As virus lockdown eases, Italy ponders what went wrong

ROME (AP) — As Italy prepares to emerge from the West’s first and most extensive coronavirus lockdown, it is increasingly clear that something went terribly wrong in Lombardy, the hardest-hit region in Europe’s hardest-hit country.

Italy had the bad luck of being the first Western nation to be slammed by the outbreak, and its total of 26,600 fatalities lags behind only the U.S. in the global death toll. Italy’s first homegrown case was recorded Feb. 21, at a time when the World Health Organization was still insisting the virus was “containable” and not nearly as infectious as the flu.

But there's also evidence that demographics and health care deficiencies combined with political and business interests to expose the 10 million people in the northern Italian region of Lombardy in ways unseen anywhere else, particularly the most vulnerable in nursing homes.

Virologists and epidemiologists say what went wrong there will be studied for years, given how the outbreak overwhelmed a medical system considered one of Europe’s best. In neighboring Veneto, the impact was significantly more controlled.

Prosecutors are deciding whether to lay any criminal blame for the hundreds of dead in nursing homes, many of whom aren't even counted in Lombardy’s official death toll of 13,325.

By contrast, Lombardy’s front-line doctors and nurses are being hailed as heroes for risking their lives to treat the sick under extraordinary levels of stress, exhaustion, isolation and fear.

Even after Italy registered its first homegrown case, doctors didn’t understand the unusual way COVID-19 could present itself, with some patients experiencing a rapid decline in their ability to breathe.

“This was clinical information we didn’t have,” said Dr. Maurizio Marvisi, a pneumologist at the San Camillo private clinic in hard-hit Cremona.

Because Lombardy’s intensive care units were filling up within days of Italy’s first cases, many primary care physicians tried to treat and monitor their patients at home, even putting them on supplemental oxygen. That strategy proved deadly, since many people died at home or soon after being hospitalized, having waited too long to call an ambulance.

Italy was forced to rely on home care in part because of its low ICU capacity: After years of budget cuts, Italy went into the emergency with 8.6 ICU beds per 100,000 people, below the average of 15.9 within the developed countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

As a result, Italy’s primary care physicians became the front-line filter of COVID-19 patients, an army of mostly self-employed general practitioners who work outside the public hospital system.

Since only those showing strong symptoms were being tested because Lombardy’s labs couldn’t process any more, these family doctors didn’t know if they themselves were positive, much less their patients.

The doctors also had no guidelines on when to admit the sick or refer them to specialists and didn’t have the same access to protective equipment as hospitals.

Some 20,000 Italian medical personnel have been infected and 150 doctors have died.

Two days after Italy registered its first case in the Lombardy province of Lodi, sparking a quarantine in 10 towns, another positive case was registered more than an hour’s drive away in Alzano in the province of Bergamo.

By March 2, the Superior Institute of Health recommended Alzano and nearby Nembro be sealed off like the Lodi towns. But political authorities never implemented that recommendation, allowing the infection to spread for a second week until all of Lombardy was locked down March 7.

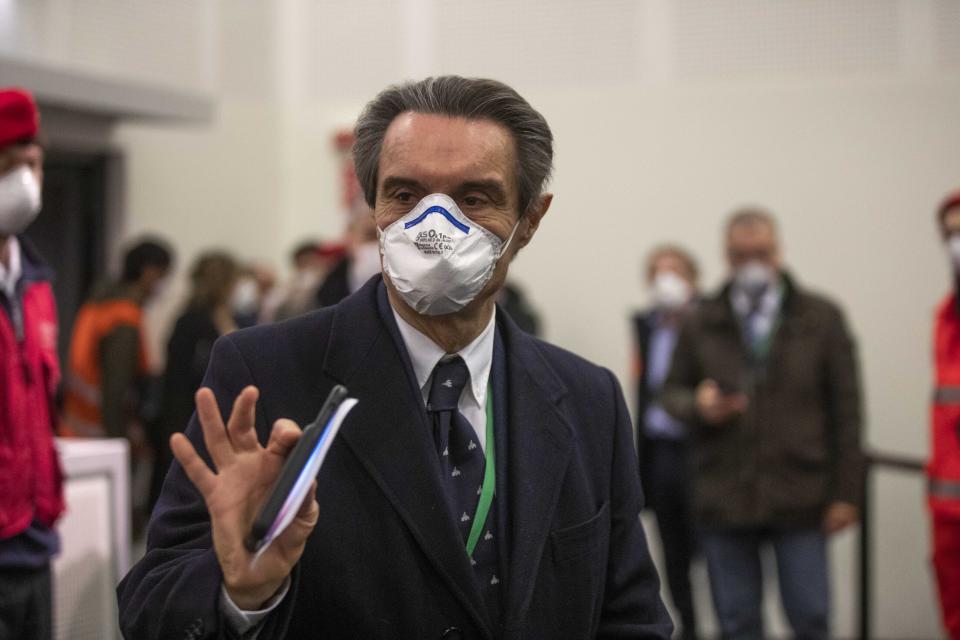

Asked why he didn’t seal off Bergamo province sooner, Premier Giuseppe Conte argued that Lombardy’s regional government could have done so on its own. Lombardy’s governor, Attilio Fontana, said if there was a mistake, ‘’it was made by both. I don’t think that there was blame in this situation.’’

Lombardy has one-sixth of Italy’s 60 million people and is the most densely populated region, home to the business capital in Milan and the country’s industrial heartland. Lombardy also has more people over 65 than any other region, as well as 20% of Italy’s nursing homes, a demographic time bomb for COVID-19 infections.

“Clearly, with the benefit of hindsight, we should have done a total shutdown in Lombardy, everyone at home and no one moves,” said Andrea Crisanti, a microbiologist and virologist advising Veneto's regional government. But he acknowledged how hard that was, given Lombardy’s outsize role in Italy's economy.

“Probably for political reasons, it wasn’t done,” he told reporters.

Unions and mayors of some of Lombardy’s hardest-hit cities now say the country’s main industrial lobby group, Confindustria, put enormous pressure on authorities to resist production shutdowns, claiming the economic cost would be too great in a region responsible for 21% of Italy’s GDP.

On Feb. 28, a week into Italy’s outbreak and well after more than 100 cases had been registered in Bergamo, the province’s branch of Confindustria launched a social media campaign aimed at reassuring skittish investors. It insisted the outbreak was no worse than elsewhere and that production in provincial steel mills and other industries were unaffected.

Even after the national government locked down all of Lombardy March 7, it allowed factories to stay open, sparking strikes from workers worried that their health was being sacrificed.

“It was a huge error. They should have taken the example where the first cluster was found,” said Giambattista Morali of the metalworkers’ union in the Bergamo town of Dalmine.

While the regional government focused on finding new ICU beds, its testing capacity lagged and Lombardy’s nursing homes were left to fend for themselves.

Of particular attention to Milan prosecutors investigating deaths in care facilities was the March 8 decision by the regional government to allow recovering COVID-19 patients to be housed in nursing homes to free up hospital beds.

Another regional decree March 30 told nursing home directors to not hospitalize sick residents over 75 if they had other health problems and avoid further risking their health during transport.

___

A previous version of this story corrected the spelling of Attilio Fontana's first name.