Tim Booth on cults, Coldplay and why Sit Down is ‘a medicine we need right now’

There is a song on the new James album that is unbearably sad. Recover is a track about singer Tim Booth’s father-in-law dying in the first wave of Covid-19. One verse documents his rapid deterioration: in a few lines 84 year-old Saville goes from having a sore throat to being on a ventilator. Despite the peppering of hope throughout the song, he never recovers. It’s a harrowing listen.

As British expats living in California, Booth and his wife Kate were unable to be with Saville when he died in Watford General Hospital in spring 2020. However they were able to FaceTime him as the end neared, with his wife – Kate’s mother – also on the call. Speaking about it today, Booth is clearly still moved by the memory. Saville – a fit man and an avid swimmer – was lucid and unafraid, he says, and they were able to have a “beautiful farewell”. At his father-in-law’s request Booth sang Sit Down, the anthem that made James household names back in the ‘Madchester’ era of the early Nineties.

Many of us know the song so well that we no longer notice its lyrics. Those less inclined to admire James’s work may still link the song to easily-mocked visions of waggish students in ill-fitting jumpers sitting down on the dancefloor at indie discos. But reframed in such bleakly poignant circumstances, Sit Down takes on fresh meaning. “I sing myself to sleep / A song from the darkest hour,” it starts. Great songs do that: they adapt to circumstances. Booth describes the scene in hospital as a “really powerful moment”. The call ended. Saville drank a Bellini – his last request – and died within 45 minutes.

“He came off the machine. They gave him a Bellini. All those amazing volunteers who helped run the NHS went out and got him a peach juice. And then he passed really quickly,” says Booth with a soft, slightly posh mid-Atlantic-via-Manchester inflection. When Recover was released as a single in May, the band dedicated it to the families of those lost to the pandemic.

It is a standout track on All The Colours Of You, James’s 16th studio album; despite everything it's a life-affirming affair. The album continues James’s late-career creative roll. Their last two albums reached the top ten (only Adele’s mega-selling 25 stopped them from topping the charts in 2016), and an arena tour later this year has sold faster than any previous James tour. Part of the allure is their towering tunes: songs like Laid, She’s a Star and Come Home are festival-ready belters.

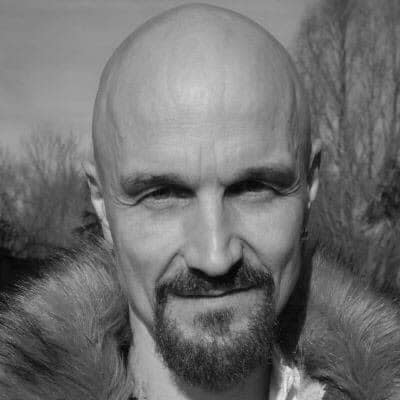

Much of the appeal is down to Booth himself, a sort of Bono for the rave generation. The bald, yoga-loving 61 year-old’s face lights up when he describes the “healers, shamans and lunatics” he was surrounded by in Topanga Canyon (his family left when wildfires drove them out). Anyone who has seen Booth dance on stage is unlikely to forget it – imagine a spider doing an impression of a Catherine Wheel. In the days of "normcore" pop stars like Ed Sheeran and Lewis Capaldi, the eccentric Booth is a refreshing counterpoint.

All The Colours Of You almost never happened. With James’s eight members scattered by geography during the pandemic, recording together became impossible. The album’s demos, which were based on 17 days of improvised jams recorded pre-Covid, looked set to gather dust. But it transpired that Grammy-winning Irish producer Jacknife Lee lived two miles from Booth in Topanga. The U2, Taylor Swift and Killers collaborator was free. So after a bonding session with Booth (“he could keep you entertained for days,” Lee tells me), he agreed to produce it.

A renowned remixer, Lee chopped up James’s demos and reassembled them with electronic textures, modified structures and surprising loops. He and Booth worked together in California while band members sent in parts and collaborated from afar. Jangly guitar rock is gone. In its place are smatterings of Can-esque motorik Krautrock, wonky synths and banging techno.

“The band didn’t recognise some of the bits because they were just totally mangled,” Lee says of the process. “I guess I was disrupting. The great thing was they were totally open to it.” Booth says the producer “jammed with our jams”. Bass player Jim Glennie describes the record as “more extreme” than usual and – simply – “massive”.

Over nearly four decades James have genre-hopped from playing indie-rave music to thousands in Manchester’s G-Mex centre to traversing the US with Neil Young on an acoustic tour (“Magical. He was like us. A bit shambolic,” says Booth). Their appeal is broad. A wonderful anecdote from when Booth did some acting demonstrates this.

In 2005 the singer played villain Victor Zsasz in Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, starring Christian Bale. The story appeared in the NME a few years ago and has been repeated elsewhere. But I ask Booth to retell it for Telegraph readers.

“I had to be made up for about two and a half hours with scars all over my chest and face every day,” Booth explains. “I hadn’t seen Batman at all, and on the about the fourth day Batman is three chairs down in the make-up trailer. He’s in full regalia and he finished before me.” The singer could only watch in his mirror as the Caped Crusader stood up and walked behind him. “And he says [adopts the Christian Bale Batman voice] ‘Are you Tim Booth?’ And I go ‘Yeah.’ ‘From the band James?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘Laid saved my life. One of my favourite albums.’ And then he walks off. I’m sitting there going ‘Batman likes our music!’”

From superheroes to students and everything in between, James fans run the gamut. The band’s long association with producer Brian Eno (who worked on five albums) has also made them musical touchstones for other artists. Coldplay’s Chris Martin once told Booth he became a singer because of him. Martin is also said to have asked Eno to work on Coldplay’s mega-selling Viva La Vida and Mylo Xyloto albums due to his work with the band.

Booth acknowledges this “cross-pollination”. Indeed, some of the new James record sounds like Coldplay. The masters doff their caps to the students. Influence is, as Booth suggests, a two-way street. He also says that Eno’s game of Oblique Strategies, the producer’s card-based method of encouraging creativity in the studio, fitted James’s penchant for developing songs through freeform jams. “Honour Thy Error as a Hidden Intention,” Booth says, quoting one of Eno’s cards. “That is James in a nutshell.”

The band have always been contrarians. They refused to release Sit Down in America because, they argued, their sound was evolving. Does Booth regret this? “The part of me that is really worried about the bank manager is really pissed off,” he says, adding that it was a “very foolish move”. But James grew up at a time when indie was indie and the mainstream was sneered at. It took them seven years to taste success after they formed in 1982. This was partly because Booth and a bandmate were members of the cult called Lifewave (Booth describes himself as a “monk”).

“I was meditating two hours a day, 16 hours every weekend, celibate, no alcohol or drugs for three and half years,” Booth explains. In one particularly fallow year, James only managed to write one song. “Any other band would say that was a lean year but we had a blast,” he says. The singer maintains that this period was “crucial” for the band to develop. Today’s industry obsession with overnight success would never afford young musicians such luxury.

As we talk of cults, Booth links the conversation to the present day. It’s vintage him: eloquent state of the nation discourse spiced with a droplet of new age conspiracy theory. “Right now, we are living in the time of cults. Consensus reality is falling apart and we’re all in our own little echo chambers created by algorithms that keep showing us only what we want to hear. QAnon, Donald Trump – what an amazing cult he is,” Booth says.

He’s right, of course. We choose who we follow on social media, Spotify plays me what it thinks I like, and Sainsbury’s automatically sends me avocados in my weekly shop. I’d just never think to link these things to the crumbling of consensus reality. But that’s probably why I haven’t sold 25 million albums.

Booth says James’ll play songs of hope and unity in their string of upcoming live shows. In other words, they’ll play the hits. They’ve often omitted Sit Down but probably won’t this time. Aside from Booth’s personal experience last year, the song’s message about solidarity among outsiders (“Those who find they’re touched by madness / Sit down next to me”) seems to have chimed with a whole new audience. Booth recently heard the song referred to as “the bipolar national anthem”.

“I think coming out of lockdown that song has meant quite a lot to people. It’s definitely had a resurgence of relevance,” says Booth. Part singer, part soothsayer, he knows what to do. “It sounds like a piece of medicine that is needed right now.”

All The Colours Of You is released on June 4 on Virgin Music Label & Artist Services