Wes Studi revisits 'Dances With Wolves' and the changing depictions of Native Americans in film and television

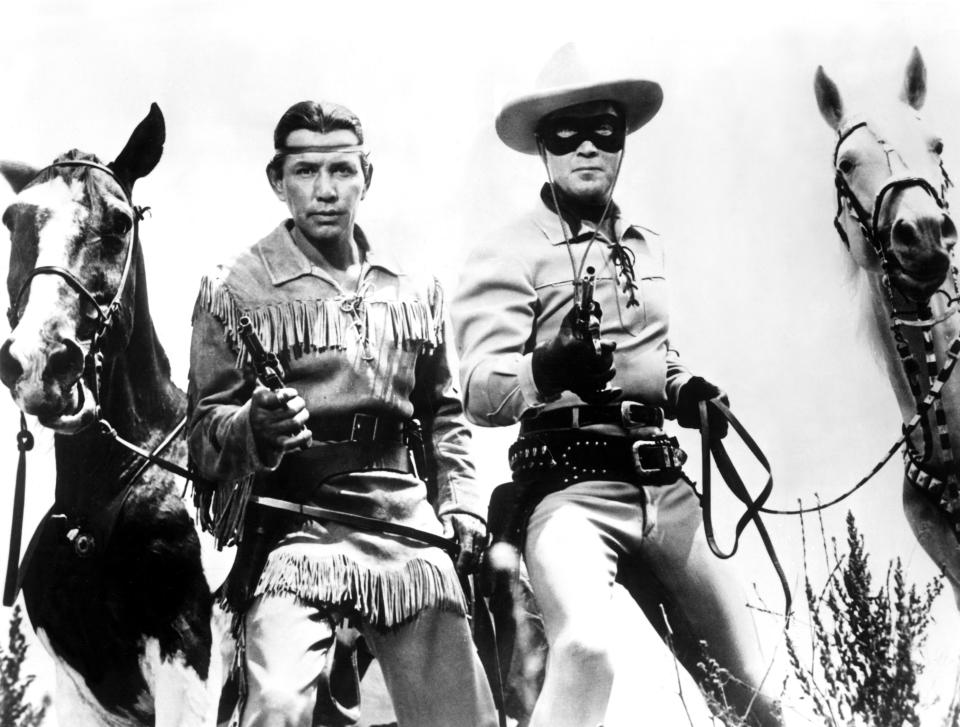

Like many kids who grew up in the 1950s, Wes Studi remembers racing to the television after school and switching on the black-and-white adventures of The Lone Ranger. But he wasn’t tuning in to watch Clayton Moore as the title character. Instead, his eyes were drawn to pioneering Indigenous actor Jay Silverheels, who played the Ranger’s constant companion, Tonto. “That was the first time I ever saw a real Native onscreen,” Studi tells Yahoo Entertainment. “He was one of the few that was actually on screens of one kind or another at that time.” (Watch our Native American Heritage Month video interview above.)

That kind of immediate identification with an actor was something that Studi, who was born into a Cherokee family in Oklahoma in 1947, didn’t necessarily feel when watching big-screen Westerns made by the likes of John Wayne. “I sort of concentrated on the action and the horses,” he says of those movies, which frequently depicted Native Americans as nameless villains to be killed by the stalwart white heroes. But Silverheels — who hailed from Canada’s Six Nations reserve — was regularly part of the action on The Lone Ranger, which fascinated Studi. “I asked my dad, ‘How is he able to do that?’” he remembers now. “My dad said, ‘I don’t know how he did it, but most of the time you have to be six foot tall, blond and blue-eyed to be on television or in the movies.’ And essentially that was the truth! Jay was an outlier avatar of sorts.” (Silverheels died in 1980.)

Decades later, Studi would forge his own path to the screen, one that led him from activism to acting. In his twenties, he participated in the 1973 takeover of Wounded Knee, when members of the American Indian Movement occupied the South Dakota town as part of a sustained protest against the federal government’s handling of Native American affairs. The 71-day occupation brought renewed attention to the plight of many tribes living on underfunded and neglected reservations. “The movement had a huge impact in terms of bringing our cause to the American public,” Studi says now. “It was a great awakening.”

Wounded Knee also captured the media’s attention, which in turn enlisted prominent Hollywood actors like Marlon Brando in AIM’s cause. In the years to come, several activists — including the organization’s leaders Russell Means and Dennis Banks — found their way into the film industry, with the express intention of telling Native stories from a Native perspective. Studi played a small role in one of those stories: 1989’s Powwow Highway, a low-budget road comedy that also offered a compelling contemporary portrait of life on Native American reservations. “It was a really great step forward in terms of Native content in film,” he says now. “All of the characters were Native… it’s a groundbreaking film if you look at it in those terms.”

The year after Powwow Highway, Studi had his first taste of a major studio production when he joined the large cast of Kevin Costner’s epic Western, Dances With Wolves. Released 30 years ago on November 21, 1990, the movie grossed over $400 million worldwide, and won multiple Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. According to Studi, that kind of reception seemed unimaginable during the movie’s production. “It was unfortunately referred to as Kevin’s Gate for awhile,” he says, chuckling. “It was a huge, long story and a lot to people had their knives out about it.”

It wasn’t just the scale of the production that had people nervous. Based on a book by Michael Blake, Dances With Wolves was about Civil War soldier, John Dunbar (played by Costner), who is re-assigned to the remote frontier, where he befriends the neighboring Lakota Sioux tribe led by Graham Greene’s Kicking Bird. Over the course of the movie, Costner is welcomed into their community and helps them fight against enemies ranging from a rival Pawnee tribe (led by Studi) and encroaching white soldiers. That story of a white man who “goes Native” bothered some critics at the time, and gives Dances With Wolves a complicated legacy today. For his part, Studi remains proud of the movie. “At the end of it, Dunbar is not a celebrated man,” he notes. “In fact, he’s kind of an outcast. So I don’t see him as being glorified as a savior of the Lakota or anything like that. He’s a flawed character who did beneficial things, but things were done for him as well.”

While shooting the film on location in South Dakota, Studi remembers being impressed by Costner’s attention to the details of 19th century Native life. “We were shooting right there in Oglala country… [and] he went to great measures to make it as authentic as possible. The Oglala people were advising and consulting on everything, as well as being a part of the picture.” For his role as a Pawnee, Studi learned the tribal dialect via tape recordings. “It would be great if a Navajo could play a Navajo, a Cherokee a Cherokee and a Pawnee a Pawnee,” he says. “But at this time, we say, ‘At least the guy is actually Native!’”

In the wake of Dances With Wolves, Studi scored his breakout role in Michael Mann’s 1992 adaptation of James Fenimore Cooper’s novel, The Last of the Mohicans. As the movie’s Mohawk villain, Magua, the actor made an enormous impression on audiences. “I’ve heard Magua described as one of the great villains in cinema history,” he says, delightedly. “Take that, Joker!” Studi adds that the secret to his performance was not thinking of himself as the bad guy. “Whatever part I have, no matter how small, I always play my guy as the good guy. Michael and I talked about how to dimensionalize him so that we saw more of his pain and humanity. I was really happy with the way Michael shot and edited me as a character.”

The Last of the Mohicans made Studi a permanent fixture on movie and television screens, appearing in both historical tales like Geronimo: An American Legend and The New World and contemporary films like Mystery Men and James Cameron’s Avatar — which has been compared to Dances With Wolves. In a full circle moment, he played a role in the pilot for a modern-day take on The Lone Ranger that aired on The WB as a TV movie in 2003. (Indigenous Canadian actor Nathaniel Arcand played Tonto in that version; Studi portrayed the shaman, Kulakinah.) And in 2019, he became the first Native American actor to receive an honorary Oscar for his contributions to cinema.

Looking ahead, Studi hopes to see more representation for Native Americans on film and television. “I think it’s already happening,” he notes, citing performers like Amber Midthunder and Tantoo Cardinal. “We’re getting to see Natives in contemporary situations and still bringing it as skins — as Indians. It’s never enough, and never soon enough, but we’ve got to live with the world we have.”

The recent presidential election demonstrated to Studi just how far Native Americans have come in the public consciousness... and how far they still have to go. In states like New Mexico, Native voters played a key role in President-elect Joe Biden’s victory, but a widely-circulated CNN poll listing various demographics identified them as “Something Else.” “Here’s the thing about that,” Studi says. “I like the way Native humorists have taken that whole thing and run with it. It’s like ‘Hey, we are something else, and everybody knows it!’ The first thing they ever called us was Indians, and that was a huge mistake back then. ‘Something Else’ is like the equivalent of that in 2020. So CNN has something in common with Columbus!”

Dances With Wolves is currently streaming on Starz.

— Video produced by Jen Kucsak and edited by John Santo

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: