Stewart Copeland: ‘I’m a capitalist – get over it!’

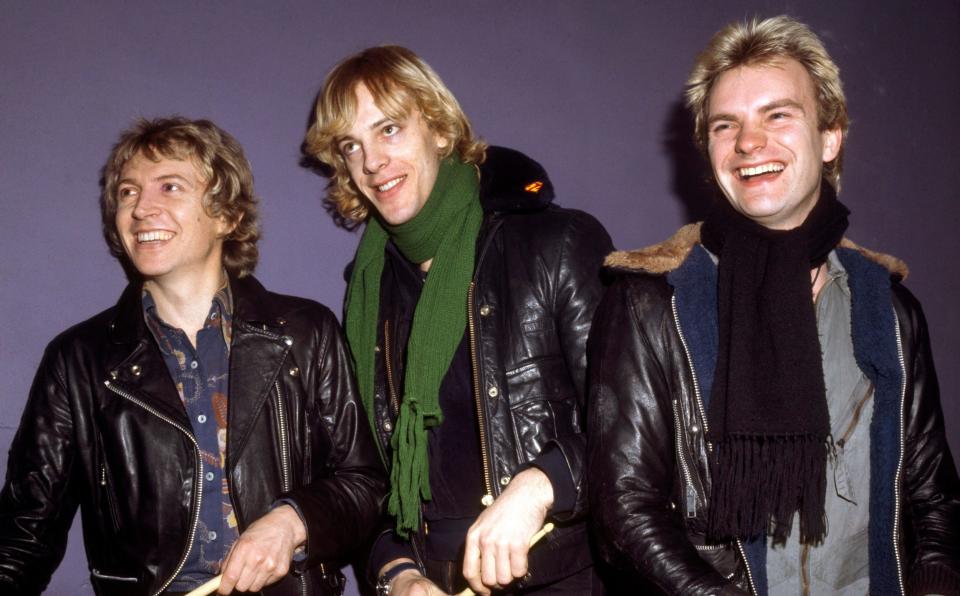

In June 1978, Stewart Copeland, Andy Summers and Gordon “Sting” Sumner appeared on Top of the Pops for the first time. Introduced as “Klark Kent” by presenter Tony Blackburn, the group proceeded to mime their way through the song Don’t Care, a track written and performed solely by Copeland that had been deemed unsuitable for the trio’s full-time, fledgling band The Police. So as not to waste charisma on a part-time project, that Thursday night the musicians covered their faces with masks, sunglasses and heavy makeup.

“The first time any of us had a hit was Klark Kent,” Stewart Copeland says. “It was the first one out of the gate, the first time the three blonde heads were on TV, on Top of the Pops. To see Sting go there was my favourite brag, which I never fail to remind him of, to my great hilarity. I’m sure he loves being reminded that his first time on national television was wearing a gorilla mask, miming a bass line.”

Don’t Care wasn’t quite a hit, but in reaching number 48 in the charts, the song’s modest success persuaded A&M Records to allow The Police to record their debut album. Released five months later, Outlandos d’Amour would go on to sell more than two million copies.

“But,” Copeland says, “[Sting] did get his revenge by writing 20 hits for The Police. The next time I was on national TV, I was in his band.”

This week sees the release of a deluxe edition of the eponymous Klark Kent album, the authorship of which Stewart Copeland refers to in the third person, as if it were the work of a stranger rather than something he himself wrote and performed in its entirety. “I’d wake up in the morning… and discover there were these tracks on the tape machine that he’d left behind,” he says. “I’d had a visitation from Klark Kent.” Evidently, the uninvited guest had a taste for new-wave vignettes in the style of Devo.

Now aged 71, he remains irrepressible. Watching him across Zoom in the Los Angeles home he shares with his second wife – with whom Copeland fathered three of his seven children, including one adoptee – one is reminded not of a rock star but of an immaculately preserved pensioner raised on a diet of methamphetamines and Sunny Delight.

Rarely do I reach the end of a question before a response of some kind bursts forth, less an answer, perhaps, than a gateway into a web of tangential topics. Fluid and intelligent, the rhythms of his speech echo a playing style that is as recognisable as it is widely known. But as the drummer with The Police, that most disputatious of bands, it’s not hard to imagine the nature of the long-standing clash of personalities between him and his contemplative frontman, which got so bad the pair even came to physical blows, with Copeland reportedly once accidentally breaking one of Sting’s ribs for stealing his copy of the New York Times.

On the group’s reunion tour of 2007 and 2008, a stadium-packing campaign that saw each of the three music-makers trouser a million dollars a night, tensions between Stewart Copeland and Sting were mitigated with the help of a therapist. “I’d heard that the Rolling Stones had had therapy,” he says, “so I wanted some of that band therapy. So we got some and they tweaked out of each of us our point of view, about which we were both gobsmacked. We could not believe what we were hearing from the other party. And it changed everything.”

The pair discovered that their problem was a clash of musical philosophies. “I want to burn down the house… I want to bang sh-t,” Copeland explains. Sting, on the other hand, “has a higher motivation. He runs quiet and deep, whereas I’m noisy and shallow. For him, music is a beautiful escape from the hurly-burly world, a place where he can explore ideas from some of the dense literature he reads and some of the deep thoughts he has that are native to himself. He’s a poet, mainly. And for a poet, those words [he writes] are very important, while the music is in the service of the poetry.”

Stewart Copeland arrived in England in the sixties from his childhood home in Beirut. His Scottish mother had worked for the British intelligence services, while his father worked for the CIA – an agency he helped to create – as an operative in the Middle East tasked with ensuring the smooth passage of oil to the United States.

But while tacking to the Right, Miles Axe Copeland maintained a sense of fairness that at times expressed itself in surprising ways. In his book The Enemy Within: The Secret War Against the Miners, author Seumas Milne revealed details of a phone call from Copeland to Arthur Scargill warning the National Union of Miners president that the secret services were conspiring against him in unethical ways. “I cannot verify [that] but it sounds very much in character,” says his youngest son today.

One imagines that Stewart Copeland’s own political leanings raised the eyebrows of at least one of his bandmates. In 1985, three months after the end of Miners’ Strike, Sting released the pro-coal song We Mine the Black Seam (from his debut solo album The Dream of the Blue Turtles) on which he sang of men whose “blood has stained the coal [and who] tunnelled deep inside this nation’s soul”. The following January, Copeland took part in a roundtable interview for the Melody Maker in which he argued against the Red Wedge movement (the 1985 movement aimed at shepherding young people towards the Labour Party).

He said at the time: “The thing about socialism is that it’s great for writing songs about – you have intense emotive issues [...]. Capitalism just doesn’t sound romantic. I believe that money is love – but it doesn’t make a great lyric. I believe that money is the root of all civilisation, and ideology is the root of evil – but you can’t sing that in a song. It sounds horrible!”

Reflecting on his politics now, Copeland says: “Me and my mate Sting are violently opposed to each other politically,” he said. “Not an inch of shared ground.”

Even by his standards, Stewart Copeland seizes my question as to whether he remains on the Right with uncommon vigour. “Yes!” he says, evidently delighted. “I’m a capitalist, get over it! And, anyway, compared to England, any American Left or Right is way to the Right of every Brit. And in London, I was considered to be all Right-wing and stuff. But not really. I vote Democrat. Right now, I don’t care which party is [in office] so long as Trump doesn’t get in. It’s beyond the philosophical difference between Left and Right.”

Apparently determined not to be typecast, Copeland then goes on to praise Ken Livingstone for being “a great guy” who did “a great job for London”. Even further to the Left, he somehow managed to find common ground with director Ken Loach, for whom he scored the films Hidden Agenda, Riff-Raff and the brilliant Raining Stones. “I actually asked him, ‘Do you mind working with an arch-capitalist?” he recalls. “And he said, ‘No, you’ve got it right. You’re an upside-down pyramid.’ I do all the work. I create the wealth and I use that wealth to hire people. I’m not just creating the wealth and taking the money… So he forgave me.”

Stewart Copeland has also scored films for such directors as Francis Ford Coppola, Oliver Stone and George Miller. But despite a career that encompasses classical music, opera and literature, it was his work this year on the lavish Police Deranged for Orchestra album that served as the catalyst for a genuine epiphany. While arranging 11 of the trio’s tracks for band, orchestra and singers, the drummer who “only ever saw the back of [Sting’s] head” without sparing a thought for “what he was singing about” was at last able to view the bigger picture.

“Doing those arrangements… [meant] that I found out what those songs mean,” he says. “I found out what Sting was doing with those songs. And I did come to an uncomfortable realisation. Now don’t tell him I said this, but the man is a genius. He really is, and I just have to deal with that.”

Klark Kent – The Complete Studio Recordings, by Klark Kent, is available now