Why the Bicycle Is Still the Greatest Adventure Machine on the Planet

Excerpt from Live to Ride: Finding Joy and Meaning on a Bicycle by Peter Flax (Artisan Books)

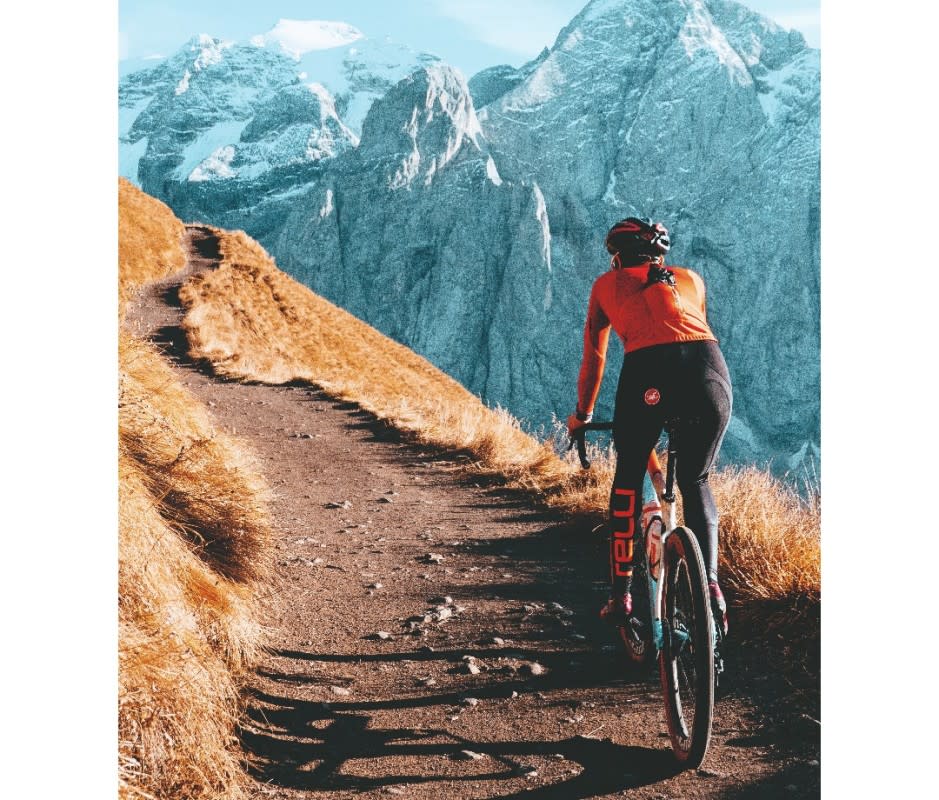

Modern life can be overwhelming. So many of us are consumed with work and family obligations. We are digitally immersed nearly every waking moment. There are video meetings and traffic jams and crowded supermarkets and endless emails. Many of us struggle to take proper vacations or find meditative moments or even unplug for an hour or two a day. And so taking a bike ride in a place where we are surrounded by sky and trees and have the sun on our back is more than training or recreation. It’s healing.

Courtesy image

There is a growing body of scientific research to support this. And again, people who ride don’t need to read the studies to know it’s true. But digging into the science of so-called green exercise is pretty useful if you ever question the value of all those hours spent pedaling your favorite loop. Exercising in a beautiful natural setting has been linked to improved mental health. The greenery along the side of the road and the blue sky overhead and the birdsong and the smell of earth—researchers say that all these things help lower your blood pressure, stabilize the secretion of cortisol, and improve self-esteem. The positive effects can be measured after just a few minutes of exercise in a peaceful outdoor setting, and the impact is greater as you bike farther. People who ride and train for endurance know that it’s considerably more tolerable to go hard and far outside than on an indoor trainer; that’s because riding in a green space is pleasantly distracting and lowers the perceived exertion of such efforts.

Related: This New Annual Pass Can Save You a Bundle on the Best Mountain Biking Trails

But riding isn’t the only way to chase these benefits—you could go hiking or running, for instance—but the bicycle is remarkably well suited to exploring wild places. You go slow enough to hear and smell things yet fast enough to cover a lot of ground. You can coast or soft pedal to recover; you can carry stuff without agony; you can fly downhill. With a moderate amount of training and preparation, you can spend the better part of a day riding through an ever-changing landscape. And even if you don’t want to make that kind of time commitment, you can spend an hour cruising and smell the ocean or circle a lake or watch the sun set over a local park—simultaneously unwinding and exercising without any misery or hard labor.

For people who are serious about training or racing, the bicycle can transform a regular daily ride into an intense nature safari. You get in tune with the topography, the weather—especially the wind—and the sensory experience of being outside. You can bang out so many miles that you feel like a secret traveler, returning at the end of your ride with snippets of rustling cornfields or the late-day perfume of honeysuckle or an hour above the tree line or the theatrics of some nutty squirrel. This is, I think, part of why people love to watch the Tour de France—the spectacle of soaking in the individual moments and the totality of the French landscape. All those sunflower fields and alpine climbs beside tumbling creeks and the way that small towns dissolve into countryside.

Photo: Jered Gruber

Of course, a road bike can at times feel like an imperfect instrument for immersing yourself in nature. A beautiful and quiet paved road can disappear beneath your tires, leaving you open to embrace all the gifts that surround you, but too often there is traffic or development or angry drivers. Most cyclists diligently try to find the prettiest and safest routes in their area, but for a growing number of riders, it has gotten tougher to roll a bike out the front door or out of the garage and find peace.

This discouraging trend informs a number of seismic shifts within bike culture—the popularity of gravel riding, bikepacking, cyclocross, adventure riding, mixed-surface touring, electric mountain biking, and indoor riding. Other than that last trend—the Zwift and SoulCycle phenomena—the rest are all activities and equipment that help people have meaningful outdoor experiences without the chaos of cars or the elbows-out personality of road racing. The purity of the experience can be distilled in a beautiful way.

Related: 7 Wild New Mountain Bike Trails and Destinations

Many of these emerging subcultures highly value self-sufficiency and community. These are styles of riding where your smartphone is not your most important tool. These are communities where sharing an experience with people carries more weight than beating them. Activities in which you still need strength and fitness but are likely more focused on exploration or tenacity than on traditional endurance. You are out in a wild place, in tune with your surroundings, looking to test yourself against natural conditions.

Electric mountain bikes remain a polarizing topic. Some people are worried about trail erosion and resource protection, while others are concerned that relative newbies will get in over their heads in remote places. But in large part that concern is actually driven by ableist prejudice—this idea that only very fit people should get access to ride in certain places. I feel that the positives of electric mountain bikes far outweigh the negatives, that getting exponentially more people to experience the rewards of riding on beautiful trails will mostly just expand and enrich bike culture. This idea that there’s a purity to human-powered riding in the outdoors is pretty dubious if you consider the enormous amount of technology and engineering that has been poured into a modern mountain bike.

Photo: Jered Gruber

Bikepacking—or at least the activity that now falls under that rubric—has been around for decades, but the more recent uptick in popularity is fascinating. I used to backpack and even worked at Backpacker magazine for a number of years, and I think bikepacking delivers all the benefits of that activity (the freedom, the self-sufficiency, the opportunity to really get away) with the ability to go farther and carry stuff with less heartache. It turns out that the bicycle is an amazing tool for going camping in the wilderness.

One thing that all these unpaved riding disciplines and subcultures have in common is an appreciation of the terrain and the surface and all the technical demands that come with that. Nearly all roads in North America have been engineered so a big delivery truck or motor home can safely traverse them, meaning they are easily manageable for a rider with a geared bike and willpower. But on trails, riders must constantly be on the lookout for roots or rocks or changes in the topography or simply the nature of the ground. So people who mountain bike or otherwise ride on dirt or gravel wind up tuned in to the microcosmic world they are pedaling through.

Related: We Tested 9 Highly Rated Exercise Bikes for Your Home. These are the Very Best

But weather impacts everyone who rides. We spend so much of our lives insulated from the elements, sitting in climate controlled offices and parking in indoor garages and getting food deliveries on rainy nights. By contrast, riding a bike in a committed way invariably requires some level of acceptance of temporary discomfort. And for many people who ride, grappling with this minor discomfort becomes quite manageable or even rewarding. Riding a bike means being out in the world, and so coping with a persistent headwind or a summer thunderstorm or a spring ride that has you transitioning from chilly to sweating in two hours can feel empowering. The equipment can handle it, and so can we. There are so many places in North America and Europe where cyclists persevere through pretty rugged winter conditions—New England, the Upper Midwest, the Pacific Northwest, and Scandinavia come to mind. I’ve lived and ridden year-round in Boston and interior Pennsylvania, so I understand how cyclists in areas where winter is no joke tend to keep riding with zeal. They do it because they love to ride and because it makes them feel alive.

The term epic has been beaten to death in the last quarter century, but the spirit that most people intend when they use it is a beautiful thing. Riders want to have intense experiences that test their mettle or connect them to a place or other people. They know they need to get off devices and find something way more organic to engage with. They want something deeper than to be a spectator in a wild natural world—they want to be a participant. They want to feel like an animal, just another physical being finding its way in a beautiful and unforgiving environment.

Photo: Jered Gruber

This is not to say that suffering is an inherent requirement to make that connection. There is a contingent in bike culture that believes that is so, and I think they are mistaken. You do not need to be fast or highly skilled or willing to pedal to exhaustion to feel fully alive. You just need to be out there, turning the pedals, seeking experience and solace.

Can any other machine transport people in so many literal and figurative ways? There’s absolutely nothing wrong with riding indoors—it can be practical and efficient, secure, and even fun—but bikes truly shine when they carry us from home or a parking lot into the natural world, a place where our senses are fully engaged and we feel connected to something larger than our day-to-day existence. In this manner, something that started as a workout or a thrill-seeking adventure becomes something more like restorative downtime, a journey into a wild place that somehow leaves our lives slightly richer than when we set off. People who ride know what I mean.

Related: Hard Lessons Learned From Bikepacking Oregon Timber Trail

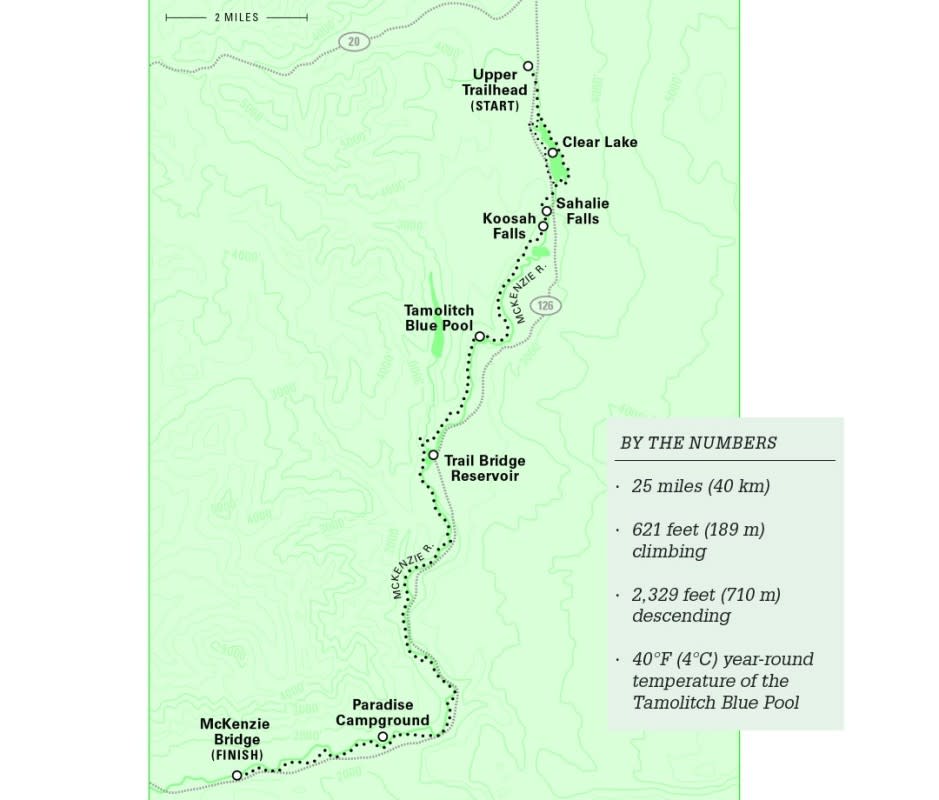

Dream Ride: McKenzie River Trail, Oregon

Throughout his new book, Live to Ride, Peter Flax highlights several "Dream Rides" to harness the unifying power of the bicycle—both with each other and our world. "We all ride for a handful of profoundly beautiful reasons: adventure, access to nature, an avenue of self-expression, the simple joys of speed, and a chance to test ourselves," writes Flax. Here's one of his favorite bucket list rides for engaging with nature.

Located near Bend, Oregon, the 25-mile McKenzie River Trail is a bucket list ride for good reason. The point-to-point route, which has more downhill than uphill, takes riders through an amazing range of natural scenery on the eastern slope of the Cascades. Riders cruise through lava flows and old-growth forest, past raging waterfalls and crystalline blue lakes. Figure on five or six hours for a one-way trip. Several companies offer shuttle service to the trailhead, including Horse Creek Lodge & Outfitters, which throws in a bike wash and a hot outdoor shower when you get back. The ride is well suited to intermediate riders, but it’s manageable for many fit riders if they’re willing to walk a few technical sections. All in all, it’s like a rideable postcard.

Courtesy image

Upper Trailhead

To take advantage of the downward-sloping terrain, most riders start at the northern end of the trail. The early miles take you through the first of several lava fields on the trail.

Clear Lake

Just a few miles into the ride, you’ll cross a charming wood footbridge to reach this strikingly crystal lake—clear enough to see the bottom, which is more than 100 feet (30 m) deep—that’s the McKenzie River’s headwaters. You’ll want to stop for a break, but since the water is a chilly 37°F (3°C) year-round, you might be more inclined to snap photos than to go for a swim. You can ride on the east side of the lake—which is more technical and scenic—or the west side, which is easier and still beautiful.

Waterfall Vistas

Past the southern end of Clear Lake, the route winds along the churning river and then crosses Highway 126 on one of the many charming handmade log bridges on the trail. On the western side of the river, riders will pass overlooks for Sahalie Falls, where water plunges 100 feet (30 m) over a lava dam, and then Koosah Falls, a 70-foot (21 m) cataract with a deep pool at the bottom.

Blue Pool

The river disappears underground for a few miles, and after following a dry creek bed, riders reach the most striking feature on this spectacular route, the Tamolitch Blue Pool, roughly 9 miles (14 km) into the journey. The word tamolitch means “tub” or “bucket” in the Chinook language, and when you see the pool, with steep sides and miraculously topaz water, you’ll understand its name.

Hot Springs

Just a short distance off the trail, Terwilliger Hot Springs has five creekside pools, which range from a mild 85°F (29°C) to a scorching 112°F (44°C). Be forewarned: The scene is clothing optional.

Lush Life

After the Trail Bridge Reservoir, roughly the midpoint of the trail, the route leaves the river and cuts through three-hundred-year-old old-growth conifer forest, a shady playground full of moss and ferns and flowy turns. The trail is mostly smooth and relatively flat from here to the end.

Endgame

You know you’re near the terminus of this beautiful adventure when you pass by the Paradise Campground, one of several Forest Service camping areas with potable water along the route. After that, it’s just 2 miles (3.2 km) to the McKenzie Bridge trailhead and the end of this magical ride.

From the book Live to Ride: Finding Joy and Meaning on a Bicycle by Peter Flax. Copyright ? 2024 by Peter Flax. Reprinted by permission of Artisan, an imprint of Workman Publishing, a division of Hachette Book Group Inc., New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Solve the daily Crossword