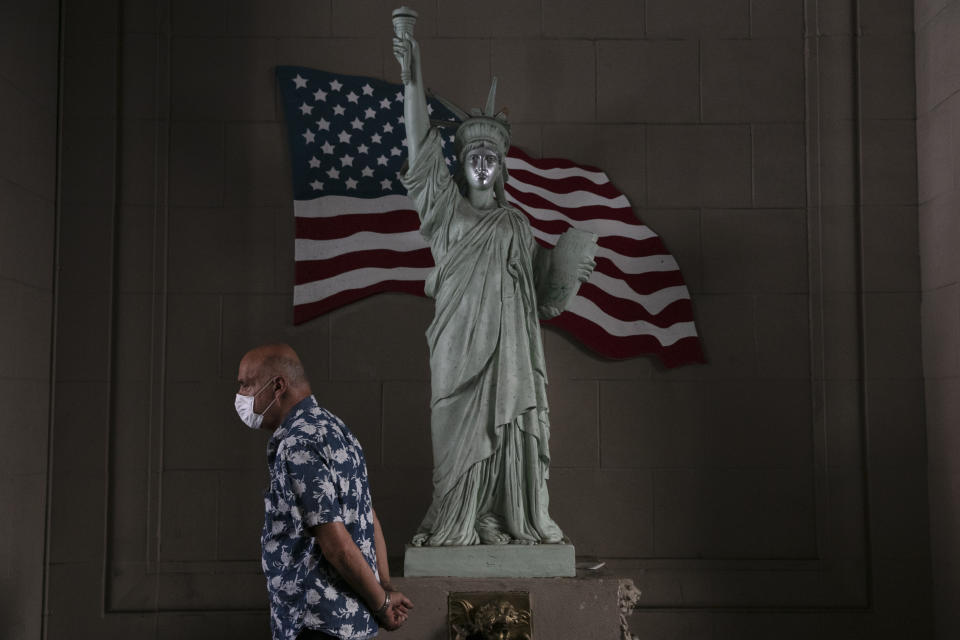

In troubled times: Independence Day in a land of confusion

It was the worst of times. It was the weirdest of times.

It was a season of sickness and shouting, of defiance and tension, of industrial-strength falsehood and spin. It was a moment of ugliness and deep injustice — and perhaps, too, a moment when the chance for justice felt nearer than ever before.

On Independence Day, we Americans — if there is in fact a “we” in American life — celebrate the anniversary of a time when a lot of people, feeling really angry and scared, decided to do something about it that changed the world forever. This year, we mark that event in a year when a lot of people are feeling really angry and scared. Some of them are trying to do something about it, hoping it will change the world forever.

COVID-19 resurgent in 40 of 50 states. The death of George Floyd, the fight for racial justice, and the reactions against it. The fractious politics of masks. A national conversation — loud, enraged and anguished — about the place that a history blemished by ugliness should hold in the present. An uneven president embraced by millions and despised by millions. And superimposed over it all: a sure-to-be-chaotic election season that has only just begun.

Irritable, overstressed, buffeted by invisible forces and just plain worn out, the United States of America on its 244th birthday is a land of confusion.

“At this moment, we are a country profoundly at odds with our own history. We’re seething,” says historian Ted Widmer, author of “Lincoln on the Verge,” which chronicles the 16th president’s journey to his 1861 inauguration weeks before the Civil War began.

“There’s this feeling that there are multiple versions of a country that is really supposed to be one country,” Widmer says. “People are finding it hard to figure out which America is going to survive over the other one.”

This past week, the Pew Research Center found only 12% of Americans satisfied with the way things are going in their country — down from 31% in April, which was already a month into the coronavirus pandemic. The poll was conducted June 16-22 among 4,708 adults, most of them registered voters.

This country has always contained multiple versions of itself. That’s part of what's held it together — “e pluribus unum,” or “out of many, one” — but also part of what’s driving today’s unraveling. One group’s story of America — a story of triumph and exceptionalism and always prevailing — is very different from that of others, which include narratives of abuse, subjugation and systemic slavery.

Many things make this particular Fourth of July different, though.

It comes after millions of Americans have been forced to marinate in their own juices for months, stuck at home, in some cases losing their jobs, being economically stressed, fearing a horrifying death, feeling both trapped and unable to access the “normal” life they remember.

“The ordinary flow of daily life — all of that has been disrupted. Every day looks more similar than it did before,” says Jennifer Talarico, a psychology professor at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania who researches the role of emotion in how people remember events.

The weirdness, she suspects, also reflects the new ways we have to share and amplify things at lightning speed: Could more sources of information be intensifying things? Could we be feeling more because we’re stuck inside with our screens for company?

Today, on a holiday that celebrates the dawn of the United States, recent weeks’ protests hint at an important question: How do you grill burgers and set off flag-colored fireworks but not engage with the actual racial history of the nation and its birth?

There are those who say: Put it aside for the day and just celebrate what the country means — American ideals of equality. But an increasing number of voices are insisting that the discussion has been put aside for far too long.

To Fred L. Johnson III, a U.S. historian at Hope College in Michigan who studies slavery, race and the Civil War, the notion of marking Independence Day without digging into what it means — including the compromises the founders made to appease the pro-slavery South — is ludicrous.

“The very things they were complaining that the British were doing to them, they were doing the same thing — oppression — to Black people early on,” he says.

“Being an American citizen is like having a relationship,” Johnson says. “If all you can do is accept the good parts of the relationship and can’t deal with the hard stuff, I question the sincerity of your relationship. We need to look at the warts, the dark spots and all.”

No one would question whether American life on this Independence Day — after the dawn of coronavirus, after the ascent of a nationwide movement, at the cusp of a volatile election — is different from the previous one. Many are dead. Many more are confused. Many are deeply angry at each other and at the system. Many are terrified. Many have simply had enough.

On the national birthday, bang and whimper are fighting it out as never before. The country, collectively, is a driver without a map.

“When you can’t make sense of what’s going on in the world, life feels pretty meaningless,” says Daryl Van Tongeren, co-author of “The Courage to Suffer: A New Clinical Framework for Life’s Greatest Crises.”

“This holiday extols our way of life,” he says. “This is absolutely an emphasis of the exact American values which are under question, and are under question because they’re not holding up to reality. The curtain’s been pulled back. And people feel like a lot of this is not working anymore.”

That might explain a meme circulating among weary Americans in the past few days. “Dear July,” it says, “I don’t want any trouble from you. Just come in, sit down, don’t touch anything and keep your mouth shut.”

___

Ted Anthony, director of digital innovation for The Associated Press, has been writing about American culture since 1990. Follow him on Twitter at https://twitter.com/anthonyted