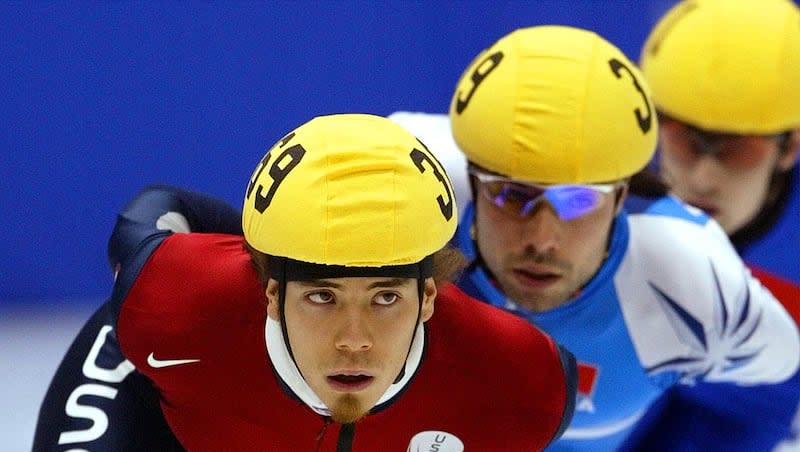

Why Olympian Apolo Ohno’s reinvention includes breaking down stigma of mental illness

Three-time Olympian Apolo Ohno made a deliberate decision that when the 2010 Vancouver Winter Games came to a close, he would retire from short-track speedskating.

He thought he was emotionally prepared to start the next chapter of his life but walking away felt like a divorce, he said.

“I use the word ‘divorce’ because I think there is a lot of similarities psychologically between what happens when your one true love, your purpose, that team, feels like it’s gone, even if it’s by choice, which mine was, by choice,” said Ohno, who had won more medals than any other U.S. winter games athlete to date.

Retiring from the sport that had consumed and defined his youth required that he, then in his 20s, reinvent himself.

Ohno said he had been “incredibly blessed,” by competing in a sport that was his teacher, guide and support system.

“Throughout that process, I, too, have struggled from my own depth of insecurities, self doubts and fears,” he said in an interview earlier this week.

What Apolo Ohno said at national summit

Ohno was in Salt Lake City as the keynote speaker of the concluding event of Stop Stigma Together, a three-day national summit on stigma surrounding mental illness and substance use disorders.

The summit was produced by Stop Stigma Together, a Grand Challenge initiative of the Huntsman Mental Health Institute.

Ramping up to his final Olympics, Ohno said he gave a lot of thought to how he would become a productive member of society doing something other than speed skating, he said.

“How do I do that? You know, what am I good at? Does the universe want me to be here for something other than just going in circles on the ice in Spandex?”

Growing up in sport, Ohno encountered several athletes “who have struggled from depression. We’ve seen athletes take their own lives,” he said.

When he was 10 years old and competing in roller skating, a teammate just a few years older than he was died by suicide. He said he remembers being “extremely confused. I didn’t understand what that meant. I didn’t understand why or how, just complete confusion.”

Years later, one of his roommates holed up in his room for three days. “They just said they’re sick and they’re tired and I was so confused. I was like, ‘How can you be sick for three days? Have you left the room?’ You know, I’ve seen this firsthand, and we’ve had athletes take their own lives here. We’ve seen it happen, you know, and I saw when I was 10 years old,” he said.

He knew how hard it was to perform at an elite level amid personal struggles. But he said he spent his entire career “trying to pretend like I had no vulnerability. I had no cracks in the armor.”

When he was at the peak of his athletic performance, there were few mental health resources for athletes, he said.

“It wasn’t a topic of conversation. Many of us looked down on it because we didn’t understand it. ... It’s like, well, I don’t need to do that. I only use sports psychology to perform in sport. It’s to churn medals not because I need help or because I’m not stable or because I feel depressed,” he said.

The reality is everyone has been touched in some way by mental illness, whether it was a friend or loved one who took their life or struggled with untreated or poorly treated mental health conditions.

“It crosses any socioeconomic class. It has no boundaries,” he said.

Apolo Ohno’s message focuses on breaking down stigma

As he considered his next stage in life, he thought about how he could use his platform to assist in the mental health space.

“I do think that there is there’s a tremendous need not only for voices in this space to come out and say, ‘How do we create better clarity around not only supportive resources that are necessary, but also educating this next generation of youth who will face challenges and situations that perhaps I didn’t grow up with?’ I didn’t grow up with the challenges of being liked on the internet. It wasn’t a part of my childhood,” he said.

Whether he’s speaking to a ballroom of mental health professionals, tweeting messages of support and advocacy or reaching out privately to an athlete struggling with their mental health, Ohno shares messages intended to uplift, inform and break down stigma.

After years of masking his emotions, Ohno said displaying vulnerability remains a work in progress.

“Even when I retired, for many years after, I tried to live my life as if I was in this glass bowl that was perfect. Failure and loss and pain create these realizations that life is not perfect. It’s perfectly imperfect and if you care about what everybody thinks all the time, you actually please no one, and you definitely don’t please yourself. That’s the most important thing,” he said.

Ohno said his well-being hinges on four pillars: how he sleeps, how he eats, how he moves and how he thinks.

“That last one is so critical, and it can paralyze the rest. It’s like a table that doesn’t have one leg. It just can eventually fall down, even if it looks like it’s stabilized,” he said.

Ohno said he feel urgency to break down the stigma surrounding mental illness so people feel comfortable accessing the resources that enable them to be their best selves.

“If we don’t do this now, then what happens? I think that, I think the result of not tackling this is beyond our imagination in terms of devastation. I think that that is a critical piece, and so it should be integrated across every particular age group that we can imagine and it’s going to require a lot of work.”