The White Crow review: heartfelt Nureyev biopic that’s light on sex appeal

Dir: Ralph Fiennes; Starring: Oleg Ivenko, Adèle Exarchopoulos, Ralph Fiennes, Chulpan Khamatova, Sergei Polunin. 12A Cert, 127 min.

The White Crow is clearly a labour of love. Inspired by Julie Kavanagh’s superb 2007 biography of Rudolf Nureyev, it centres on the Kirov Ballet’s visit to Paris in the summer of 1961, building up to an impressively tense depiction of the era-defining dancer’s defection to the west at Le Bourget airport on June 16 that year.

However, writer Dave Hare and director Ralph Fiennes also cut constantly and ambitiously between eras: between the “present” in Paris; Nureyev’s birth in 1938 (on a Trans-Siberian train near Irkutsk) and grindingly poor childhood; and his days at the fabled Vaganova Academy in St Petersburg. This is characteristic of a film that goes to almost obsessive – if ultimately only partly successful – lengths in the interests of top-to-bottom accuracy.

True, there’s the odd dash of Nouvelle Vague-ish flamboyance in Paris, but in the main, Fiennes as opted for a hand-held, documentary, almost wilfully shaky shooting style that plunges you into the moment, while Russians are played by Russians, French by French and so on, with people speaking in English only when it’s the characters’ shared lingua franca. The only, if notable exception to this is Fiennes himself, breaking his own rules by co-starring (with a sympathetic combination of authority, weariness and tenderness) as Nureyev’s teacher and mentor Alexander Pushkin, even if he goes a long way towards atoning for this cheeky transgression by speaking in Russian throughout.

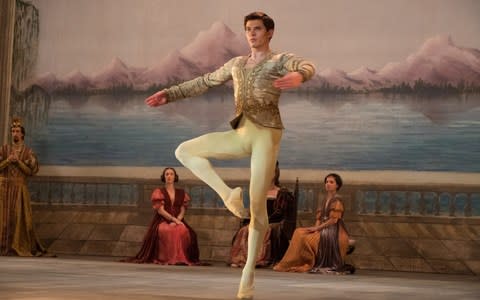

Also crucial to the film’s bid for verisimilitude is the fact that every dancer (again, Pushkin the exception of sorts) is played by a real-life dancer, which gives it a crucial ring of truth, never more so than in the all-important rehearsal scenes. Central to this, of course, is the casting of Kazan-based dancer Oleg Ivenko as Nureyev.

A first-timer to screen acting, and often having to speak in English, Ivenko acquits himself valiantly. Although not in the Nureyev league (though who is?), he dances well, looks like him, and gives a passionate rendering of a burgeoning artist determined to find his voice, not only via dance, but also via his appreciation of the masterpieces in the Hermitage and the Louvre.

But – and this was perhaps always going to be a stumbling-block – Nureyev was a man who could turn every head in a room simply by strolling into it, and that quality is impossible to fake. For all his physical and facial resemblance to Nureyev, and his aptly volcanic outbursts, Ivenko never quite captures the feral, insolent, intensely sexual charisma that came off the great man like steam – but nor does the film quite encourage him to.

We do see him in his Paris hotel room eyeing the bare bottom of fellow Kirov star Yuri Soloviev (Sergei Polunin) in what we assume is post-coital admiration, but there is little or no hint of the physically voracious side of Nureyev that would ultimately lead to his death from an Aids-related ilness in 1993, but which was also inseparable from his blazing presence as a performer. And, although there is a definite spark to the scene in which Pushkin’s wife, Xenia (an excellent Chulpan Khamatova) seduces him, this seems all the older character’s and actress’s doing.

You can’t help wondering what sort of newly kindled fire-behind-the-eyes Polunin might have brought to this encounter had that real-life ballet rebel been cast as Nureyev, while my longstanding fantasy about the young Tommy Lee Jones starring in a Nureyev biopic (they were absolute dead-ringers, from cheekbones to f***-you attitude) will inevitably have to remain just that.

Bound in with this carnal coyness is the film’s refusal to go all-out with presenting Paris as what must have seemed an anything-goes utopia to the young Nureyev and which, on some level, must have helped fuel his desire to defect. Although the after-hours scenes involving Nureyev, Adèle Exarchopoulos’s elegantly drawn socialite Clara Saint et al feel like jolly decent fun, they lack edge: overall a little less chin-stroking art appreciation, a little more thigh-stroking mischief, would have helped.

The result? A serious-minded, often beautiful, utterly heartfelt character study that nevertheless lacks its astonishing protagonist’s fleet-footedness and only partly captures what made him tick.