When Women Have Secret Families

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

This spring, I found myself gravitating to TV shows about con artists: Love Fraud, Dirty John, Inventing Anna, and finally The Tinder Swindler, the Netflix documentary about Simon Leviev, who allegedly conned up to $10 million in two years from unsuspecting women he met on Tinder. My novel, about a woman—a mother—secretly married to two men at the same time, would be publishing soon, and watching shows about grifters felt like a comfort ritual, a return to the same search for answers that led me to write the book in the first place.

I can trace my fascination with con artists to 2002, when a baby-faced Leonardo DiCaprio played real-life conman Frank Abagnale in Catch Me If You Can. Abagnale posed as a PanAm airline pilot, deadheading around 250 flights, then forged a Harvard Medical School degree and was hired as an emergency-room supervisor. I was most awed by a scene in the ER when a boy is rushed in after a bike accident, jagged tibia spearing upward from a blood-smeared leg. DiCaprio, as Abagnale, as “Dr. Connors,” tries to conceal his absolute lack of medical knowledge by asking two residents whether they concur with the obvious diagnosis of a broken leg. Then he makes a quick escape to vomit.

I watched the movie multiple times in theaters, and even then I wondered: Why did I keep coming back? Yes I was 17, and yes it was Leonardo DiCaprio, but it was more than that. At that age I was restless, eager for the rest of my life to begin but unsure what shape it would take. I could feel my possible future selves like phantom limbs, vulnerable to every decision I made. Already I mourned the lives I’d never live. Maybe that’s why it felt so exhilarating to watch someone who refused to choose between them, who believed so deeply in what he deserved—in what the world owed him—that he had no qualms about the means of acquisition.

And if perhaps I should have been repulsed by watching someone fool people who are so willing to believe, it also let me feel a tiny bit superior. I’d never buy that act, I thought, even if a niggling voice in the back of my mind whispered: Are you sure?

In The Tinder Swindler, three of Leviev’s victims—women who seem smart, well educated—share how they were conned out of up to $200,000 each. Something about their interviews stood out to me: Despite how their stories ended, they recalled the beginning of their whirlwind romances with smiles and bright eyes, flushed with the kind of “Aren’t I lucky?” glow usually reserved for happy couples describing how they met. As the documentary continues, their smiles turn brittle. The viewer can see them remember, all over again, that the man in those early memories never existed. It’s clear that not only did they lose money, they lost what felt to them like love but was only an illusion.

To me, that was the worst part of Leviev’s con. He left these women to not only mourn a figment of their imagination, but to blame themselves for believing.

I wondered, as I always wonder with these stories, how a person justifies leaving that kind of damage. But as usual, the focus was on the glitz of the trick, not the effort of its creation or the aftermath of its unraveling. Leviev himself was opaque, indecipherable, and yet—we know him, don’t we? He’s a man who feels entitled to taking whatever the hell he wants.

When I was writing my book, More Than You’ll Ever Know, I became interested in a certain type of con artist—someone who, like Leviev, exploits the love of an intimate partner, but without a financial end game; someone who, like Abagnale, refuses to give up one possible life for another. That is: people with secret families. I wanted to know how a person can compartmentalize themselves to such an extreme; how a double life begins and how it’s maintained over years. I wanted to know how this kind of con artist—a grifter of the heart—lives with themselves.

As anybody who’s ever researched people with secret families knows, they are almost exclusively men. Both historically and logistically, it makes sense. Maintaining one secret family requires absence from the other, an excuse to travel often blamed on business. In the early 20th century, only 20 percent of women—including only 5 percent of married women—worked outside the home, and while that number rose to 50 percent (including 40 percent of married women) by 1970, at that point women still needed their husbands’ co-signature to apply for a credit card, obstructing the financial independence a double life requires. And while a man can father multiple sets of children with no one the wiser (just look at Elon Musk), a woman? Not so much. Plus, if she already has kids, she likely bears the brunt of childcare and domestic labor, whether or not she works outside the home—her extended absences would be noticed and discouraged. Let’s face it: everything about a patriarchal society allows cisgender men to keep secrets while binding women to their responsibilities.

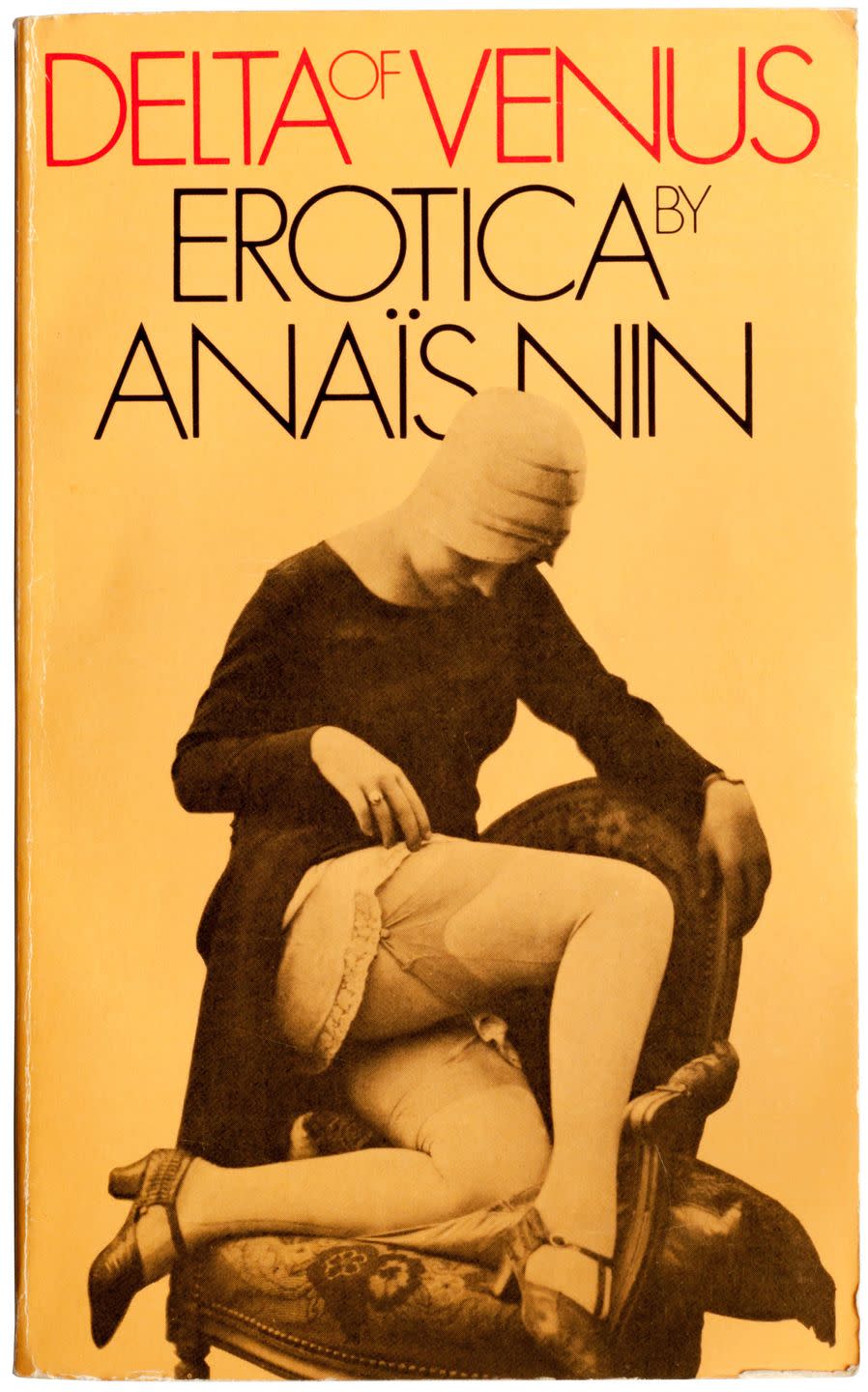

I found one notable exception. The writer Ana?s Nin was born in 1903 in Neuilly, France. Her father left the family when Nin was 10. In 1923, Nin married Hugh P. Guiler in Cuba, and the couple moved to Paris, where Guiler worked at a branch of a New York bank. By 1947, when the sixth published volume of Nin’s diaries, calledTrapeze, begins, she’d had a number of affairs: with Henry Miller and Otto Rank; with a 17-year-old named William Pinckard; even, for a few months in 1933, her own father, with whom she’d reunited.

As for her marriage to Guiler, she is grateful for his loyalty and generosity but not in love with him. Then, in a hotel elevator on their way to the same party, Nin meets Rupert Pole. He is 28, 16 years younger than Nin. Tall and slender, a failed actor and eventual forest ranger, a Superman curl of dark hair falling to his forehead. She writes: “I said to myself, Caution. Danger.” Still, they “plunge deep, deep eyes into each other” as they talk. Later, Pole calls Nin when Guiler is traveling, and she invites him for dinner. They see each other once more before Pole invites Nin on a road trip to California, which she accepts. Pole gives her his ex-wife’s wedding ring to wear so that they can check into hotels without raised eyebrows. At the end of their 18 days together, when she tries to return it, Pole says, “No, keep it. As a remembrance of the trip.”

And so Nin begins the “trapeze,” swinging from California with Pole back to New York with Guiler, inventing stories for each that become so convoluted she has to maintain written records of them in her “lie box.” Finally, in 1955, Nin—who is still, unbeknownst to Pole, married to Guiler—writes that for the last seven years, Pole has been obsessed with marriage:

“I exhausted all the defenses I could invent—that I was neurotic, that I did not want marriage, that I wanted to stay as we were, that I wanted to protect him from a feeling of responsibility…I also felt tired of resisting, feared the effect of my frustrating him, felt also an ironic mockery of the laws, a feeling that if this was going to be a source of irritation and insecurity, oh well, to hell with the laws, I would gamble once more.”

A justice of the peace marries Nin and Pole in Quartzsite, Arizona, a remote rural place whose “ugliness was so extreme it became humorous.” She is moved by Pole’s sincerity, and when she sees a book of criminal records sitting on a telephone table, she smiles. “…The world will put my name down,” she writes, “but I knew that I was making one person happy in the present and that is a great and rare achievement.” And there it was: the double-lifer’s mantra of rationalization.

When I was reading about con artists, romance scammers, and men’s secret families, I wanted to know how one decision built upon another to reach an extreme, unfathomable outcome. I wanted to know the logistics of the deceit and its psychological impact on both the victims and the deceiver. These lines gave me what I was searching for—the insight that perhaps Nin had to believe, in that moment, she was doing a good thing even if it wasn’t the right thing. Perhaps in order to successfully con your most intimate partner, to commit to a double life, you must also con yourself.

Tamar Frankel, author of The Ponzi Scheme Puzzle, writes that all cons have one thing in common: their “inevitable ends.” In 1966, 11 years after marrying Pole and with both husbands claiming her as a dependent on their tax returns, Nin told Pole the truth. He agreed to annul their marriage—and stayed with Nin for the rest of her life, though she also remained married to Guiler. When Nin died in 1977, Pole scattered her ashes above Mermaid Cove in the Pacific Ocean. Nin named him her literary executor, and he fulfilled her wishes by publishing less censored versions of her diaries over the years. When Guiler died in 1985, Pole scattered his ashes, too. Above Mermaid Cove.

After Pole died in 2006, Deidre Bair, author of a biography of Nin, told NPR, “[Pole] didn't feel emotionally swindled. He believed to the very end that the most important aspect of his life was his having been the companion, husband, lover of Ana?s Nin. Ana?s was the love of his life.”

As I researched not just Nin but also Pole—whose ashes are believed to be scattered above the same cove as Nin and Guiler’s—I came across a quote from an interview he gave once to the Telegraph: “I was jealous, yes. But I played the same games as Hugo, pretending to believe her.”

The line surprised me, like stepping accidentally into cold water. Either Pole convinced himself of this over the years, rewriting himself into empowerment—or the only person Nin conned throughout the long course of her double life was herself.

What I’ve learned from my interest in con artists, people with secret families, and in particular from Nin, is that while they inhabit a moral space that is repugnant to most of us, we all have something in common with them. We’re all capable of—and often experts in—compartmentalizing our lives. We reveal different facets of ourselves to different people, our personalities a complex topography impossible to behold all at once. We are all mysterious, at some level, to each other and to ourselves.

As I was writing More Than You’ll Ever Know, imagining my way into a woman who, like Nin, swung back and forth between two lives, there were times I caught myself looking at my husband—edging the grass around the front steps, head nodding to a beat inside wireless headphones; or arms around our children on the couch, two tousled heads of curls leaning on his shoulders—and imagined it the other way: this man I love doing these same intimate, innocuous things 20 or 200 or 2,000 miles away. A thought experiment that, while impossible, still let me feel the impact of such deceit—an earthquake that reduces a home, safe and knowable, to rubble.

You Might Also Like