Why to Visit Latvia Now

“A ten-minute pause before the main course?” asked our server, Alex. He startled me. I’d never been invited by an American waiter to take more time.

My girlfriend, Jessica, and I were already an hour and a half into dinner at 3 Pavaru, a modern restaurant tucked away in a former military barracks in the Old Town of Riga, the capital of Latvia. Our meal had begun with a half-dozen sauces —including smoked apple, sea buckthorn, and hempseed oil—and flakes of dried honeycomb painted directly onto our place mats and served with bread for dipping, a maneuver that should have felt pretentious, but didn’t. Then came three hillocks of local ostrich tartare, served with a duck egg and lingonberry-beer foam. We had meant to order a bottle of wine from the long, careful list, but Alex kept us busy with a local cider platonically suspended between sweet and dry.

After the pause, we got duck-breast powder and translucent crisps of pig ear over pork belly, pearl barley, and quince sabayon; smoked whole-milk cheese in wild garlic sauce; and feta over black quinoa and japonica quince. And then dessert: black-sesame ice cream, burnt caramel, and a cream of citrus-spiked white chocolate accompanied by a chip of fermented garlic and several sponge cakes that tasted deeply of, well, onion. Improbably, it was magnificent.

“Anna couldn’t sleep for a few nights,” said Alex, pointing to Anna Lo?a, the dessert chef. She waved shyly. “When she finally fell asleep, that’s what she dreamed of.”

By now, despite all the culinary rigor before us, the restaurant had transformed into something like a dinner party in a private home. Alex was trying to open a bottle of cider with a huge chef’s knife. Another server was experimenting with liquid nitrogen, puffs of which periodically blew into the dining room. It was difficult to imagine this happening in New York City, where it would come with an intense amount of forethought and self-consciousness.

It was 11:30 p.m. when Jessica and I finally walked out. “That may have been the most spontaneous and intimate meal of my life,” she said. We also understood why Lo?a might have had trouble falling asleep: there was still light in the sky. In late June in Latvia, the sun goes away for less time than it takes to have dinner.

I wasn’t supposed to be here. As a boy living in Soviet Belarus, little seemed more exotic than Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, the Baltic republics at the western edge of the Soviet empire. Unwilling conscripts into the Soviet system, with northern European rather than Slavic roots, the Baltics always carried a whiff of the West. My family and I went there for vacation and better-made things, like my school uniforms, which were sewn in Lithuania.

I knew that after independence in 1991, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania had lost no time re-modernizing. Only two hours from Helsinki by ferry, Tallinn, the Estonian capital, had even landed on cruise itineraries. But I’d spent enough time in the former U.S.S.R. I wanted to see the rest of the world. Then, in the fall of 2016, I visited Latvia and Estonia on a cultural mission for the U.S. State Department. I’d heard so much about Tallinn that it took me several days to admit that its vaunted medieval center felt like a theme park, with clusters of Finns who’d come to party, swinging steins and bellowing tunelessly outside the bars. Meanwhile, a step outside Old Town brought me into an unreconstructed gray Soviet past.

Riga seemed the opposite: its Old Town was gorgeous and largely unpackaged, with real people living in it, framed by a lovely Art Nouveau central district. If Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, was still refining its style, and Tallinn had rushed and succumbed, Riga was in a sweet spot. Large enough to feel cosmopolitan, but compact enough to be walkable, it had world-class design, food, and lodging at half the cost of Western Europe; an English-speaking population eager to try new things; and a singular combination of outside influences (Nordic, Slavic, Germanic). This charm did not end at the city limits. The size of West Virginia, with a population smaller than Brooklyn’s, Latvia has an exceptionally fertile countryside whose lakes, rivers, and forests have supplied seasonal treasure for centuries: sorrel, chanterelles, cloudberries, zander, roe deer. It’s also where traditional Latvian culture retreated for safekeeping during the Soviet occupation. And Riga is largely without traffic, so you can find yourself flitting past pines and birches in 20 minutes.

Late one night during my 2016 visit, I strolled past the canal that wends between Old Town and the central district. Night kayakers were splitting the water, and despite the October chill, multigenerational gatherings filled the lit-up outdoor cafés lining the banks. Old Town sparkled quietly behind me. A boy was trying very hard on a wooden xylophone, his older brother whispering encouragements from the curb. When I threw a euro into the boy’s hat, he lit up so hard he forgot to keep playing.

Since leaving the Soviet Union for New York in 1988, I’d been looking for a way to reconnect with my past, without success. Belarus remained Soviet in all but name, but I wasn’t Soviet any more. Moscow had become Western in many ways, many less than savory. I’d more or less given up. As I stood in front of that boy, it occurred to me that I was feeling the right angle in Riga: Slavic enough, Western enough, but unglobalized and uncopied. Latvia’s sweet spot was mine, too. I made plans to return, this time with Jessica. I wanted to see what an American would make of it. She’d never been east or north of Berlin.

Maris Laipenieks from California wanted to talk. We were having breakfast in the plush but sleek dining room of the Hotel Bergs, a contemporary property just outside Old Town. Laipenieks’s family had left Latvia in 1942, when he was two, and he was returning after more than 70 years abroad. He had brought his mother’s ashes, his sons, and their sons. Four generations. He was excited, nervous, and slack-jawed. “I can’t believe…” he started saying, and just swept his hand toward the window.

While Jessica heroically busied herself with a massage, I went back to 3 Pavaru to talk to Eriks Dreibants, one of the chefs. “After independence, we were all deep in exotica,” Dreibants said as we shared a plate of pinecone jam, prepared much like any other jam, only with edible pinecones playing the role of fruit. “We had kangaroo tails, antelope. Then we had fusion. Fusion confusion! Ratatouille and shrimp with…Japanese sauce! And then we thought, Enough.” Dreibants and several other chefs composed a manifesto, which said, among other things: “It is time to think about biologically clean products, especially from Latvia.”

3 Pavaru was the flagship incarnation of these ideas. (A sister restaurant exploring them further, Restorans 3, opened in 2015. It offers a more formal though equally delectable tasting menu. An upstairs dining room simulates the sounds and visuals of a forest.) Some of these ideas may seem familiar from the New Nordic craze. But there’s a critical difference in Latvia. No one is looking to conquer the world or become an Instagram star. Shortly before my visit, one of Dreibants’s partners had told an interviewer that he wished the Michelin Guide would stay out of Riga. “This isn’t René Redzepi,” Dreibants explained. “It’s a family business. We won’t go bankrupt because of a bad review, and we’re open to experiment and mistake without our hands shaking.”

“The more you experience what’s out there, the more you realize that the only unique thing you have is your own culture,” Andris Rubins, a managing partner at a prominent advertising agency, told me when we met for coffee and pastries at Café Osiris, an assembly point for Riga’s creative elite. I had asked him to explain the focus on homegrown production at the galleries and boutiques I had been visiting, such as Art Gallery Putti, which focuses on avant-garde jewelry by Latvian designers, and Pienene, which highlights beauty products derived from local flora. “We have lots of history and tradition here,” he said. “But also a clean slate.” He didn’t have to point out how many of Latvia’s neighbors in Western Europe could offer only the former, and how many others in Eastern Europe were as concerned with nationalism as economic innovation. “A friend in London said Riga is London thirty years ago,” Lolita Tomsone, the director of the ?a?is Lipke Memorial museum, told me. (Lipke, a dockworker, became a national hero after he ferried Jews to safety during World War II.) “Not because of the culture, but because of the opportunity.”

It’s an especially promising moment. This year, Latvia will celebrate the centennial of its independence from the Russian Empire, and from June through October Riga will host its first International Biennial of Contemporary Art. When I was there, Jelena Ostapenko had just won the French Open, becoming the first Latvian to capture a Grand Slam. Thousands had watched on an outdoor screen at the foot of the Freedom Monument in central Riga, a 1930s memorial honoring soldiers who died in the war of independence.

The location was not accidental. During the Soviet occupation, the monument was a rallying point. That history lives on. The building that once held the local KGB headquarters, the Corner House, is now a harrowing and moving museum several blocks up Freedom Street. It’s the site of regular tours through interrogation rooms, prison cells, and execution chambers left largely unchanged since Soviet times. Riga remains almost evenly divided between Latvians and ethnic Russians, which makes a visit both surreal and poignant: surreal because Eriks Dreibants is making foam out of lingonberry beer just over there, poignant because the previously occupied are managing to live in peace alongside their former occupiers, with equal pride in their hometown, despite the uncertainty brought on by Russia’s recent efforts to destabilize former Soviet republics.

The young people who fled Latvia during the 1990s are returning to help transform the country with ideas from abroad. Tomsone, the museum director, left in 1999 to pursue Jewish studies in Israel. “I went from a very reserved culture to a very confrontational one,” she said. “But that came with a lot of responsibility for each other, irreverence toward authority.”

We were speaking at Pagalms, a café and bar where twentysomethings were whiling away a sunny afternoon over duck breast and cherry cider. The Latvian aesthetic is so distinctive—something Nordic and lean, something Weimar and lush—that even a board listing bathroom-cleaning times seemed like it belonged in a design boutique.

Tomsone returned to Latvia in 2013. She didn’t have to wait long for a cause. The Ministry of Health was proposing a law that would allow a woman to donate eggs only after having given birth to a child. “So I organized a demonstration,” she said. “I got a hundred phone calls: ‘How could you do that?!’ But we succeeded. The minister of health was fired the following week. Then I got a hundred more phone calls asking: ‘How do I organize a demonstration?’ ”

After our three days in Riga, it was time to make like proper capital dwellers, who often escape the city on the weekends. Before we left, I had coffee with Mike Collier, a British writer and journalist who moved to Latvia 11 years ago and makes his home deep in the countryside. He told me to expect a different kind of serenity. “If the Latvian tourism board could box up peace and quiet, they’d make a fortune,” he said. “You can walk those forests all day without meeting one person.”

The taxi to the Annas Hotel, an hour and a half into the woods in the village of Annas, cost all of $74. Eventually, the butter-smooth highways gave way to gravel. For miles we passed such lovingly tended but modest wooden country homes that when the hotel finally appeared out of nowhere, Jessica and I both laughed in disbelief. An elegant manor, the Annas has landscaped grounds, a spa complex, and a space in the parking lot to accommodate helicopters. We had arrived late, and plates of trout salad and smoked meats and cheese awaited us, accompanied by triangles of dense, sweet focaccia.

The next morning, I went to see Jacob Dimiters, a carpenter and leatherworker who recently organized local artisans into a guild called Northmen. They produce axes forge-welded in the Viking way, bows with horse-tail strings, and watches made with bog-harvested 7,000-year-old oak. (The bogs preserve the oak so well that seeds Dimiters discovered in one hollow sprouted a new tree when exposed to light.) The axes retail for up to $2,000, and the waiting list, primarily from the United States, is four years long.

Dimiters was working as a film editor in Riga when he remembered a childhood wish to build a home from scratch using only hand tools. “When you sit in front of a computer, you can’t touch your work,” he said. “My question was, ‘What can you do with only your hands? How strong were our ancestors?’ Because I think we’re becoming weaker and weaker.” A local carpenter got him started, and his mistakes taught him the rest.

The guild idea came next. On another part of his property, he’s constructing a workshop that will include a public showroom for its wares and philosophy. When I visited, he was preparing to host the guild’s first apprentice class, a 10-day timber-framing and log-building course in the barn of a nearby manor house, complete with three organic meals a day. “We live in a throwaway society,” he said. “The aim is to make things that will outlast us. A carpenter transforms nature into culture.”

Jessica and I had been late checking in to the Annas because we had stopped at Br?veri, near the town of Sigulda, for a pirts, the Latvian version of the steam bath that I’d grown up with in Belarus. I had been going with my father since before I could walk, but in Latvia the experience comes with a dose of the pagan. First, the private sauna attendant, a demonically handsome man with ice-white hair, cerulean eyes, and not one but two chin dimples, plied us with tea from local herbs and honey to open “half the pores.” (“The rest are inside you,” he said.) Then he began to discuss astral fields. A staticky radio behind him was blaring “One Way Ticket” by the 70s disco stars Eruption.

“If the astral field is open…” he began, the blue pools of his eyes gleaming as his face spread into an ambiguous smile.

“How do I open mine?” I asked, a little too eagerly.

“That’s why we’re here today,” he said. He studied me. “Don’t worry, I don’t get a heavy feeling from you.” I brightened, feeling like a psychologist had told me there wasn’t much to discuss. But then he added: “Some people fake it, though.” To the receding strains of ABBA’s “I Have a Dream” and Jessica’s semi-alarmed gaze, I vanished into the sauna.

“We are children of the sun,” he said as he rubbed me with a mixture of honey and salt. I was prostrate on a bed of impossibly fragrant leaves. “Pirts is the world’s oldest solar power. The person who goes once a week doesn’t get sick.” Then he began swatting me with a bouquet of birch, oak, rowan, linden, and hazel leaves. There were various kinds of bouquets, each with a different job. Jessica’s, for instance, had more linden because “God gives woman more energy, and linden brings it down. Otherwise,” he said, quoting a folk saying, “at home it’s a riot instead of peace and quiet.” I had never breathed in such an unadulterated scent of the woods.

The first thing the man saw rising out of my astral field as he swatted me was a rainbow. Then a water demon. Then I was riding a turtle. Things started more ominously for Jessica, whose astral field sent up a clock going backward, then barbed wire. Then, more encouragingly, she walked a tiger on a leash. Afterward, we were gently wheeled around the cool water of a nearby pond and left to lie in the grass of a meadow, the sun shining down softly.

After what could have been 10 minutes or an hour, Jessica sprung from her reverie, stirring me from mine. “This place is so gentle,” she exclaimed, and went back to sleep. I stayed awake, thinking. Since we’d met, I’d wanted so much to share with her something of my past. Finally, I’d found a version of it that had made beauty out of the darkness.

Visit Latvia

Rich in history, with a burgeoning creative scene, the Eastern European nation is only starting to hit the radar of global travelers. The perfect weeklong visit combines four days in the capital, Riga, with three more in the nearby countryside.

Getting There

A variety of European carriers such as KLM and Lufthansa will get you to Riga, Latvia’s capital, via a stop in a major hub.

Lodging

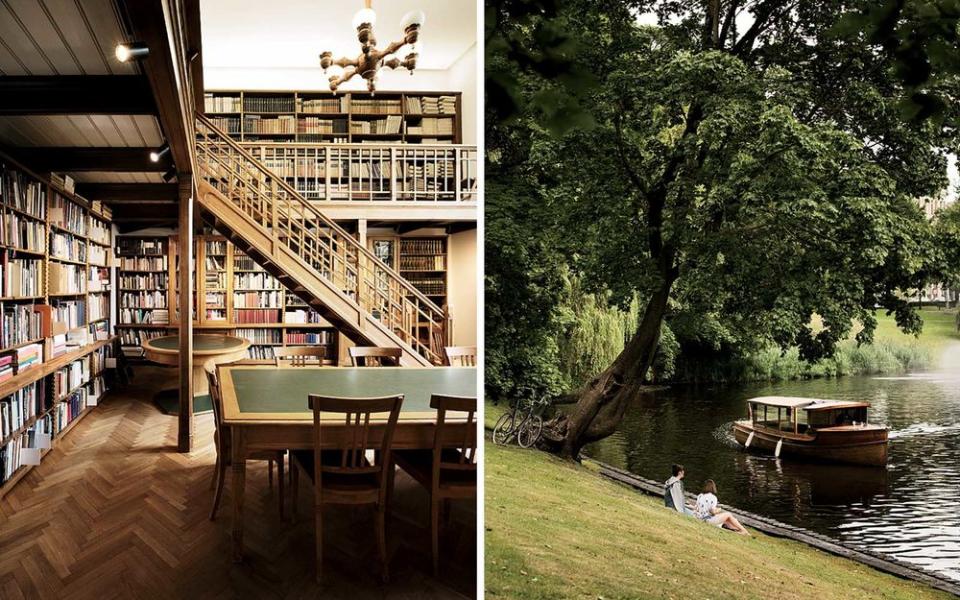

When I visited Riga previously, I stayed at the Neiburgs (doubles from $165), a boutique hotel with rooms overlooking the mansard roofs of Old Town, a library that doubles as a showcase for local textiles, and a spa that can be reserved for private use, as I did every night after a long day of talks. This time, I opted for the contemporary sleekness of the Hotel Bergs (doubles from $250) and the sumptuous old-world style of the Grand Palace Hotel (doubles from $175). With its subdued palette, high-design flourishes, and refined restaurant, the Bergs, which neighbors a luxury-shopping arcade, would not be out of place in Miami. The Grand Palace evokes Vienna: chandeliers, soaring ceilings, and a staff in bow ties. The Annas Hotel (suites from $140), an hour and a half from Riga, offers 10 apartment-like suites.

Eat & Drink

You could visit the Riga Central Market because it’s housed in five of the last eight World War I dirigible hangars on the planet, or because you’ll find the full bounty of Latvian food production, from the countryside to the waters. You will never have strawberries and cherries this sweet anywhere else. Both 3 Pavaru (entrées $22–$34) and Restorans 3 (tasting menus from $49) serve modern Latvian cuisine and should be first on any gourmand’s itinerary, but for an entirely different yet equally heady experience, visit Valtera (entrées $14–$28), which prepares updated versions of traditional food in a rustic setting. We had an excellent dessert of rhubarb purée, hazelnut meringue, rhubarb sorbet, and milk foam.

Experiences

No trip to Riga is complete without seeing the former local KGB headquarters, the Corner House so named because it sits at the intersection of two major streets downtown. Latvians joked grimly that the Corner House was the tallest building in the country — you could see from it all the way to Siberia. The English-language tours are often led by a guide for whom the endeavor is clearly personal.

Riga’s Old Town is a warren of mostly unexpected delights. For shopping, I suggest browsing for avant-garde jewelry at Art Gallery Putti; body-care products derived from Latvian flora (juniper shower gel, milk-thistle eye cream) at Pienene; and household items and accessories — linens, kitchenware, handbags — at Riija.

For a traditional pirts (sauna) experience in the countryside, head to Br?veri (pirts $60 per person), a hotel complex near Sigulda, which is the scenic gateway to Gauja National Park and is about an hour from Riga. Sigulda is surrounded by castles and hiking trails—for locals, it’s the Switzerland of Latvia—and has a small cottage industry of adventure sports (bungee jumping, bobsledding). And while you have to be venturesome to seek out carpenter Jacob Dimiters’s property and the workshop of the Northmen guild of ax- and watchmakers, you won’t regret it. He may reward your effort, as he did ours, with homemade blini with fresh cream and lingonberry preserves or a pizza from his wood-burning oven.