A Treasure Hunter Found King Tut's Tomb—and Accidentally Cursed His Friends to Death

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

This story is a collaboration with Biography.com.

On February 16, 1923, Howard Carter, guided by the flickering light of oil lamps, ventured into the depths of a long-hidden subterranean burial site that he and his benefactor uncovered in Egypt’s storied Valley of the Kings. While exploring its innermost chamber, Carter discovered what many would consider the holy grail of an archaeologist’s quest: the undisturbed, sacred tomb of the ancient boy pharaoh known as King Tut.

Carter’s incredible find turned a youthful monarch who, according to Biography, “achieved little” during his brief reign, into the most famous pharaoh of modern times. But did Carter’s discovery also unleash a terrible affliction that claimed the lives of several men on his team?

Recent research, unmasking layers of myth, suggests that the notorious curse of King Tut might be anchored in realities far more scientific than supernatural, with a possible kernel of truth hidden amidst ancient dust and mysterious hieroglyphs.

To unravel the science and secrets of the ancient tomb, we must journey back to the source: the tale of King Tut’s curse and the sequence of improbable events surrounding the man who, unwittingly, may have set it in motion.

Setting the Scene

In a dimly lit space adorned with a sign that reads, “Field Expedition. Season 1921. British Museum,” three men toil away on the findings of the day. After assembling bits of pottery, and examining a sarcophagus, the archaeologists turn to a casket emblazoned with gold. They take notice of a remarkable component of the casket: an unbroken seal of a pharaoh.

Before the eager men can break it, one takes note that the casket also bears a curse: “Death, eternal punishment, for anyone who opens this casket, in the name of Amon-Ra, the King of the Gods.” But the leader of the expedition brushes aside such superstitions, and his hot-headed protege is eager to open the casket, unknowingly damning them all to a nightmarish fate.

This is the dramatic opening scene of 1932’s The Mummy, which followed Universal’s previous two monster movies from the year before: Dracula and Frankenstein. While those flicks came from the pages of Bram Stoker and Mary Shelley, Universal’s newest menacing monster was instead based on a true story.

Seeking a suitable vehicle for star Boris Karloff following Frankenstein’s success, Universal’s head of production, Carl Laemmle Jr., brought in writer John L. Balderston to pen a script about Italian cultist Alessandro Cagliostro. But Balderston shifted the focus to a topic of the occult, an area he knew much better, transforming a narrative about a charlatan from the 18th century into a “ripped-from-the-headlines” horror story—one that gave the story of a mummy’s curse an immortality all its own.

In fact, these “ripped-from-the-headlines” elements originated from Balderston himself. Ten years earlier, he had been the very journalist for the New York World who reported on Howard Carter’s historic unsealing of King Tut’s tomb.

Who Was Howard Carter?

Born into a modest family in Kensington, London in 1874, Howard Carter was a sickly child who found his purpose in the world of art. Under the tutelage of his father, Samuel, a successful artist, Carter was homeschooled, honing his skills with pencil and brush—a talent that would ultimately pave his way to the sands of Egypt and into the annals of archaeological legend.

Carter didn’t develop a desire to explore distant lands until he was a teenager, when his dad painted the portrait of William Tysen-Amherst, described by Biography as “a well-known Egyptologist.” The Tysen-Amherst estate housed an extensive collection of Egyptian artifacts, obtained (or perhaps plundered) during the British occupation of Egypt that was happening at that time.

Carter was instantly captivated by Tysen-Amherst’s private museum. He frequently spent time at the estate and became a self-taught Egyptologist, in hopes of someday discovering Egyptian relics of his own.

That opportunity soon came because of his artistic skills and lack of formal education. As Biography notes, at age 17, Carter headed to Egypt in 1891 to assist the Egypt Exploration Fund’s excavation of the Middle Kingdom tombs at Beni Hassan. Why the undereducated, inexperienced Carter? As author Daniel Meyerson suggests in In the Valley of the Kings, “[Carter’s] services could be obtained cheaply, which was just what the recently founded Egyptian Exploration Fund needed. They could not afford to hire another expensive gentleman-scholar.”

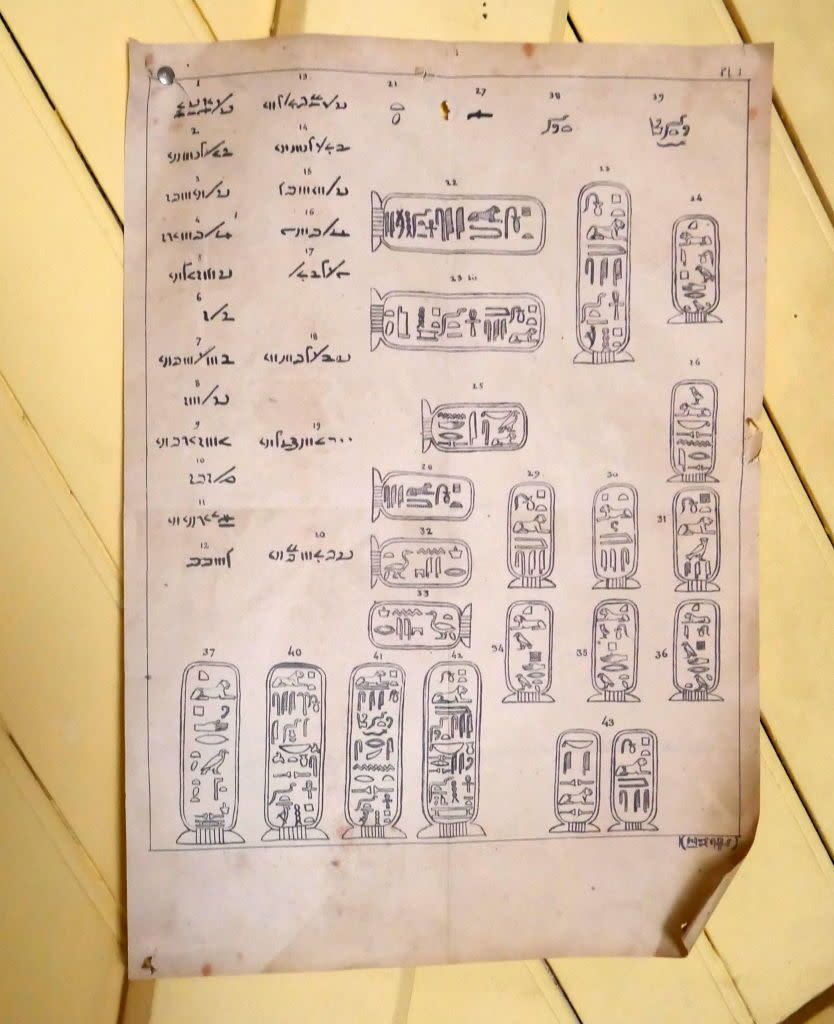

Carter joined archaeologists as they journeyed through sites such as Amarna, Deir el-Bahari, Thebes, Edfu, and Abu Simbel, creating detailed illustrations of their discoveries, since photographic technology at the time wasn’t sufficiently advanced for the task.

For years, Carter chronicled these sites, developing celebrated and innovative techniques for capturing wall reliefs. But would the aspiring archaeologist ever get an expedition of his own to lead?

Enter, in 1907, the wealthy English aristocrat Lord Carnarvon, who was fascinated by Egyptology and had the deep pockets to fund British excavations of Egypt, as Meyers describes:

“To dig with any success (“to excavate,” in the polite lingo), one needed knowledge. And one needed money- a great deal of it. Thus, they often came in pairs, the archaeologists and their sugar daddies. They were famous ‘couples’—inseparables for all their differences of temperament and background.”

For someone like Carter, a figure like Lord Carnarvon offered the essential financial backing and encouragement to ultimately take the helm of excavation projects. And for Carnarvon, as Meyerson writes, the potential rewards from these ventures were far greater than what he could pull in “at the racetracks and roulette tables of their usual watering holes.”

In 1914, Lord Carnarvon received a license to dig at a site “where it was believed the tomb of King Tutankhamun rested,” and hired Carter for the job. Tutankhamun, colloquially known as King Tut, was the 12th pharaoh of the 18th Egyptian dynasty, in power from approximately 1332 to 1323 B.C.E.

Tutankhaten was just nine years old when he assumed power, and died at age 19 from a gangrene infection—possibly the result of a broken leg.

The outbreak of World War I delayed Carter’s search for King Tut’s tomb by several years, until the fateful day finally arrived in 1922.

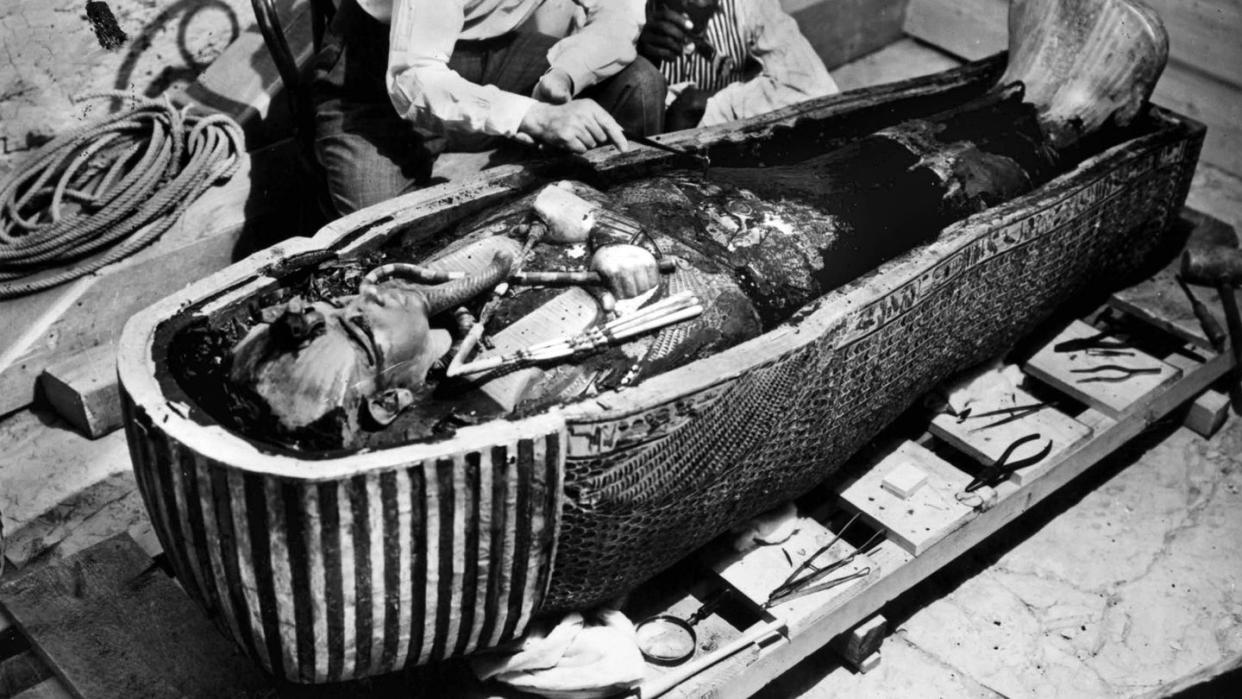

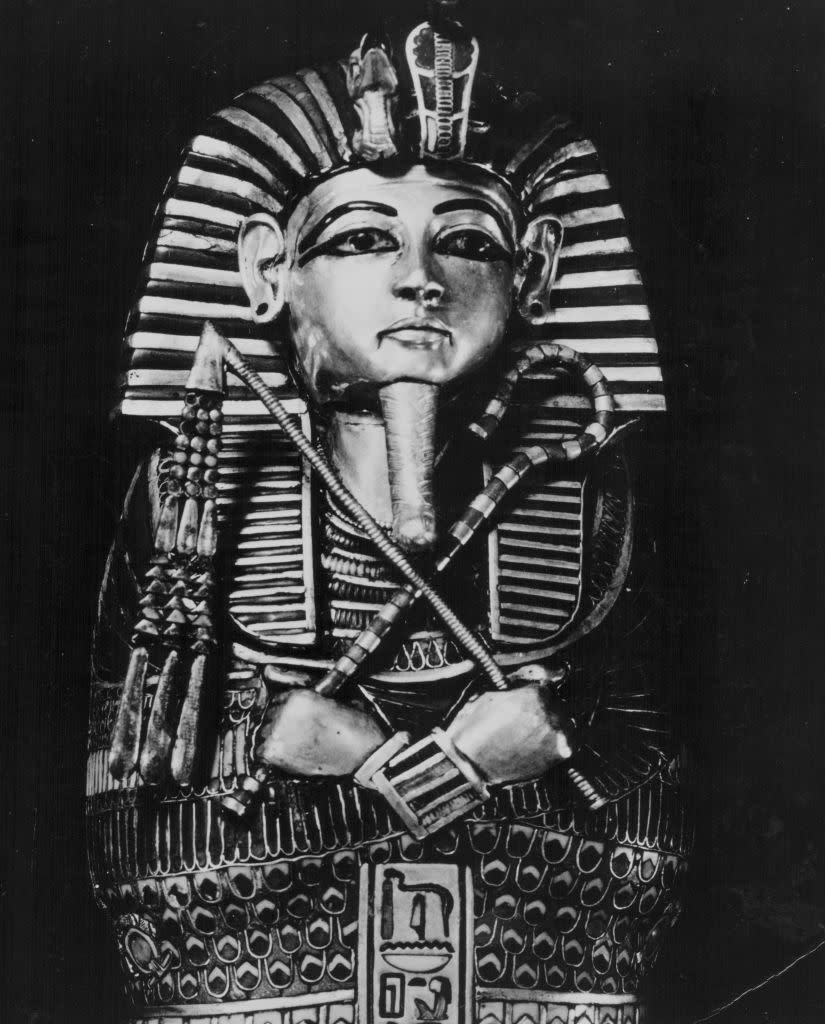

“On November 4, 1922, a boy who worked as a water fetcher on the excavation started to dig in the sand with a stick. He found a stone step and called Carter over. Carter's crew found a flight of steps that led down to a sealed door and a secret chamber. On November 26, 1922, Carter and Lord Carnarvon entered the tomb, where they found an immense collection of gold and treasures. On February 16, 1923, Carter opened the innermost chamber and found the sarcophagus of King Tut.”

It was the discovery of a lifetime: a fully intact tomb, the likes of which had never been discovered before. But for many of the team members, this historic find came at the ultimate price: their lives.

What Is the Mummy’s Curse?

It’s indisputable that, for some of those connected to the exploration of King Tut’s tomb, death arrived under tragic and sudden conditions. Among the most notable was the expedition’s financier, who met an untimely end after a seemingly innocuous incident turned fatal.

Lord Carnarvon suffered a mosquito bite while in Egypt, and one day during shaving, he accidentally cut the bite, leading to an infection. He succumbed to blood poisoning on April 5, 1923.

While no proof ever linked Carnarvon’s death to a supernatural “curse,” the odd circumstances and timing of his passing sparked a captivating story that quickly captured the public’s fascination.

Just two weeks before Carnarvon’s untimely demise, Marie Corelli, an English novelist, wrote a letter cautioning the Lord that “the most dire punishment follows any rash intruder into a sealed tomb,” citing “a rare book” in her possession. That letter found its way into the New York World, the workplace of John L. Balderston, who would one day write the screenplay for The Mummy.

Building upon the supernatural buzz, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle began to weave tales of Egyptian curses into his spiritualism lectures. He further stoked the flames of the curse theory by attributing Lord Carnarvon’s premature death to an “elemental” tasked with protecting King Tut’s tomb.

As storytellers, Corelli and Doyle crafted the narrative of a curse as the cause of death. And soon, others kept adding more characters to the story. As film historian Paul M. Jensen observes in the documentary Mummy Dearest: A Horror Tradition Unearthed:

“If anybody died who was even distantly related to anybody who was around when the tomb was opened, this would be news. This would be indirect evidence of the curse at work.”

Several other untimely deaths tied to King Tut’s tomb fueled the notion of a curse.

George Jay Gould I, the son of railroad robber Jay Gould, passed away from fever on May 16, 1923, following his visit to the tomb, with some blaming the curse for his illness.

A.C. Mace, a member of Carter’s excavation crew, died from complications of pleurisy and pneumonia on April 6, 1928.

Captain Richard Bethell, who worked as Carter’s secretary, was smothered to death while in bed at a Mayfair club on November 15, 1929. Theories around his mysterious death ranged from the curse’s vendetta to accusations involving Satanists.

Adding to the legend of the mummy’s curse is the strange tale of Sir Bruce Ingham, a friend of Carter’s. After using a mummified hand he received from Carter as a paperweight, his house mysteriously burned down.

Conspiracy theorists have attempted to connect Carter’s own death to the alleged curse’s influence, despite Carter succumbing to lymphoma on March 2, 1939—16 years after the presumed curse claimed its initial victim.

But it didn’t really matter how the math worked out. This notion of a curse was so influential that after Lord Carnarvon’s death, Benito Mussolini, who had a gifted mummy on display, ordered its removal to avoid a brutal death at the hands of an ancient curse.

The legend of the mummy’s curse outlived the spiritualist mania of the early 20th century, kept alive through films and novels looking for a horror hook. It was embraced by those espousing xenophobic views toward the Egyptians, as well as by critics of British colonial grave-robbing, serving as a potent metaphor for the era’s transgressions. And as a very different Hollywood movie, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, would wryly observe about the way we like our history: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

The Legacy of King Tut’s Tomb

The Western world’s obsession with Ancient Egypt, known as “Egyptomania,” wasn’t sparked solely by Howard Carter’s famous discovery of King Tut’s tomb, and didn’t fade with his passing. Despite—or maybe even fueled by—the tales of a curse linked to disturbing the tomb, the public eagerly gathered to witness King Tut’s relics whenever they were exhibited across the country.

When The Treasures of Tutankhamun toured the United States in the late 1970s, actor Steve Martin crafted a satirical novelty song for Saturday Night Live that lampooned the crass commercialism that was intricately tied to the discovery and display of King Tut’s treasures. It contained lines like, “Now, if I’d known/They’d line up just to see you/I’d trade in all my money/And bought me a museum,” and the biting, “He gave his life for tourism.”

Today, displays of ancient remains continue to turn a profit. A recent touring exhibition, “The Mummies of Guanajuato,” raised modern safety concerns that could shed light on a scientific basis for the century-old concept of a “mummy’s curse.”

As PopMech previously reported, there’s a proper protocol for displaying mummies that requires precise sealing–a system experts worry “The Mummies of Guanajuato” tour may have disregarded. This protocol’s purpose is clear: to protect visitors from Aspergillus flavus, a fungal mold from ancient tombs that poses a serious threat to lung health.

In 1973, a glaring example of this mummy-adjacent infection unfolded when explorers entered the tomb of King Casimir IV in Poland. Within months following the visit, 10 out of the 12 visitors to the tomb, which had been sealed since the 15th century, tragically passed away.

Aspergillus flavus can damage the immune system, working its way from the lungs to the rest of the body. While it can’t be proven that this specific fungus infected the now long-dead men associated with the curse of King Tut, some have noted that Carnarvon, Gould, and Mace all displayed symptoms consistent with an infection from Aspergillus flavus.

Throughout his life, Howard Carter remained skeptical of curses. While the literati of London attributed those untimely deaths to evil spirits, the self-taught son of a painter called that all “tommy-rot.” Of his role in such myth-making, Carter declared, “the sentiment of the Egyptologist... is not one of fear, but of respect and awe... entirely opposed to foolish superstitions.”

A century later, what would Carter think, not of curses, but of a fungus lying dormant, waiting to latch onto those who burst into sealed tombs that were never intended to be opened? And how does Carter’s notion of “respect and awe” reconcile with artifacts taken from an occupied country, now displayed in museums of former colonial nations and paraded worldwide in commercial exhibits?

Perhaps the more frightening reality of what befell Carter and his men isn’t that an ancient curse punished them for their tenacious exploration. Rather, maybe it’s that through a disease picked up during a plunder for profit, these men, in effect, gave their lives for tourism.

You Might Also Like