Why Homicide: Life On the Street is a criminally overlooked masterpiece

The 1991 book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets begins as every great piece of detective fiction does: with a body. Except the book – written by David Simon, future creator of The Wire – is not a piece of fiction; and its detectives are not the kind from the movies.

Stood around the body of a 26-year-old street dealer, the detectives are flippant and unemotional -– a dead body is just another job to be filed away. They joke about the bullet wound in his head (“You can fix those… they got these home repair kits now”); talk about expired human life in code (“He was ten-seven when we got here”); and pull over to make fun of a cross-dressing prostitute (“Sir, would you have the time?”) before the slog of real detective work begins: admin, phone calls, grand jury summons, unreliable witnesses, punishingly long shifts, and very little sleep.

Working as a journalist with The Baltimore Sun, Simon spent a year with the city’s homicide unit, and immediately deconstructs the myth of the great American detective – a myth largely propagated by film and television. The scene also sets the tone and rhythm for the TV series based on the book, Homicide: Life on the Street, a pioneering police procedural which ran for seven seasons between 1993 and 1999.

Almost a decade before The Wire – itself based on real-life accounts from the same city, same police department, and some of the same people – Homicide: Life on the Street rewrote the rules of police drama. It put characters before the crime and pioneered the idea of the novelistic TV series. A heavyweight detective show which struggled in ratings against lightweight fare such as Home Improvement and Nash Bridges.

Developed by director/producer and Baltimore native Barry Levinson, the book came to Levinson as a potential film project. “It was sent to me,” Levinson said in 2000. “Because almost everything that is written in Baltimore is sent to me.” By then Levinson was an Academy Award winning director (winning in 1988 for Rain Man), but he thought the project would be better served on television, which had the capacity to explore the detectives’ lives over time. He wanted realism: to depict both the reality of Baltimore and the effects of the job.

Levinson brought in Tom Fontana, a writer and producer on the hospital drama St Elsewhere. “I want to do a cop show with no gun battles, with no car chases,” Levinson said. “Well, that’s impossible,” Fontana recalled thinking. “I have to be involved in that.”

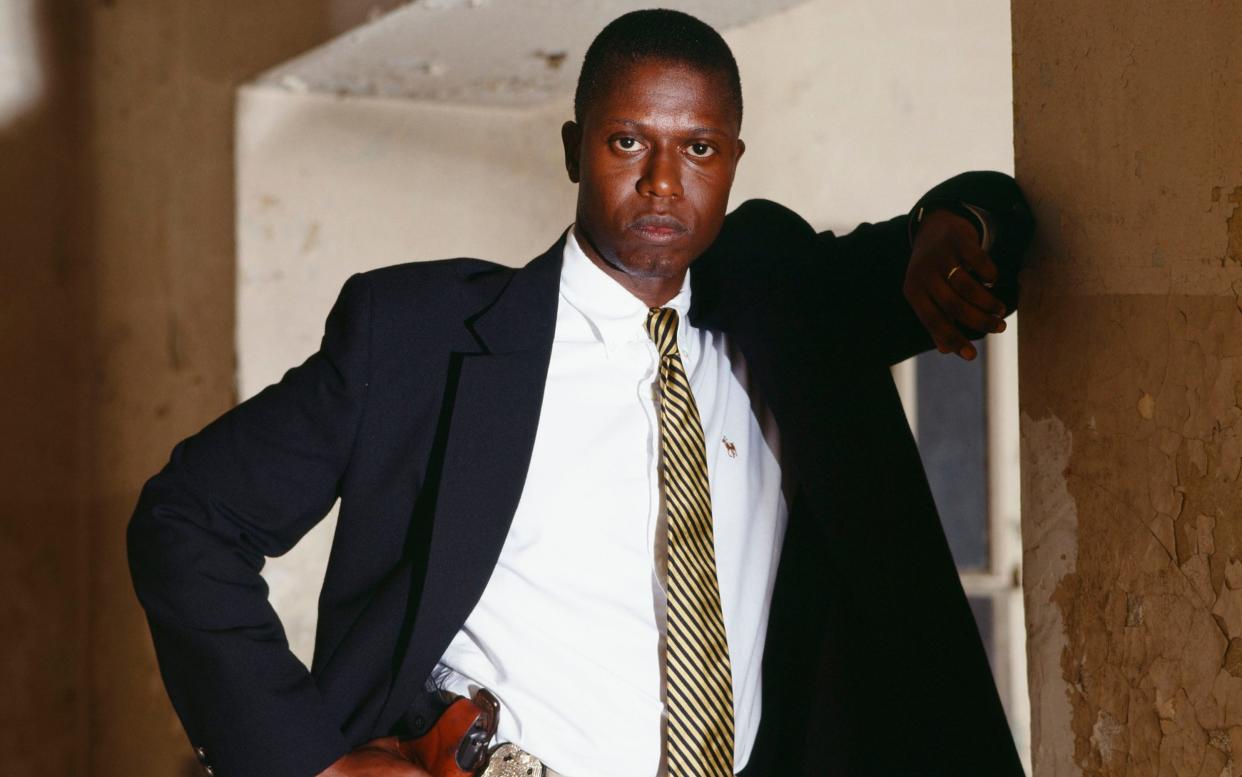

NBC gave Levinson a rare amount of creative control -– including the casting of his ensemble homicide unit. The unofficial star of the series would be Andre Braugher, who has died today aged 61 after a brief illness, as the Detective Frank Pembleton, a powerhouse performance of ego, bluster, and sharp-minded arrogance. Pembleton butts heads with his partner Tim Bayliss, played by Kyle Secor, a fresh faced rookie whose first major case – the rape and murder of 11-year-old Adena Watson – begins a complex, layered relationship between Pembleton and Bayliss that develops over six years.

Former Bond villain Yaphet Kotto would play shift commander Lieutenant Al Giardello, with the rest of the unit played by Daniel Baldwin, Clark Johnson, stand-up comic Richard Belzer, future Oscar-winner Melissa Leo, and veteran actors Ned Beatty and Jon Polito.

Paul Attanasio wrote the pilot script (Attanasio got the “created by” credit on the series) and based the characters on the real-life detectives from David Simon’s book. Some of Baltimore’s finest even signed on as consultants and technical advisors. Gary D’Addario – the real-life lieutenant of whom Yaphet Kotto’s character was based – checked the scripts for accuracy. As recalled in David P. Kalat’s companion book on the series, Richard Belzer – who became a breakout star as Detective John Munch – joked that D’Addario would be “keeping everyone honest.”

Major stories from the series were also based on real crimes. The Adena Watson case, which spans the first season and still haunts Detective Bayliss years later, was based on the sexual assault and murder of 11-year-old Latonya Kim Wallace. Other cases – such as a “Black Widow” who killed multiple husbands for insurance payouts, and an officer shot who was blinded by a bullet to the head – featured in the first season. “I think by the end of the six years we had pretty much sucked every comma and question mark out of that book,” said Fontana on the DVD commentary.

Barry Levinson had an unconventional vision for the series’ aesthetic. Homicide would be shot on 16mm, a cheaper, more mobile camera that allowed the directors to swoop around and circle the actors. “We would let the actors do the scene and the camera would sort of follow and pick up on the action,” recalled Levinson. It was a dynamic working style that took some getting used to for its actors and directors, which included future big names such as Bond director Martin Campbell and Game of Thrones regular Alan Taylor.

Levinson encouraged editor Tony Black to use jarring jump cuts, sometimes repeating lines of dialogue or switching between different takes of the same scene, and the colour of the image was also muted (original plans would have seen the image drained of almost all its colour, so it would have been pretty much black, white, and red). Levinson acknowledged that one of the early criticisms was how “dingy” the show was. “Everybody was used to the vibrancy of Murder, She Wrote,” he said. “So this seemed dark in comparison.”

Homicide: Life on the Street debuted on January 31, 1993, broadcasting immediately after Super Bowl XXVII. It drew an impressive 18.24 million viewers. But after moving to Wednesday nights, ratings dropped for the remainder of the season, struggling against Home Improvement on ABC. Though critically acclaimed from the start, Homicide’s middling ratings began a tricky relationship between the series and network. NBC had been very happy with the pilot and had rushed the series to air, but there was a sense that NBC didn’t entirely understand what Levinson and Fontana were trying to do.

“The network executives were like, ‘Well, is there going to be a murder every week?’” recalled Fontana. “And I was like, ‘Well, yeah – it’s called Homicide!’”

The show was also overshadowed by NYPD, which also debuted in 1993 and was notorious for its edgier content, with ramped up bad language and nudity.

“We never expected Homicide to be a top 10 show,” said Fontana. “It wasn’t designed to be a top 10 show. Our thought was, ‘We’re going to make this really specific show and people who get it, will get it.’ And other people will be watching Nash Bridges or whatever.”

Homicide’s centre point is “the board”, a white board listing all the victims’ names – open cases in red, clearances in black (Levinson recalled that behind-the-scenes, everyone wanted to get their name on the board). Around it, multiple storylines would play out at once, sometimes running across multiple episodes, and in some cases – such as the murder of Adena Watson – are never resolved. For the writers, the characters, not the crimes, were the crux of the show. “It was more about the living than the dead,” said Levinson. Fontana agreed. “The character stuff got to be so much fun to write that the murder always got it the way!” he said.

NBC gave notes asking for fewer stories per episode and rearranged the order of episodes (something it would continue to do in later seasons), causing continuity problems. It was ahead of its time and even watched now (in the right order, I might add) the flow and pace of the first season is difficult to latch onto. But it peaks with the episode ‘Three Men and Adena’, in which Bayliss and Pembleton question their prime suspect in the Adena Watson case during an episode-long interrogation. It’s a searing piece of television drama, with Pembleton and Bayliss attempting to psychologically pummel their suspect into making a confession. In the end, he walks free.

“In terms of detectives and homicide, I think it’s as honest as we can be,” said Levinson about the show. “We allowed all of the human frailties to be part of what makes it so difficult for a homicide squad – because of how affected those guys are by the fact that they’re dealing with people being killed on a day-in, day-out basis… It’s impossible to be perfect with it but I think we’re as accurate as we could be.”

Baltimore police praised the series for its realism and reverence to the job. As remembered in David P. Kalat’s book, the production looked so realistic that one day a criminal tried to give himself up to two actors; people would also walk into the mock-up station to report crimes. Though the show did face some criticism from local cops for a storyline in which a uniform officer kills an unarmed suspect and tries to cover it up – also based on a real-life case from David Simon’s book.

NBC put the series on trial and ordered just four episodes for Season Two. David Simon joined the writing team for the first time (he became a regular fixture later on in the show’s run) and co-wrote standout episode ‘Bob Gun’, guest starring Robin Williams, a pal and collaborator of Levinson’s from Good Morning, Vietnam and Toys.

Williams plays a father whose wife is shot in front of him and his kids while on vacation in Baltimore (look closely and you’ll spot that Williams’ son is played by a very young Jake Gyllenhaal). Williams’ performance ranks alongside his serious dramatic turns in Good Will Hunting and Insomnia. Other future guest stars included Chris Rock, Steve Buscemi, James Earl Jones, Bruce Campbell, Paul Giamatti, Edie Falco, Lily Tomlin, and Jena Malone.

By the third season the show broke some it owns rules. It put bigger emphasis of less realistic “red ball” cases (a term carried over from the book, meaning a high profile, high-pressure crime under media and public scrutiny) – including a three-episode arc about the “white gloves” serial killer and a dramatic shooting of three main characters. Plus, the occasional clichéd outburst of “I’ll give you 48 hours!”

Producers seemed to bow to some pressure from NBC. It feels brighter, with the more chaotic editing toned down. The series also introduced more women – apparently at NBC’s insistence – beginning with Isabella Hoffman as Lt. Megan Russert, the first of several regular cast members to join in subsequent seasons.

Melissa Leo’s existing role as Detective Kay Howard, the lone female detective in the first two seasons, was in fact true-to-life – there was only one woman in the Baltimore homicide unit at the time. The character is also insightful about the reality of her situation. “I’m surrounded by men solving crimes by men against men,” she says in one episode.

The characters even address the changes in a sly opening scene to the third season, bantering about how networks force TV shows to include more sex. “I miss Hawaii Five-O,” says Ned Beatty’s Bolander.

But the third season is arguably Homicide’s finest: still idiosyncratic enough – a storyline about the detectives buying a bar together gets as much airtime as the murders – but with the undeniable pleasure of more formulaic crime drama. And it remains deeply challenging television: Pembleton suffers a crisis of faith; Daniel Baldwin’s detective has marriage break-up; and Crosetti kills himself.

While the fourth season saw Baldwin and Ned Beatty leave the cast, the show pulled in big ratings thanks to crossover episodes with Law & Order. (Years before the Marvel heroes started jumping between each other’s films, Richard Belzer’s Detective John Munch was king of the crossover – he appeared in Law & Order, The X-Files, The Wire, Arrested Development, 30 Rock, and others.) The best episode would see a return to the Adena Watson case as Pembleton and Bayliss find themselves investigating a near-identical murder. Four years later, Bayliss is still tortured by the case, compromising the new investigation and his own mental wellbeing. Even Adena’s mother tells Bayliss: “Why can’t you just let it be?”

The fifth season continued to take dark creative risks. After suffering a stroke, Pembleton deals with the physical and mental effects – including a speech impediment. Producers thought would be a ratings grabber, but hindering the show’s most popular character would have the opposite effect.

By the sixth season – by which point most television series are struggling for fresh ideas – Homicide was still capable of incredible television. In the episode ‘Subway’, Vincent D’Onofrio is pushed in front of a train and crushed almost in half. He’s pinned against the edge of the platform for the entire episode, talking with Pembleton and facing his inevitable death. It’s a powerful, disturbing watch and won the series a Peabody Award. Writer James Yoshimura and D’Onofrio were both nominated for Emmys for the episode, and Andre Braugher won an Emmy for his overall performance that year as Frank Pembleton, and went on to star in top comedy cop caper Brooklyn Nine-Nine from 2013-2021. A seventh and final season broadcast in 1999, followed by a TV movie in 2000.

The show has never been particularly well known in the UK, but you’ve undoubtedly see its influence – not least of all in The Wire. Just as the detective who picks up the call is made the primary investigator on a case, Homicide: Life on the Street feels like the primary of modern crime drama. It’s best summed up by the Adena Watson case: sprawling and epic, with bold creative risks, and finding its drama in a deep bond and conflict between characters. But crucially, there’s no Hollywood-like resolution. The case is never closed.