Why You Should Be Snapping Up Neo-Vintage Watches—and How to Start Collecting Them

Neo-vintage watches are roughly 20 to 40 years old, often way out of style, and typically available for relatively low prices. As straightforward as that may sound, there’s a great deal to understand about neo-vintage watches and why they present one of the most challenging yet rewarding categories from which to collect. As Steve Kivel, third generation N.Y.C.-based watch dealer and head of Grand Central Watch, told Robb Report, “This period of time is really a scholarship treasure hunt, and there is much still to be explored.”

To begin with, there’s a very big difference between a watch that’s 20 years old and one that’s 40 years old. Younger than 20, and a watch is merely pre-owned, such that watches just past the 20-year mark may seem merely older and off-trend (sometimes jarringly so). These younger watches tend to be inexpensive. When approaching the 40-year mark, a watch is maturing into vintage, and its value will usually rise and keep on rising. Watches around 30 years old are less confusing to consider, but it’s important keep the 20- and 40-year boundary effects in mind, as well as the fact that this frame of reference shifts with each passing year.

Kivel states that, “As the more important and exciting vintage watches have been either removed from the collector market to museums or large collections, and with prices dramatically increasing, older and younger collectors have been looking toward the next generation of collectible watches as demand has increased over the last five years. This has led to an interest and understanding that there were many interesting watches [from] the 1980s and ’90s.”

More from Robb Report

F.P. Journe's Final Limited-Edition Watch Is Here, and It's a Stunner

Massena LAB and Raúl Pagès Are Back With a Gorgeous Green 'Absinthe' Dial Watch

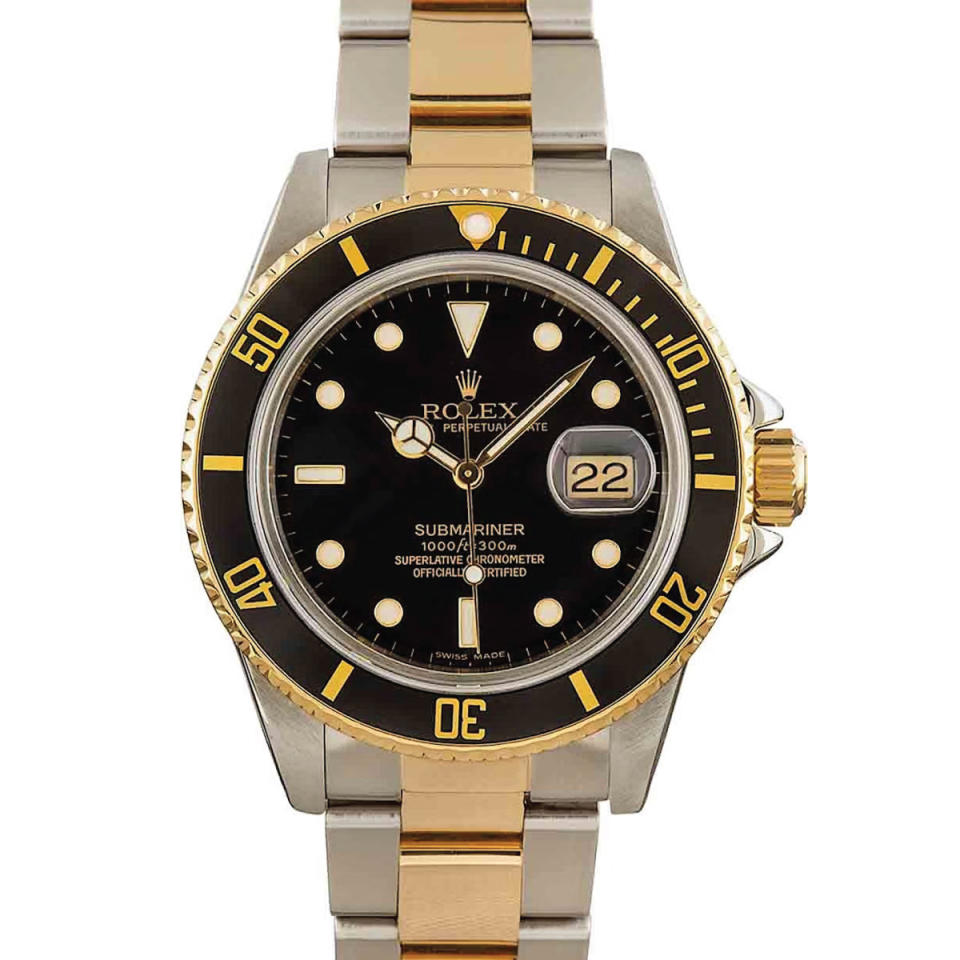

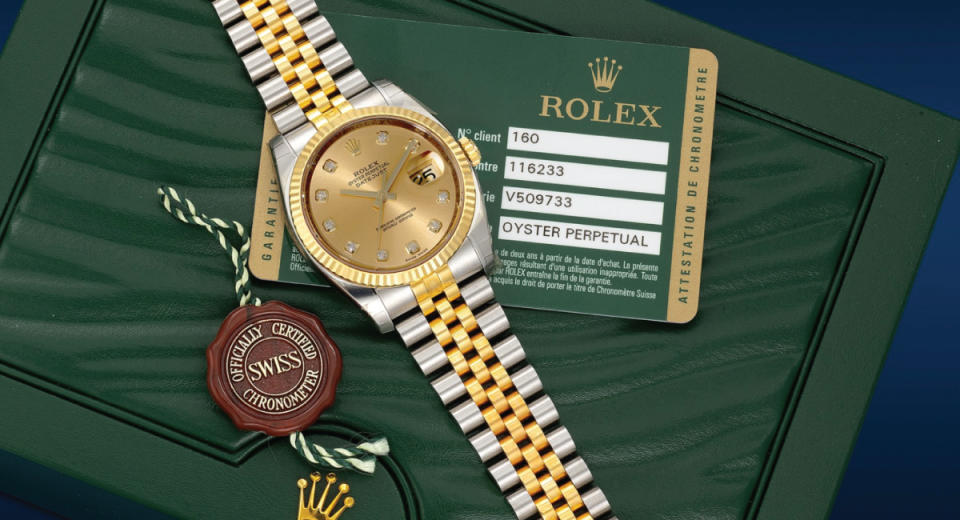

To get a sense of the rising value of neo-vintage watches, consider the Cartier Santos Carree, a quintessential 1980s two-tone watch with a mere 34 mm square case, which, as of this writing, ChronoPulse reports has risen nearly 123 percent in value in the past five years. Yes, Cartier is hot, but so are smaller watches with ’80s style. Also consider the previously out-of-vogue Rolex Explorer II 16570 which ran from 1989 to 2011; ChronoPulse claims it has shot up over 60 percent in the past five years (five-digit Rolex are generally good value these days). Additionally, Rolex 16570s made before 1998 have tritium luminescent paint, which has by now turned creamy vanilla in color, driving up prices for these neo-vintage Rollies. Or consider the Patek Philippe reference 3960, a somewhat stodgily-styled commemorative piece released in 1989: Christie’s sold an example in 2016 for a soft $13,750 and again in 2021 for $27,500—almost exactly twice the price.

A much simpler way to frame up the neo-vintage idea is that these watches are making a 20-year journey from pre-owned to vintage. Semantically, it would have made just as much sense to call these watches “post-pre-owned,” though that’s obviously not a compelling marketing strategy—and marketing has been integral to the emergence of the neo-vintage category.

Dealers quite recently tagged the phrase “neo-vintage” onto watches that used to be simply thought of as older pre-owned models. During the recent watch boom (roughly 2020-2022), many pre-owned and vintage dealers pushed neo-vintage to the countless new collectors burning time and cash while enduring pandemic lockdown. This was a smart move for sellers looking to activate previously stagnant stock. However, it would be unwise to dismiss the neo-vintage category as merely a sly marketing term, because the core assumption underlying the new interest in neo-vintage is solid: The world is full of interesting watches that will become vintage watches before too long.

The question we must ask ourselves as collectors is which watches in that 20- to 40-year range are worth collecting. There are as many ways to think about this as there are collectors, but I believe there are a few core principles that are relevant for all of us.

Listen to Your Gut Taste

Chief among priorities is to make sure you love the watch you’re going to acquire. The reasoning behind this common bit of wisdom usually results in platitudes like “life is short, so love every moment,” but the deeper wisdom resides in trusting what I sometimes call our “gut taste.” By this I mean that gut feeling that a watch looks and feels somehow right to you, even if you can’t quite explain why that is. On a subconscious level, you’re likely on to something. From birth, we are all soaking up the broader culture, and we acquire a sense of what resonates, what seems emblematic of some decade we lived through, or what could become symbolically and aesthetically significant. I believe our gut taste is—in a very real sense—a cultural record written into our neural pathways. You’ve earned it, so use it.

The older you are, the easier it may be to go with your gut taste. I believe this is because (a) as we age, we tend to care less about external validation and can heed our gut feelings with fewer filters, and (b) because we’ve absorbed cultural knowledge that’s roughly the same age as neo-vintage watches. I don’t mean to suggest that someone in their 20s (or even younger) won’t have have killer horological instincts, but having had more time to develop those instincts through lived experience always helps.

Because neo-vintage watches have yet to acquire clear and stable status as must-haves, as rarities, or as valuable timepieces, our gut taste is often all we have to go on. This leaves room for speculation—and let’s absorb both meanings of that word here: the mental act of prediction and the entrepreneurial act of seeking wealth, both of which require us to rely on our gut feelings and take risks.

Nostalgia appears to be a key emotional component here, as renowned watch collector William Massena made clear to me: “I think many of us who started collecting 30 years ago look back at these watches with nostalgia. There are the ones we really wanted but could not afford, the ones that we did not understand then but are now classics, and finally the one which made us fall in love with modern watchmaking.” Massena is pointing to the ways in which culture imprints on us in youth only to emerge as gut taste later in life. If you have even an inkling of horological nostalgia, follow it.

To be clear, I am not only recommending that we follow our gut taste and our nostalgia only for personal or aesthetic reasons, but also to locate watches that will soon go up in value. This is why neo-vintage is so compelling: It challenges us to be the tastemakers who curate the future for ourselves.

Follow the Trends of Rising Value

I normally would not advise following trends, but I believe it’s worth noticing current ones because trends are cyclical. A style that was once a big trend quickly becomes passé, and then it eventually comes back into vogue. The trick is to buy in the dead zone between these trend cycles, when a watch is just not cool at all. It’s a little trickier than it sounds, and, of course, it comes back to following your gut.

A good current example is the small watch craze, which is a return to dressy styles and smaller diameters that went out in the 1990s as big watches came into vogue. But if you want to get way in front of the trend, what about those big 1990s watches? Won’t those soon enough trigger nostalgia and become cool again? Or consider the recent interest in quartz watches, now no longer snootily looked down upon but regarded with nostalgia-laced reverence for that specific moment in history. Or those bizarre reptilian bracelets from TAG Heuer in the 1980s and ’90s that seemed hideous five years ago and are now starting to look, well, at least interesting. That’s a sign.

Another phenomenon worth noting is the re-issuing of a classic design. Think of the Vacheron Constantin 222 that dropped in 2022, a 1970s masterpiece that had gone quiet for decades, or this year’s Piaget Polo, also a thin, gold watch with an integrated bracelet—both indicative of cycling trends. The trick is to get ahead of these revivals if you can, by dipping into neo-vintage, trusting your gut, and homing in on those sleepers. I know it’s possible, because more than a few of my friends started gobbling up 34 mm TAG Heuer Formula 1s from the 1980s two years ago, and now that watch is back and driving up vintage values.

To make these predictions, look back a couple decades or so, and then find those watches that resonate with your gut taste. This is how you become the tastemaker; it’s how you lead rather than follow a trend; it’s how you meet the challenge of neo-vintage and potentially reap its rewards.

Find the Classics

Some watches never became trendy, because they’ve been stable and timeless designs from inception. Nearly the entire Rolex catalog meets this description, and if you are interested in neo-vintage Rolex, you can read in detail about it in our recent article on the topic. Patek Philippe has kept several designs intact for nearly 100 years, such as the Calatrava, and so have Vacheron Constantin, Piaget, and Cartier.

Even more granularly, look for the moments when these brands started to release new versions of historical watches from the early decades of the 20th century, and you’re getting closer to the heat. I own a 1990 Vacheron Constantin Historiques, the brand’s first backward-looking collection that went to market in 1990. My example is from 1990 and based on a watch from the 1930s. These recreations of traditional models can be great neo-vintage finds, pretty much guaranteed to become classics in their own right before long—and they’re on trend as smaller dress watches become popular again.

Whether backward-looking or futuristic, I encourage you to go sniffing around in these traditional brands for models in that 20- to 40-year-old range. I’m confident you can find good value in timeless designs. Wait five, 10, 15 years, and they’ll go up in value and—and perhaps more importantly—horological interest.

Balancing Love and Money

I’ve often said that a focus on value can spoil the collecting experience because it can lead us away from aesthetic concerns toward financial ones. However, I’d be lying if I said I don’t think about making a few bucks (or, more dreamily, many bucks) every time I buy a watch. Experienced collectors know how to bring the monetary and the aesthetic impulses together into a laser-like focus on the watch market. These are the two sides of the brain I like to channel whenever possible.

I’d love to tell you exactly how to gain that laser focus, but I’m afraid only experience and a measure of failure along the watch collecting journey can teach it. That doesn’t mean you should doubt your instincts, but rather that you would do well to follow those instincts, those gut tastes, that cultural record inscribed in your neural pathways in order to gain that next-level experience the most savvy collectors seem to possess. I can’t think of a better category than neo-vintage in which to gain this experience.

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.