A ‘turkey’ in a fur bikini: Raquel Welch and the making of One Million Years BC

In her seminal 1964 essay “Notes on Camp”, Susan Sontag defined camp as “its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” Had she waited another two years, she might have added another example: that of the actress Raquel Welch, who has died aged 82, fighting dinosaurs while wearing a fur bikini in the film One Million Years BC.

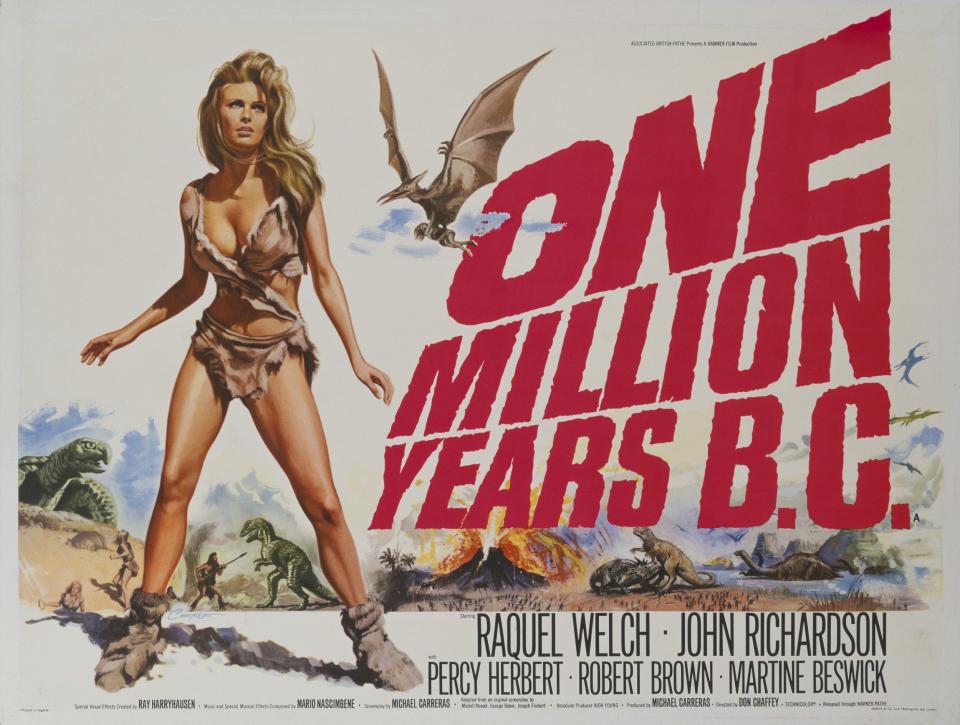

The film’s promotional poster is almost better-known than the picture that it sold: Welch, clad in the aforementioned bikini, stands legs akimbo, as a pterodactyl flutters tamely in the background and gigantic text announces the film’s title. It was used as a plot point in The Shawshank Redemption, helping to conceal Tim Robbins’s painstakingly elaborate escape preparations, and has graced a million walls since its release.

The film that it promotes has always been reduced to that single, iconic image. Upon its release in late December 1966, it was a substantial commercial hit, largely on account of Welch’s stardom and the novelty factor of the combination of scantily clad film stars of both sexes and then-cutting edge Ray Harryhausen-animated dinosaurs. Yet nearly 60 years after its initial release, it has acquired cult status, thanks to both its ahistorical absurdity and the screen-scorching charisma of its lead, in her most iconic role.

By the mid-Sixties, Hammer Films were synonymous with adult-oriented horror films, usually based around Frankenstein and Dracula and starring Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee or both. Yet its founder Michael Carreras believed that there was greater commercial possibility than in making pictures that the BBFC had hissed were, in the case of the horror film X The Unknown, fixated on “shots of 'pulsating obscenity', hideous scars, hideous sightless faces, etc, etc.”

Instead, Carreras looked at the success that bigger-budgeted Hollywood epic films had enjoyed, and produced the H Rider Haggard adaptation She in 1965. It starred former Bond girl Ursula Andress, along with Hammer regulars Cushing and Lee, and revolved around British explorers’ quest for a lost African realm governed by a beautiful and immortal queen. It was a substantial box office hit, and Carreras looked for his studio’s next project, which would combine the elements that had made She a success – a photogenic female lead, exotic locations and an action-adventure storyline – with cutting-edge special effects.

He alighted on a remake of the 1940 American fantasy film One Million BC, which starred swords and sandals stalwart Victor Mature as a caveman who strove to bring peace to warring tribes. The film’s blithe lack of historical accuracy could be noted from the appearance of horror veteran Lon Chaney Jr – “the man of a thousand faces” – as Mature’s father, and the casting of Twentieth Century Fox’s so-called ‘Ping Girl’ Carole Landis as Loana, Mature’s love interest.

It had been moderately successful commercially and was nominated for two Oscars for special effects and musical score, but, a quarter of a century later, was all but forgotten. Therefore, in Carreras’s eyes, it was ripe for revisiting for an audience who would be unfamiliar with the original. But it would need a star offering greater sex appeal than the admittedly superb Lee and Cushing. Who could fulfil such a brief?

Unsurprisingly, given the success of She, the first choice for the beefed-up role of Loana – the lead in this incarnation of the picture – was Andress once again. However, to Carreras’s dismay, she turned down the part, citing a mixture of work commitments and dissatisfaction with Hammer’s far from generous salary offer. So Carreras had to find another star who was less demanding than Andress, but would nevertheless enjoy the name recognition that would bring audiences to the box office. And, it had to be said, look good in a fur bikini.

It just so happened that Raquel Welch, a then 26-year old starlet from Chicago, had come to Hammer’s attention thanks to her role in the 1966 hit sci-fi picture Fantastic Voyage, in which she played the female lead. Although it had not yet been released by the time that One Million Years BC began pre-production, there was enough buzz around her performance, to say nothing of appearance – Bosley Crowther, in the New York Times, called her “a newcomer who is the most pneumatic-looking thing in a skin-diving suit that has yet appeared on the screen” – to justify her casting.

The rest of the cast and crew came together quickly. It was directed by Don Chaffey, who had enjoyed a hit with the similarly-themed Jason and the Argonauts three years before, and the Mature role would be taken by John Richardson, who had played a similar part in She. But, as with Andress, there was no question of his upstaging the female lead. This was to be Raquel Welch’s showcase, and nothing – co-stars; Harryhausen’s dinosaurs; even the barely-there costume – could overshadow her.

Many years after the film’s release, Welch regarded the picture that catapulted her to fame with mixed feelings. She was under contract to Twentieth Century Fox, which had made Fantastic Voyage, but was lent to Hammer for One Million Years BC. Her first reaction to the offer of the project was “It was a dinosaur movie, and I thought ‘I don’t want to make a dinosaur movie’, but [Twentieth Century Fox head Darryl Zanuck] said ‘You have no choice, dear, you’re under contract.’”

She dolefully reflected that “I’m caught in sci-fi hell” after Fantastic Voyage and then its follow-up. As she described it, “first, I had to travel through the human bloodstream at microscopic size, and now I have to fight off dinosaurs.” She further grumbled: “I’m sure that Lana Turner never started her career like this.”

Yet Welch was lured in by seeing an issue of Time magazine, which was promoting then-Swinging London; as she said, “everything was happening in London…there was a whole cultural revolution, with Carnaby Street and all the rest of it.” She decided upon a strategy. “I’ll go to London, I’ll do this turkey, and then everyone will forget about it, and I’ll have myself a great time.”

Unfortunately for Welch, things were nowhere near as simple as that. The production did not come close to the streets of Swinging London – which, in 1966, did not bear a vast amount of resemblance to prehistoric Earth – and instead took place on the Canary Islands. As Welch glumly said: “It was snowing… freezing, freezing cold, and I got the worst case of tonsilitis… They used to be a little bucket of coals under the camera to warm it up, but I was out there with hardly anything on.”

Nor was the script – written by Carreras – a challenge for her thespian skills. “I was trying to embellish my part with little subtleties, but it never turned out that way.” It did not help that the screenplay was rudimentary in the extreme; dialogue consisted of exchanges like “Me Loana!” “Tumak!” Yet, as she later acknowledged, “they were probably better off, because I was pretty green, and I’m not sure that my ideas would have worked out anyway.”

These suggestions were met with Chaffey with seasoned scepticism. As Welch recalled: “I used to rush over to the director and say ‘I have this idea!’, and he’d say ‘Puh-leeze darling, I don’t want to hear any ideas. You see rock A over there? You start at rock A, and you run to rock B, and in the middle, you imagine that you see a giant turtle coming over the hill, and you scream.” Welch acknowledged that Harryhausen’s special effects – less celebrated than his work on Chaffey’s Jason and the Argonauts, but still ground-breaking – made him “a genius in that area”, but sniffed “I could see the appeal of that kind of film, but it took me years to live it down.”

As for her famous costume, it was designed by the theatrical costumier Carl Toms, who regularly worked on Hammer productions. As he later said, “[Welch] had such a perfect body that I took a very soft doe skin, we stretched it on her and tied it together with thongs.” In her recollection, “Carl just draped me in doe-skin, and I stood there while he worked on it with scissors.”

It has been described as nothing less than “the definitive look of the Sixties”, campily combining then-cutting edge fashion with the barest nod towards the film’s setting, and the publicity photographs of her wearing the fur bikini became the greatest sensation since Betty Grable’s heyday in the Forties.

Welch later posed for the photographer Terry O’Neill in the outfit, but one picture – of her hanging from a crucifix in the attire – combined the sacred and profane rather too daringly for Hammer’s publicity department. The image was not shown until a Sunday newspaper published it in the Nineties.

Welch subsequently summed up her work on the picture by calling it “too silly.” Much to her chagrin – and aided by the promotional poster, the photograph of which was taken on set, with Welch virtually unawares – it became her iconic role. It established her career but also led to typecasting in vacuous roles, which she attempted to combat by appearing in edgier pictures such as the Gore Vidal adaptation Myra Breckinridge.

Still, she was never entirely successful in escaping from her first star-making picture. One Million Years BC was a huge box office success, making $8 million in the United States alone, and is today fondly regarded as a cult classic, sacrificing even the slightest iota of historical credibility in favour of spectacle and fun.

And Welch, for all her reservations about the picture, looked back on it with relative fondness decades later. As she said in 2002, “Everybody knew who I was, and I became a star…but not just a star, but a sex symbol.” She had mixed feelings about her new-found fame – “part of me loved it and thought it was the greatest thing ever, and part of me thought ‘I’m not sure I like this – nobody was supposed to see this movie!’”

The film was not something that she regularly revisited, but she still acknowledged its strengths, albeit reluctantly. “For what it was, it was a big hit movie, and God knows, it put me on the map. So I’m very grateful I did that silly dinosaur movie all those years ago.” In the Sontagian definition of the term, its love of the unnatural, of artifice, and exaggeration continues to give pleasure to all of the late, great Welch’s admirers, six decades later.