How to Visit Endangered Orangutans in the Leuser Ecosystem in Sumatra, Indonesia

Long ago, there lived an ape. The ape had babies, and those babies grew up and had babies of their own, and over time their descendants drifted apart to the point that they could no longer be considered one type of ape, but five. All were highly intelligent, but one was smarter than the rest. With its gift of speech, this super-smart ape gave the others names: “gorilla,” “chimpanzee,” “bonobo,” and “orangutan.”

This intelligence, however, came at a cost. Though this talking ape was capable of creating wonders, it was also capable of destroying them. Among the wonders it destroyed were many of the forests in which the other apes lived. One such forest is on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, where members of a unique species of orangutan are clinging to what little remains of their native habitat. Last summer, feeling less confident than usual in the merits of my own species, I went to Sumatra myself, hoping to meet one of these survivors. My destination was the Leuser Ecosystem, a sprawl of jungle in the north of Sumatra, the westernmost of Indonesia’s more than 16,000 islands. Orangutans once lived throughout Southeast Asia, but today the only two surviving species are confined to the scattered remnants of rain forest on Sumatra and nearby Borneo. The Sumatran orangutans, almost all of the remaining 7,000 of them, live in the Leuser—a nominally protected stronghold of biological diversity that is growing smaller and less biologically diverse each year. Logging, hunting, and the illegal pet trade have all played a part in the orangutan’s demise, but the main culprit is the global demand for palm oil, a commodity often produced on deforested land.

Conservationists warn that the Sumatran orangutan could become the first great ape to reach extinction, with the Borneo species following close behind. Meanwhile, the slash-and-burn conversion of their habitat into palm plantations is helping fill the earth’s atmosphere with excess carbon, threatening the existence of us all. Travelers who don’t want to spend their vacations contemplating such truths may want to give Sumatra a miss. Bali is nice, I hear. But Bali doesn’t have wild orangutans. Or tigers. Or flowers the size of truck tires. Or the vanishingly rare Sumatran rhino. Although Sumatra’s tourism infrastructure is improving, this vast, wild, jungle-clad island remains much less developed than a place like Bali. For a certain kind of traveler, that’s precisely why it’s such an exciting place to go.

On my way to the Leuser I spent a night in Medan, the capital of North Sumatra province, before heading to the jungle the next day. Riding out of town, I found it hard to imagine that in less time than it takes to drive from New York City to Boston, I would arrive at the edge of one of the richest forests in Asia. Medan was a crush of people and motorbikes and trucks and endless rows of street stalls filling economic niches I didn’t know existed. We passed a stall selling only kitchen clocks, another selling only birdcages, and a purse vendor who, lacking a stall, had hung her wares from the sprawling limbs of a tree, prompting my travel companion, Stefan Ruiz, who took the photographs for this story, to make one of his trademark observations: “It’s literally a money tree.”

Finally the traffic thinned and the city faded, and we were rumbling through the palm plantations, acres and acres of them, the tall, spare trees stretching as far as we could see in every direction, in rows as straight as supermarket aisles. Palm oil is the most commonly used vegetable oil in the world, found in snacks, soaps, cosmetics, and a good number of the other products on our shelves, and Indonesia produces more of it than any other country, accounting for about a third of the world’s supply. If there is a money tree in Indonesia, it is the oil palm.

As we neared the forest, I asked our driver, Adi, who didn’t speak much English, if he had seen a lot of wildlife over the years. He started talking excitedly about something called a “mina,” which I assumed was a kind of monkey, or maybe a local word for orangutan. In fact, Mina was the name given by researchers to one particularly notorious orangutan. As a local would later put it, “she had mental problems.” There were rumors that Mina had bitten tourists. It turned out she had a troubled past: captured as a baby, she’d spent years in a cage.Eventually, she was rescued and brought to a rehabilitation center for orangutans in Bukit Lawang, a village on the outskirts of the Leuser rain forest. But by then, her time with humans had taken its toll.

Related: 10 Wildlife Trips Where You Can Get Up Close With the World’s Coolest Animals

The Bohorok Rehabilitation Center closed in the 90s, but several of the orangutans that passed through it still live in the part of the jungle closest to the village, and so do their progeny, who tend to take after them. Considered “semi-wild,” they generally aren’t afraid of people, and some of the guides capitalize on this fearlessness, luring them closer to tourists with fried rice.

Green Hill, a company that organizes jungle treks and runs the village guesthouse where we stayed, doesn’t go in for that kind of thing. Andrea Molyneaux, who manages Green Hill with her husband, is an Englishwoman with a master’s in primate conservation who did her fieldwork at Camp Leakey, on Borneo. The camp was established by the pioneering Lithuanian-Canadian conservationist Birut? Mary Galdikas, who is to orangutans what Jane Goodall is to chimps. Andrea’s motto is painted on a big sign out front: keep wildlife wild.

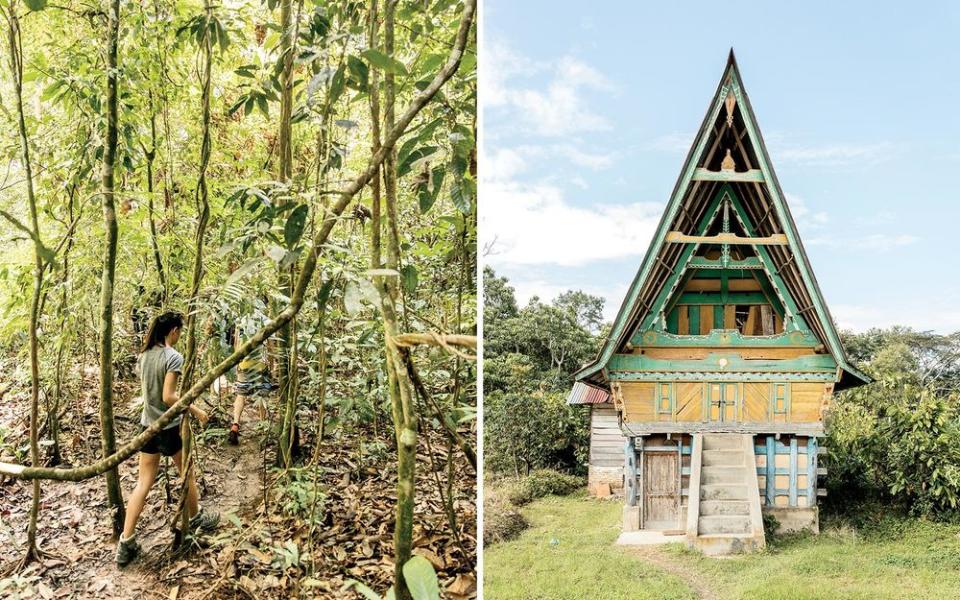

For the most part, Bukit Lawang resembles the other towns in the region—humble concrete buildings with rusty corrugated metal roofs. But at its far end, the road gives way to a footpath that meanders through the trees, and if you follow the path along the river, past the shops selling orangutan T-shirts and orangutan carvings, you’ll find yourself in the hotel district, a sort of fantasy of an Indonesian village filled with guesthouses made with bamboo, jungle logs, and branches.

That night, Stefan and I slept in rustic rooms overlooking the jungle. The next day, we planned to march right into that seething mass of green. We were to spend the morning close to the village looking for semi-wild orangutans, which we were practically guaranteed to see. Then our guides would take us deeper into the forest, to an area rarely visited by people where the foliage would be thicker, the trails rougher, and the wildlife truly wild. We planned to camp there for two nights. If we saw an orangutan in the deep forest, we’d be among the very few people who ever have.

Early the next morning, as the sun rose above trees across the river, we went into the forest. Stefan and I were joined by our head guide, Anto Cebol, his assistant, Ipan, and a pair of college students from Colorado. Anto, a native of Bukit Lawang, is 38, with the long hair and philosophical outlook of someone who has been exposed from an early age to the beliefs and customs of stoned Australian backpackers. Sitting on a boulder, he said, “No one knows how much longer the earth will be.” He smiled defiantly. “Maybe we go to the moon.”

We’d been following him for only a few minutes when he pointed out a troop of black-mohawked Thomas’s leaf monkeys in the trees. Though we were still on easy, well-worn paths, sweat started pouring out of me at a rate I’d never imagined possible. Then we saw it: our first orangutan. This was exciting, of course, that flash of orange in the trees, but she clearly wasn’t wild. She was stretched out on a limb, unafraid and unimpressed. Antol recognized her; he said he knew her mother. As we stood there staring, a long-tail macaque walked right past us, not even bothering to glance in our direction. Then a group of Homo sapiens approached in flip-flops, taking selfies.

So by the time we got on the motorbikes and headed down the road toward a more remote area, I was ready to go a little deeper. After a bumpy ride through palm plantations, we arrived at Bukit Kencur, a hamlet on the edge of the part of the jungle that the Green Hill staff had described as untouched. It was clear that this place didn’t get many foreign visitors. Clusters of reddish palm fruit sat in the dirt outside the sun-bleached wooden huts. The villagers who came over to look at us didn’t attempt to speak English, and no one tried to sell us orangutan carvings or anything else.

One of the villagers approached with a basket of supplies. His name was Chilik, and he was going to serve as an extra guide for the rest of our trip. His training, as I’d later learn, had been unconventional. Some years ago, he got lost in the forest while gathering medicinal plants and sustained himself for five days by watching the orangutans to see which fruits they ate. Chilik didn’t speak any English. Unlike Anto, he wore his hair short, and did not bother with the rubber trekking shoes worn by the guides in Bukit Lawang. He led us through the jungle barefoot, scraping leeches off his ankles with a rusty machete, and he carried most of our supplies on his back in a basket made from rattan vines, which the Bukit Lawang guides had long since abandoned for Western-style backpacks. During snack breaks, he would go off by himself and squat on the forest floor, chain-smoking until it was time to leave.

That first day, we hiked only a short distance, maybe a quarter-mile. Still, it was tough going, as the rest of the trip would be. The trail rose and fell at such a steep incline that we often had to grab at roots and vines just to stay upright. At times it disappeared completely, at which point Chilik would move to the front of the pack and hack a path through the bush with his machete. At last we came to the campsite. It sat on a slope overlooking a picturesque river. As we rinsed off in the cool, clear water, a pair of cooks showed up out of nowhere and built a fire. They boiled a pot of rice, fried some tempeh, sautéed a sackful of tapioca leaves, and whipped up a delicious dish of dried anchovies with wild ginger and chili.

Related: The Top 5 Resort Hotels in Indonesia

We slept beneath a tarp stretched over a frame of lashed-together bamboo poles. The soundscape was a layered mix of cicada, bird, stream, and rain, with a smattering of monkey howls thrown in. We awoke early the next morning, at the first hint of daylight. Toast, eggs, strong Sumatran coffee, then back on the trail, pausing every 15 minutes so that Anto could pass out pieces of leaves and bark, schooling us on the names and medicinal or culinary uses of each species. There was the hot-pink flower of a tree he called assam kimchin. (A lemony herb; goes well with curry). The woody stalk of pasak bumi. (Bitter; defends against malaria). The glossy leaf of the satykop bush. (Per Anto: “To make not broken the first baby when baby is still drinking from mama and mama pregnant.”) On we hiked, our eyes lifted to the treetops, when suddenly Anto saw something that made him break into a sprint. “Mawa!” he shouted, crashing through the foliage. “Lucky!”

Mawa, I knew by then, is the local word for orangutan.

Seeing a truly wild orangutan does feel different from seeing one that has grown up around humans. You see in his eyes that he is frightened, and in his innocence and awe, he reminds you of a child. You feel a rush of nostalgia for your own childhood, when all the world felt like this corner of the forest, mysterious and full of wonder. At the same time, you can’t help suspecting you feel this way primarily because you come from the West, where you and your compatriots, having benefited from centuries of environmentally destructive agricultural and industrial practices, have forgotten the hardships of forest life. This is one of the reasons you can afford to look back at that bygone existence through a romantic lens, much in the way you can afford to romanticize your childhood only after the pain of growing up has receded. You think these things, and you wonder what the orangutan is thinking. And then the screeching ape demonstrates his mastery of simple tools by breaking off a stick and throwing it at you. Knowing what you know about humans, can you blame him?

Eventually the orangutan calmed down and just hung there from the branches staring back at us. Then we heard a rustling of leaves a little way off. “Another one!” Anto cried. Two, in fact—a mother and baby. So that’s why the first one hadn’t fled at the sight of us: he was protecting his family. The mom and baby were moving slowly through the treetops, not leaping like monkeys but plotting a careful course, shifting their weight from foot to foot, and hand to hand.

My last few days in North Sumatra unfolded at a rambling hotel on the shore of Lake Toba, eight hours southeast of Bukit Lawang. At 436 square miles—about the size of Los Angeles—Lake Toba is the largest volcanic lake in the world, and maybe the nicest. The water is sparkling and calm. Soft green mountains rise all around it. The hotel, Carolina Cottages, is a collection of bungalows with sharply peaked roofs and ornately carved wooden fa?ades, a tribute to the traditional building style of the local people. A breeze blew onto the hotel veranda, ruffling the edges of the batik tablecloths. On the beaches, the Coke came in glass bottles and the coconuts came with straws.

At the center of the lake lies Samosir Island, the heartland of the Batak, an indigenous group known for their love of singing. One night, we partied with a crowd of Batak schoolteachers on their summer break. They fed us boiled eggs with chili paste and passed out cups of herbal liquor and brought out a guitar and sang for us and begged us to dance with them and laughed hysterically when we did. Even Stefan, who has been everywhere and isn’t easily impressed, conceded that one of the guests had a solid case when he called Lake Toba “heaven on this earth.”

On my way back to Medan, as I boarded a ferry headed across the lake, a stranger handed me a pocket map. He turned out to be a mapmaker from Java who had traveled all over Indonesia for his work. He told me Toba held a special place in his heart. For years, he said, the Indonesian government had done too little to develop the tourism industry in this provincial outpost, but that was beginning to change. An airport had been built nearby, and there were plans to extend the highway from Medan to the lake. “We want people to know the story of Toba,” he said.

The story of Toba is one worth knowing. The massive volcanic eruption that created the lake some 70,000 years ago nearly wiped out the entire human species—and may have made us who we are today. According to the “Toba catastrophe theory,” originally posited by the science writer Ann Gibbons, the blast plunged the earth into a six-year winter, leaving as few as 3,000 people alive on the planet. Those survivors were the most resourceful of our kind, and they passed on those qualities to their descendants, our ancestors, planting the seeds of human civilization.

It was perhaps because of Toba that our ancestors learned to make fire, and grow crops, and cure diseases, and come up with clever theories about human civilization. And it was perhaps because of Toba that we learned to clear forests, and developed a habit of wiping other species off the face of the earth.

As the ferry pulled into the dock, I said goodbye to the mapmaker and hauled my bags to the driver waiting onshore. Then we began the journey back to Medan, with its truck-clogged streets, passing palm plantations where there used to be forest. With luck, you’ll get to visit one of the forests that remain. If you do, keep your eyes raised to the treetops. You might see someone you used to know.

Plan an adventure in Sumatra

Explore this unsung Indonesian island at the front end of a two-week trip. Its extraordinary natural riches make an ideal prelude to the cultural wonders of Java or the beaches of Bali.

Getting There & Around

Fly to Kualanamu International Airport in Medan via a regional hub such as Singapore. The best way to reach Gunung Leuser National Park and Lake Toba is to hire a car and driver (your hotel can easily make arrangements). Although Sumatra’s tourism infrastructure is getting better, most roads remain rough and crowded, so expect to spend a day traveling to each destination.

Medan

For most travelers, Indonesia’s fourth-largest city is a gateway to the natural attractions of North Sumatra. I arrived after dark and set out for the jungle the next morning, skipping such sights as Our Lady of Velangkanni, an Indo-Mughal-style church, and the museum at Maimun Palace (66 Jl. Sultan Ma’moen Al Rasyid; 62-61-452-4244). I did stick around my hotel, Aryaduta Medan (doubles from $110), long enough to sample a grand breakfast spread that combined American, Chinese, and Indonesian food. Another comfortable option is the JW Marriott (doubles from $58), which has a lovely rooftop pool.

Bukit Lawang

This riverside town at the entrance to Gunung Leuser National Park is where most orangutan treks start. I stayed at Green Hill (packages from $240), a guesthouse where the staff arranges trips into the jungle. For optimum orangutan sightings, those willing to rough it should consider booking a three- or four-day trek.

Lake Toba

After an eight-hour drive from Bukit Lawang, I took a ferry to Samosir Island in the middle of the lake. Lodging at Carolina Cottages (doubles from $12) was basic but comfortable. For a more luxurious stay, try the Taman Simalem Resort (doubles from $87), a group of lodges and private villas overlooking the lake. I recommend a visit to the Huta Bolon Simanindo (Jl. Pelabuhan Simanindo, Samosir Island; 62- 813-9672-1133), a preserved historic village of traditional wooden houses.

Tour Operator

ATJ’s Jarrod Hobson is known in the industry as “the Indonesia guy” and is a long-standing presence on T+L’s A-List of top travel advisors. He can create custom itineraries that combine Sumatra with other islands, such as Java and Bali. atj.com; from $350 per person per day.

What to Pack

You’ll need a powerful insect repellent, sunscreen with a high SPF, a headlamp, a waterproof wallet for your passport and papers, tough hiking boots, and light, long-sleeved shirts and long pants.