How Whitney Houston's iconic Super Bowl national anthem became the gold standard

“The Star-Spangled Banner” is known to be one of the most challenging songs for a performer to belt, which is ironic since it was written for every United States citizen to sing. Its wide range has often provided some of the more amusing performances to ever grace a basketball court or football field, from Fergie's to Roseanne's. Still to this day, the national anthem, written by Francis Scott Key and John Stafford Smith, can be a tough one for even the most trained star to do right by.

But then there was Whitney Houston.

In 1991, the then 27-year-old vocalist set the gold standard with her rendition at Super Bowl 25 on Jan. 27. She was at the height of her music career, having released three successful studio albums in the five years prior to stepping onto the football field. The country had just entered the Persian Gulf War and there was a sense of deep patriotism in the air when she performed, something that her rendition upheld to the nth degree.

“If you were there, you could feel the intensity,” Houston, who died in 2012, said during an interview for the accompanying DVD for her greatest hits album back in 2000. “We were in the Gulf War at the time. It was an intense time for our country. A lot of our daughters and sons were overseas fighting. I could see in the stadium, I could see the fear, the hope, the intensity, the prayers going up.”

“It was hope, we needed hope, you know, to bring our babies home and that's what it was about for me. That’s what I felt when I sang that song, and the overwhelming love coming out of the stands was incredible.”

Thirty years later, TODAY had the opportunity to interview Rickey Minor, Houston’s longtime music director, who coordinated that incredible performance.

"It’s easier to stay with the status quo”

“I'm big on never looking back, but then this thing comes up,” Minor, 61, told TODAY. “And we're way back. I feel like I'm the guy in ‘Back to the Future.’ But I love it, and what I really, really love… I really appreciate all of the love that Whitney is getting. I feel like the clouds are opening up and she's rejoicing in her work and her commitment to doing the best job every time.”

Minor joined Houston's band in 1986 and a short time later became the band's music director.Since that era, he has worked with many other major recording artists, including Ray Charles, Beyoncé, Christina Aguilera and Alicia Keys. He also replaced Kevin Eubanks as bandleader on “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno” in 2010, and worked as the musical director for nine seasons on “American Idol.” Despite all those esteemed credits, what the Emmy winner is most widely known for is his working relationship with Houston.

At the time of the national anthem, Minor said “Whitney was in a very creative place, a very open place.”

“Her album had just come out, she had a world tour, she had just done a screen test for ‘The Bodyguard’ and we were busy,” he remembers. “She was vocally at her best for sure, because we were working all the time. So that muscle was being used, but she had it innate. It's crazy to think that someone with a voice like that, never really warmed up because she was just always singing. It's amazing that she was able to do whatever she wanted to do with her instrument. She had total control.”

Not only was Houston’s profound instrument on display that Super Bowl day, but also the actual arrangement of the song which was quite original. This orchestration was something that executives at the NFL, CBS and the orchestra pushed back on in the days leading up to the big game.

“Change is one of the most constant things that happens, yet we resist something that is foreign to us,” Minor said. “This was done the same exact way. Every orchestra in the U.S. knows how to play it by heart, they need no music because it's the same arrangement that's played all over. We were crying to hear a different interpretation of it, yet it is fear, fear of the unknown, fear of what if they don’t like it? It’s easier to stay with the status quo.”

But that status quo is what Houston wanted to change.

The national anthem is in a waltz tempo with three beats to a measure, every three beats a new measure comes. In 1983, a year before he died, Marvin Gaye belted out a soothing rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at an NBA All Star game. “Marvin used a drum machine that made it four, four,” Minor said. “And so that was one of the things that Whitney really loved about that. She asked, ‘Is there any way we can have a little more time like he did?’”

That tempo change made a substantial difference, as did some of the other style modifications that added more jazz and gospel elements to the arrangement specifically created for her.

“John Clayton Jr. really worked in the classical and the jazz world, with a lot of arrangements for Quincy (Jones) and for symphonies,” Minor explained. “He was my bass teacher when I went to college, so this was a relationship that we could work closely together. It's about setting the mood, so we talked about those things that we wanted to give her to use.”

"I work for Whitney, not the NFL or CBS. If she shines, we all shine."

Minor said the first part was “nice and strong,” but that the second verse was created to “get more intimate, so that it can give you someplace to go because if you're just big, big, big the whole time, it doesn't give you a chance to breathe and doesn't give you a chance to bring the people in.”

With some convincing, Minor ended up urging the executives who questioned the new arrangement to let them do what they wanted to do. “You have to trust me,” he said to them. “I work for Whitney, not the NFL or CBS. If she shines, we all shine. Just wait until Whitney sings it, and you will understand it more.”

Houston listened to the track once, maybe twice, before recording something that is known as a pre-record a few weeks before the game, a requirement of large-scale events in case a singer gets sick.

“She never heard it until she sang it for the pre-record, as in all of the Super Bowl and big events like that, they require singers to do a safety vocal,” he said. “That is pretty much that first take and her first time hearing it, which is really unusual. Singers, actors, they always say the first take; that's really the truth. You're reacting to what you're hearing in the moment, rather than trying to craft a perfect vocal.”

The pre-recorded version that is almost entirely from that first take ended up being the audio used on the day of the Super Bowl, despite Houston still singing live on the field. The debate on whether the audio heard was the live performance from that day or a pre-recorded version slightly muddied the waters of the performance’s legacy, since lip-syncing is such a polarizing topic and there were multiple conflicting messages being shared by many of the parties involved in the performance.

“Truth is always the right answer,” Minor said. “I never shy away from someone questioning anything that was done, or how it was done. I mean, the truth is the right thing. Could I have said that it was live-live? Yes, but then when do you stop trying to gloss something over? It is what it is. And there's no doubt that Whitney sang it. So my answer to that, my response to that immediately was, ‘Yes, she sang live. But we used the track for the audio.’”

One of the ways that Minor fought this backlash was coordinating for Houston to open her HBO concert “Welcome Home Heroes" with an a cappella version of the national anthem two weeks later, to prove to the naysayers and critics that she could do what she did at the Super Bowl live.

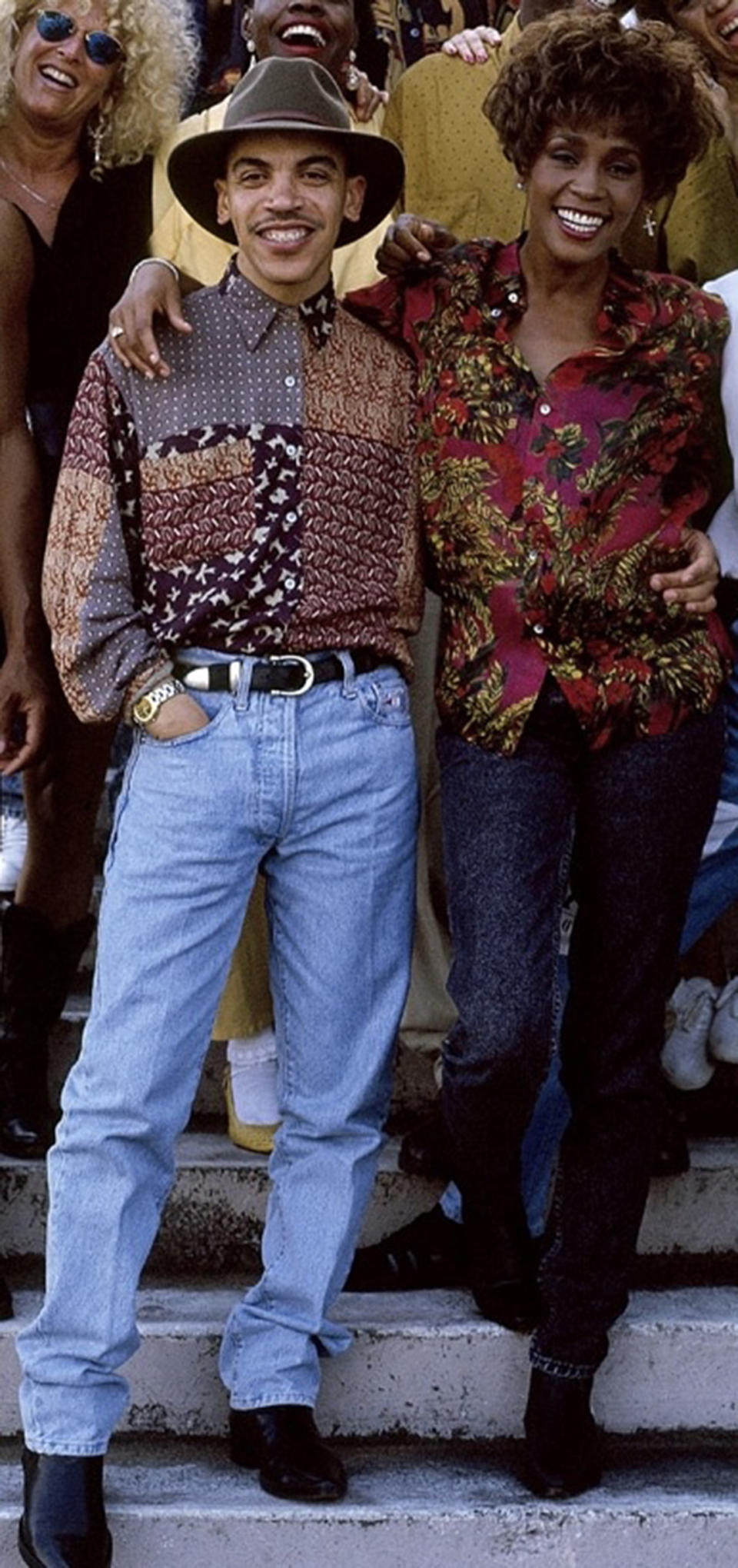

Another facet that made Houston's performance stand out was the fact that she dressed down for the performance.

"Whitney's thing was, she was there to cheer on the New York Giants," Minor said of her decision to wear the white tracksuit and headband. "She was there for that and after she performed she wanted to be comfortable to go and sit in her box and relax and watch the game. So it's like not putting on the makeup and the gowns and stuff... it was really, I'm at a football game. I'm not at the Met."

What followed her Super Bowl performance was a massive outpouring of love that continued to mount. So much so that three days later, Arista Records, Houston’s label at the time, announced the track would be available for purchase on cassette and VHS with proceeds to be donated to a charity related to the war effort.

"She had the power to connect, and that is what she did that day."

Minor hopes what others take away from both that performance and Houston’s legacy is the power of connection, which he says was on display not only that day, but throughout her entire career.

“There's a lot of people who can sing, but do they have the ability to connect?” he questioned. “Her uncanny ability to take a song and make people believe that she's singing only to them — that can't be taught. You can't learn how to do that. You either have it or you don't."

Minor believes this is what has made Houston's performance stand the test of time, with no artist since then meeting the standard she courageously set with not only her fierce talent, but also her desire to do something different and above all else, connect.

“Where we were in the country, people needed to hear an impassioned cry," he said. "But at the same time, a very passion, powerful, tender thing as well, and it was all the things. It wasn't just, ‘Look at me, look at me, I'm trying to sing the highest notes and I'm gonna belt it out, and I'm gonna show the world that I can sing high’ to the point where you're a screaming animal. She had the power to connect, and that is what she did that day. And we are all better because of it and because she lived.”