Do You Want to Know How You’re Going to Die?

When Heather, a small business owner in Virginia, walked down the aisle at her wedding in October 2015, her mother, Anna, sat in the front row smiling. Heather knew her mom as a “hippy” who wore comfortable clothes like jeans and clogs, but for her daughter’s wedding, Anna had made an exception, wearing a sequin navy dress with low heels. “It’s what you dream of, and I got the chance to have it,” says Heather (not her real name), now 36. “If we had gotten married any later than that, things would have been vastly different.”

Life for Heather and Anna changed quickly—too quickly. Just over a year after her wedding, Heather found out that Anna, 61, had been diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, also known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease, a neurological disorder for which there is no cure. Two and half years later, Heather witnessed her mother starve and dehydrate herself to death; Anna could not bear to live with ALS any longer.

Anna’s ALS diagnosis left Heather with more questions than answers. Her uncle—Anna’s brother—had also died from ALS, in August 2014. With two close familial ties to the disease, Heather worried she, too, may carry the gene. Only a genetic test would reveal the truth. A positive test result would mean that Heather would likely later receive an ALS diagnosis and she could put her unborn children at risk of what she refers to as the “most sadistic disease.” But what would such knowledge give her? There would be nothing she or anyone could do to prevent symptoms from appearing, and she had no way of knowing at what age the symptoms would start. What can a young woman do with the knowledge that she could die in the same cruel manner that her mother did? Is there value in knowing that you have the gene for a disease for which there are no cures or preventative measures you can take to delay its onset? And is there anything that a person can do to change their children’s fate?

When most people think of ALS, they think of the Ice Bucket Challenge or celebrities—mostly white men—associated with the disease. The first famous person to be diagnosed was, of course, Lou Gehrig, a New York Yankees player, who was forced to retire after his diagnosis in 1939 and after whom the disease is now nicknamed. Others may think of Stephen Hawking, the renowned physicist, and a medical anomaly in the ALS community, as he lived with the disease for 55 years.

Today, around 15,000 people in the U.S. are living with the disease. The average person lives two to five years from diagnosis until death. In the majority of ALS cases, the cause is unknown and is referred to as sporadic ALS. But familial ALS occurs in 5 to 10 percent of cases when there is more than one incident of ALS in a family. When a parent has familial ALS, there is generally a 50 percent chance that the gene responsible will be passed on to each child.

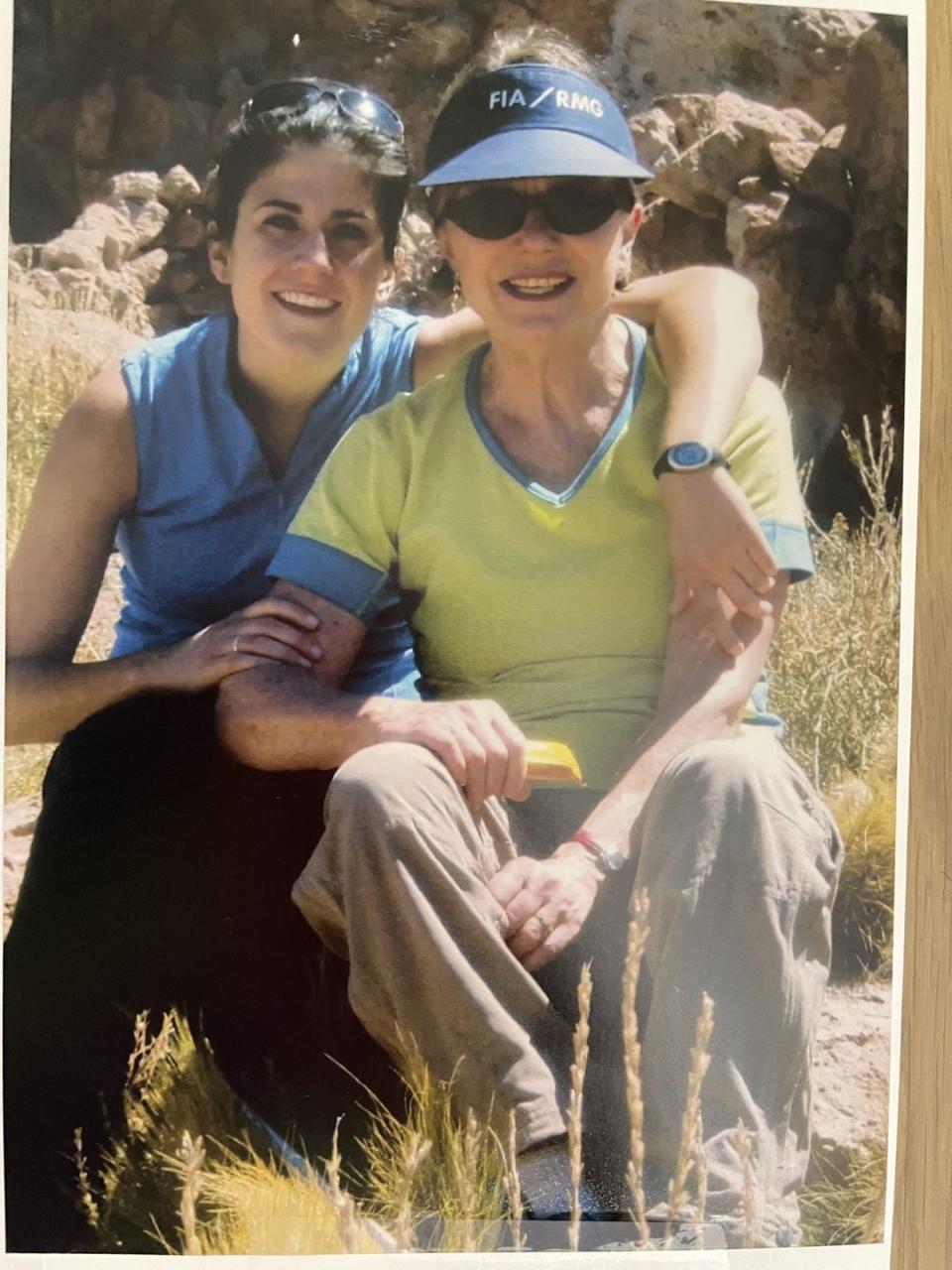

When I think of ALS, I think of my mother. Twelve years ago, I watched my mom take her last breath 17 months after she was diagnosed with the disease. Throughout my life, I watched my mother tell people—usually men—that they were “full of shit.” I saw her ice skate on a frozen canal in Washington, D.C. on the rare occasion it froze; I smiled as she flipped off drivers who tried to cut in front of her as she rushed us to school in the mornings. Then, I watched my mother’s sharp mind listen as she was repeatedly told by neurologists, “No, there is nothing we can do to save you.” After months of listening and of losing the ability to play tennis, talk to friends, or eat, her demeanor changed. She rarely smiled and her communication decreased. In the final months of her life, she had lost so much weight that her body could barely carry her own head. She couldn’t even lift her body to hug me goodbye.

When I learned about my mother’s (sporadic) ALS diagnosis, I knew the disease would kill her and there was nothing I could do. When Heather learned her mother’s ALS diagnosis, she too knew Anna would die from ALS, but also that she and any children she had could very well be at risk of the same fate. Heather became determined to find out if she could have children and not pass the gene on. She spent hours researching online, and discovered there might be a way to do so through in vitro fertilization (IVF). A simple Google search of “Familial ALS IVF'” led her to a thread on Reddit where a woman, with the same ALS gene as Heather, shared that she had successfully used a process called Preimplantation Genetic Testing, or PGD, which can test an embryo for a specific gene condition, to ensure that her baby didn’t inherit the gene. It is now available for most known single gene disorders such as cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, Tay-Sachs disease, and Huntington’s Disease.

Heather’s research provided her with the hope she needed. But to save her unborn child from the risk of ALS, she first had to find out if she was at risk of dying from the disease herself. “I think it goes back to this question: do you want to know how you’re going to die?” Heather says. “There are people that would say ‘yes’ and there are people who would say ‘not a chance.’”

Less than six months after her mother’s diagnosis in March of 2017, Heather sat in a small windowless medical room with her husband waiting for her genetic test results. She had spent weeks searching for a lab that would test her anonymously. Maintaining her anonymity was important to Heather, because she had read online that a positive test result on her medical record could prevent her from obtaining life insurance (which later proved to be true when her real name was mistakenly revealed on a medical chart).

Heather was tested for the C9orf72 (c9) gene, which, in addition to ALS, is responsible for frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and for over a third of familial ALS cases. C9 was identified just three years before Heather’s uncle died, but Heather knew that he had tested positive for that gene. “You’re positive, I’m sorry,” Heather remembers the genetic counselor saying to her before swiftly leaving the office. “She just looked at me basically like, ‘You’re going to die from Lou Gehrig’s, your mom died from Lou Gehrig’s, and have a nice day,’” Heather says.

Tears poured out of her eyes. Given the recent discovery of C9, the number of people with the gene who will later develop ALS is not known, Terry Heiman-Patterson, the neurologist who treated my mother and director of the ALS Center of Hope, told me via email. But according to the ALS Association, most people carrying the C9 mutation will eventually contract the disease.

A month after she received a positive test result, Heather reached out to a local fertility clinic. She started her first round of IVF in December 2017, five months before her mom died. Once Heather’s eggs were fertilized, the embryos were sent to be tested, but none of them were deemed healthy. (Three out of four embryos had the C9 gene, and one had a genetic abnormality.) Five days after her mother died, in May 2018, Heather learned a second and third round of IVF (batched together to reduce costs) had also been unsuccessful at producing healthy embryos.

The emotional toll was unbearable. Heather says she cried alone in the shower, stopped caring about her work, hated the way she looked, and dreading socializing, leaning on her husband and a Facebook IVF and PGD group for support. She was angry at her insurance company for not covering additional rounds of IVF, and overcome with jealousy whenever she saw pregnant women. She tried to force herself to believe that she would be okay if she never had kids, but couldn’t shake her desire to be a mother.

In early 2019, she did a fourth and fifth round of IVF, and in March, she learned she had finally managed to create an embryo without the C9 gene. In July, the embryo was implanted, and in March 2020, she gave birth to a healthy baby girl. Heather said she felt disbelief as she cradled her daughter in the hospital. She couldn’t believe that she was finally holding her child—and that that child would not face the same fate that her mother did, and that Heather likely will. “It’s so important that people can know that, while everyone is searching for a cure, in the meantime, there is actually something that you can do,” she says.

Heather doesn’t share her gene status beyond close family and friends. “When you look at me—and I’m not bragging—but I get told a lot that I’m beautiful, that I have a good-looking family,” she says. “No one would ever look at me and know I’m going to die of Lou Gehrig’s. I don’t want the gene to be my definition.” But she no longer says “someday.” In every aspect of her life, she is trying to live to the fullest.

Though Heather can’t control when or how she will likely experience the first symptoms of ALS, she lives each day knowing that she protected her daughter from what we both know is one of the ugliest ways to die. “I can’t wait to hold her hand and tell her that I did everything I could so that my future was not going to be hers,” Heather says.

The next day, photos of Heather and her toddler daughter, surrounded by snow, wearing puffy winter jackets and matching white winter hats pop up in my Instagram feed. In the second picture, taken by someone standing behind her daughter, I can see Heather’s smile as she stands looking at her little girl. Staring at my phone, I smile too, knowing that Heather’s daughter won’t face the same fate that our mothers did.

You Might Also Like