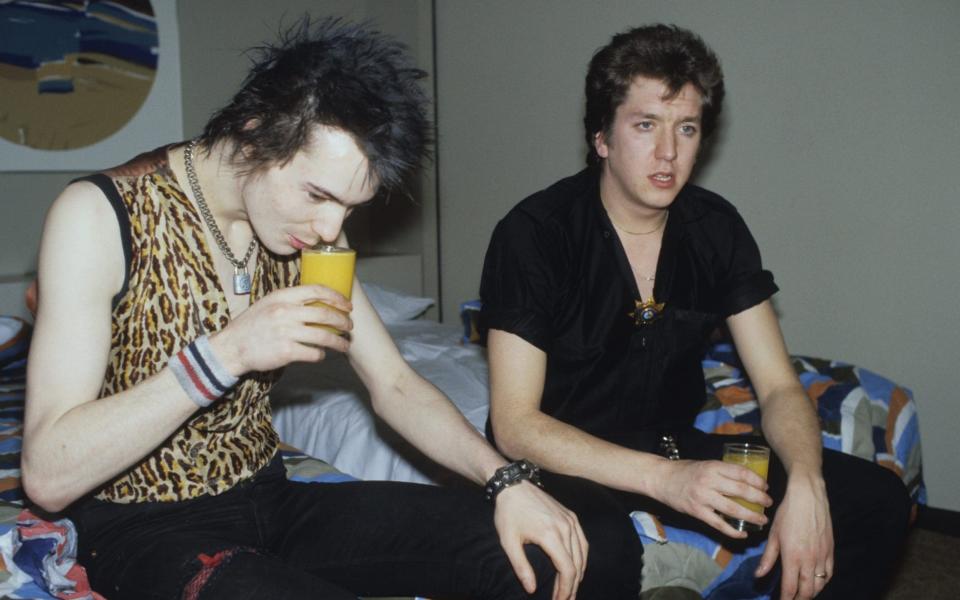

Pistol will star a host of young up-and-coming actors in the lead roles. Toby Wallace, who starred in last year’s coming-of-age film Babyteeth, will play Jones, 1917’s Anson Boon will portray singer John Lydon, while doomed bassist Sid Vicious will be played by Enola Holmes actor Louis Partridge. Fabien Frankel, who can currently be seen as naive French traveller Dominique Renelleau in BBC’s The Serpent, will play original bassist Glen Matlock, while Williams will play punk icon and early Pistols associate Jordan.

It is unknown who’ll star as Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood, the boutique owners who helped steer the band to success. Pistol will be made by FX Productions, the company behind A Teacher. No release date has been given and it is unclear which channel or platform the show will run on, although FX has an ongoing relationship with the BBC.

In releasing a biopic series, the seminal punk band are following a well-trodden path. After the box office success of Queen and Elton John biopics, we’ll soon see films about Aretha Franklin, Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan and Madonna. The Pistols already have form when it comes to being immortalised on screen. Pistol comes four decades after the band released their own film, the iffy The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, and 35 years after Gary Oldman starred as Vicious in Alex Cox’s Sid and Nancy. The band’s story was also recounted in documentary form two decades ago in Julien Temple’s acclaimed The Filth and the Fury.

But if Lonely Boy’s source material is anything to go by, the new film will be far from the sanitised portrayal of life in a band that music fans saw in Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody. Jones’s book is a gritty and gob-flecked tome that deals with issues of sexual abuse, substance abuse, sex addiction and kleptomania. As Jones memorably puts it in his book, he’d have sex with anything that moved and steal anything that didn’t (including nicking David Bowie’s equipment from Hammersmith Odeon at the Ziggy Stardust farewell shows). The heart of Jones’s book – where it is at its most vivid and, at places, disturbing – lies in his account of growing up in post-war London. And this is where Pistol is likely to diverge from standard rock biopics. It will be the band’s origin story – punk’s own Batman Begins.

Boyle said that Jones’s backstory is key to the Pistols’ narrative. “At its centre was a young charming illiterate kleptomaniac – a hero for the times – Steve Jones, who became in his own words the 94thgreatest guitarist of all time. This is how he got there,” the Oscar-winning director said.

Boyle excels at portraying cities’ gritty underbellies. Just look at the Edinburgh of Trainspotting or the post-apocalyptic London of 28 Days Later. The London that Jones describes in Lonely Boy is a cold and joyless place, strewn with debris, building sites and corrugated iron fences that shred the skin of people trying to scale them. As a youth Jones ran wild in Hammersmith and Battersea, tearing around in stolen mopeds and nicking wallets from the changing rooms of private school St Pauls. He’d skip school, break into the hulking Battersea Power Station to climb its chimneys, and was arrested 13 times. London was grey and dull. It took punk to jolt it from its languid stupor.

Jones’s early years were also personally dark. He writes about being “fiddled with” by his stepfather aged 10 in a Shepherd's Bush flat while his mother was in hospital having a miscarriage. The incident, as Jones discovered in therapy decades later, led to his addictions to sex (both having it and becoming a “peeping Tom” watching other people have it) and his kleptomania. The abuse also led him to seek escape in music. Indeed, it was music, Jones says, that saved him from “getting swept away by a tide of f_____-up s___”.

The passing of time has diluted punk’s primal howl. Its snotty, violent rage is a distant memory. The scene’s once-shocking DIY aesthetic of safety pins, ripped clothes and spiky hair became a clichéd fancy dress staple years ago, while Jamie Reid’s cover art for the Pistols’ God Save The Queen – featuring a defaced Queen Elizabeth II – can now be found on postcard racks in London tourist hotspots alongside snaps of Beefeaters and Big Ben. So it’s easy to forget the very real societal panic caused when Lydon (stage name Johnny Rotten), Jones, drummer Paul Cook and Matlock (who was replaced on bass by Vicious in 1977) burst onto the scene.

As the NME journalist Neil Spencer said in the magazine’s first review of the band in February 1976, they were “a quartet of spiky teenage misfits from the wrong end of various London roads” (although Jones would claim he was the true outsider: the others came from comfortable homes). As Jones memorably told Spencer that night, “Actually we’re not into music. We’re into chaos.”

This much is true. Chaos reigned. But what Lonely Boy describes brilliantly – and something that Pistol writers Craig Pearce and Frank Cottrell-Boyce, who wrote the script for Boyle’s opening ceremony at the 2012 Olympics, will hopefully capture in their treatment – is how the story of punk was also more nuanced than all this. For example, Jones was a massive Rod Stewart and Roxy Music fan. And before becoming a punk he dipped his toes in different youth scenes: he loved Motown, dabbled with the Teddy Boy crowd and for a while was even into progressive rock, the antithesis of punk.

As the punk scene exploded, Jones started resenting its anti-success ethos: coming from nothing, he wanted to enjoy the trappings of what he’d achieved. Meanwhile the Pistols’ most infamous episode, when they swore live on TV during a December 1976 interview with Bill Grundy, is often seen as punk’s crowning glory. But Jones hated it. He describes it as the beginning of the end for the band. Before Grundy, it was all about the music. After Grundy, it was all about the media. Tours were cancelled and the band entered a tailspin. You can sense the regret and sense of ‘What if..?’ in Lonely Boy.

Pistol’s portrayal of McLaren and Westwood will be fascinating. As the band’s manager, McLaren is often characterised as a sly svengali, out for what he could get. But Jones sees it differently. As a working class lad, he loved hanging out in McLaren and Westwood King’s Road boutique Let It Rock (which eventually changed its name to Sex). The pair opened his eyes to a different world – a London full of “avant-garde art-world” people, toffs and health food. “Malcolm and Vivienne were like a bright light in the darkness I’d come from,” Jones writes. He even lived with them in Clapham for a while when he was homeless. Trainspotting’s Kevin McKidd and Jonny Lee Miller (Tommy and Sick Boy respectively) both look uncannily like McLaren, so Boyle could have some fun with the casting there.

Lonely Boy is stuffed with memorable characters. There is Virgin Records’ Richard Branson (“catweazle”), who signed the Pistols after both EMI and A&M dropped them. Jones’s early girlfriend Chrissie Hynde features strongly, and there are stories involving everyone from Midge Ure (who McLaren wanted to be the band’s singer at one point) and Lemmy from Mot?rhead, from whom Jones bought speed. There is also a story about an X-rated party trick by actor John Bindon, who reportedly had a relationship with Princess Margaret.

Jones describes in great detail swiping gear from Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust farewell shows in the summer of 1973. He claims the reason the sound was so bad in the concert film of Ziggy’s last show was because he’d swiped the microphones the night before. Ziggy wasn’t the only one who (nearly) didn’t play guitar. Jones nicked a coat from Ronnie Wood, a gold disc from Bryan Ferry, and 10cc’s guitars, among a vast haul of other stuff including most of the Pistols’ early on-stage equipment. As a youngster, a picture of Jones appeared in The Sun after he was persuaded to demonstrate a toy in Selfridges. The reason he looked so uncomfortable was because he’d been there shoplifting and had stolen toys hidden under his clothes.

There was, of course, no happy ending to the Pistols story. The band lasted for just over two years and released just one proper studio album. A year after their break-up, Vicious died of a heroin overdose in New York. “The Sex Pistols were born to crash and burn, and that’s exactly what we did,” Jones writes in his book. Despite the temptation, Boyle needs to make sure we don’t like the characters too much. The band could be nasty and puerile. In June 1976, Vicious attacked a journalist with a rusty bike chain in Oxford Street’s 100 Club. And he once almost slit the throat of an innocent photographer on a tour bus because he coveted his biker boots.

Pistol promises to be great if it steers away from sugar-coating and pastiche. It needs to convey Jones’s snottily subversive wit but also tell the band’s story in all its grotty, dark glory. It should, at least at times, shock and disturb as much as its subjects’ music did over 40 years ago.

Lydon once said that the Pistols were “against bureaucracy, hypocrisy and anything ending in ‘y’”. Let’s hope this includes hagiography too.