A strange cult invades an American ski resort – and then does nothing

In Ashani Lewis’s Winter Animals, a new world is being built in the Oregon mountains. This world is populated by four British Oxford graduates inspired by Charles Fourier, the eccentric 19th-century proto-socialist. They refer to Atomic Habits, James Clear’s 2018 self-help book, and discuss theories of tragedy.

We’re introduced to this group, in their mid-twenties, via Elen, a 38-year-old who has lived in Oregon for most of her adult life, whose husband has just left her, and who abandons her life as a quail-egg packer to squat with her new comrades in an empty ski resort. The action is limited to skiing and drinking: the group imagine themselves to be bound by some mutual, possibly sexual, understanding, but are committed more to the slopes than each other.

All in all, it’s a strange premise. Winter Animals, as is the vogue, is a novel concerned with class: the four Britons are explicitly written as wealthy, and through Elen, we witness them as irritatingly carefree. At times, there could have been more interrogation of that dynamic: everyone, including Elen, the “normal” one, can ski. Still, she’s our mole on the inside, in the sense that she is never quite of the group – she remains an honorary member. Moments of precarity, in which the cult imagines itself to be discovered, are well-crafted: a car appears in the driveway; a sentence is misinterpreted. (Still, at times these are overplayed, as when, in a sort-of vision, Elen sees a tap run with blood, and pictures the heads of her friends exploding.)

Lewis is at her best when she employs a sentence-level stutter. The sun “demanded migraines at her”, I read, and then read again – it’s “diamonded”. Things are green “like Monet or dollars or like silver or the word frieze”. A better way, I think, to show the feeling’s uncanniness: it’s much less explicit than, say, the later acid-trip that has forests turning into Greek letters.

Despite its overtly philosophical concerns, Winter Animals is also peppered with internet-inflected phrases. Elen thinks they’re “doing a crime”: a grammatical structure all too familiar to those who spend an extended amount of time online. At one point, there’s a conversation about the Dyatlov Pass incident, which, while a fascinating part of Soviet history, is most obviously a favourite of social-media sleuths. These moments reveal more about the writer than the characters: among the talk of Fourier, Lewis suddenly feels present.

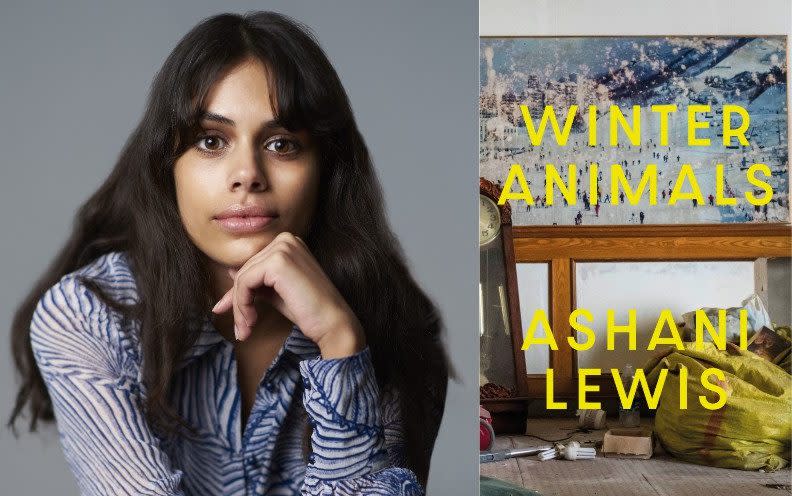

With its talk of anagnorisis and eroticism and Tudor princes, it’s clear that Lewis is indebted to Donna Tartt’s The Secret History; this version has YouTube videos and Miley Cyrus songs as well. But it’s fair to offer modernisation, and the novel’s problem isn’t context, but style. While the ambition is clear, the expression lacks subtlety: you wish that Lewis trusted her reader to find meaning without exposition. Nonetheless, Winter Animals is a debut full of ideas. I have the sense that this is the first of many new worlds.

Winter Animals is published by Dialogue at £18.99. To order your copy for £16.99, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books