From Yale to Pole Dancing: The Performing Arts Graduates of 2020, One Year Later

For over a year now, with venues worldwide largely closed due to COVID-19, performers of all kinds have been forced to experiment. A string quartet in Barcelona played for 2,300 potted plants at the Liceu Grande Theatre, while a strip club in Portland experimented with drive-through go-go dancers. Still, unemployment rates for performing artists skyrocketed, jumping from 1.7 percent to 27.4 percent between January and May 2020. Combined with similarly grim employment numbers in the food service and hospitality industries—the eternal side hustles of the creatively inclined—the past year has been incredibly difficult even for established artists, many of whom have had to rely on unemployment insurance or family support.

But what about performers who were just starting out? Even before the pandemic, 2020 graduates of conservatories and performing arts programs faced consistently high rates of unemployment. Throw in the complete dissolution of live performance, and it’s no wonder performing arts grads have had to get creative. Luckily, that’s what they’re best at.

Cami Arboles has been able to carve out a niche even in a harsh economy. A year ago, she was just another unemployed theater studies major with no idea what to do after graduation. By February 2020, she had signed with a New York talent agency. As a student at Yale, she had acted, sang a cappella, and studied opera, so signing with an agency seemed like the first step to realizing her dream of performing on Broadway. “I was literally so ready to move to New York City, and do live theater, and then of course that ceased to exist,” Arboles said.

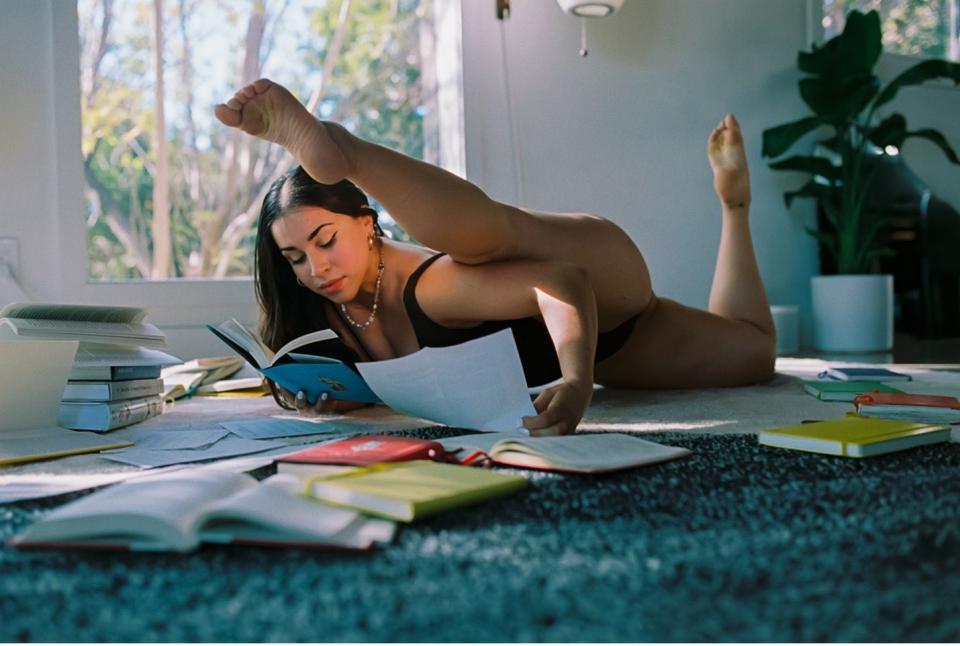

Yale went remote; Arboles went home to Los Angeles, and her senior thesis showcase was cancelled. She went through a period of depression while living in her brother's childhood bedroom “with no employment prospects.” So, to have something to look forward to, she decided to throw herself into an athletic hobby: pole dancing.

Arboles had first set foot—or, rather, hand, body, and lycra two-piece—on a pole in August 2019, as an evolution of her training with the Yale Circus and Aerial Arts Collective. And she was already a certified yoga teacher and an accomplished aerial silks and hoops acrobat. (Full disclosure: I used to go to her campus yoga classes.) “There was a studio in New Haven called PoleFly, and at PoleFly you could train with silks and hoops,” she said. She practiced there regularly, but for a long time, she was too scared to try pole. “I was very insecure in my body, not feeling super comfortable, I was nervous. But I was just like, you only live once, let me just try pole and see what comes with it.”

Two years later, quite a lot has come. A few days after an anticlimactic video graduation, she choreographed a short pole routine in her cap and gown and posted it to Instagram with the caption “48 hours after being conferred my ivy league degree... this one goes out to the class of 2020.” The clip garnered more than 140,000 views and was picked up by a few news sites and meme pages, quickly earning Arboles a hundred-thousand-strong following.

On a pole, Arboles is majestic. In a recent video posted to her Instagram, she twirls elegantly around a pole set up on a Southern California beach. The pole teeters precariously, but Arboles is perfectly balanced as she spins, flexes, hangs upside down, and—here’s the kicker—slides into a perfect split while wearing roller skates. And it’s only, like, the sixth most physically astonishing thing she’s filmed herself doing. She now counts SZA, Vanessa Hudgens, and Kit from The Bachelor among her followers. (She even taught SZA to pole dance for her recent Good Days music video.) And in addition to occasional celebrity clients, Arboles makes her living teaching yoga, movement, and flexibility via video to ordinary people who want to get back in touch with their bodies (like a glitzier version of Yoga with Adriene). Teaching has been one of the most reliable ways performing artists can make money—every single person I spoke to for this article taught, tutored, or coached at some point in the past year.

Arboles has continued to audition via Zoom throughout the past year, but her online classes are what pay the bills. She hasn’t ruled out a return to musical theater once it opens back up. But for now, she’s trying to avoid setting goals or expectations. “You are not missing out on anything that is meant for you,” she told me. Her mantra is “flow, don’t force,” and that attitude has allowed her to easily pivot from live performer to sought-after movement instructor. On her birthday, Arboles shared a screenshot of a text from her mom: “I’m sure you are the only Yale graduate making a living pole dancing.” “Ru proud of me!!!!!!” she asked. “Yes,” her mom replied. Pole might not have been her plan, but it’s far from just a day job.

Other performing arts grads who pursued their dream jobs despite the pandemic found those positions no longer look quite like what they imagined. Henry Shapard, a classmate of Arboles’s at Yale, learned he’d been hired as the principal cellist for the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra within the same hour that he learned school would be remote for the rest of the year. “I will always remember that day as a crazy mix of feeling,” he said.

The early months of 2020 were a whirlwind for Shapard. In addition to flying to Vancouver for his trial, he was also serving as principal cellist for the Rhode Island Philharmonic—and commuting daily between New Haven and Providence, a four-hour round trip. “So, suffice to say, my schoolwork had been slipping a little bit,” he said. For the first month of quarantine, he mostly focused on completing his senior thesis and graduating. Once that was out of the way, Shapard faced another major hurdle: moving to Canada. COVID restrictions have made international travel extremely difficult for Americans, even those with jobs and work permits lined up. When Shapard flew to Vancouver, “there was actually no guarantee that I was going to be let in,” he said. He was approved after a few hours, but that, too, was bittersweet. He hasn’t been able to come home to the U.S. since then because of the border restrictions, and has no idea when he might be able to see his family. “So I've been, you know, on my own up here, basically waiting for the situation to change,” he said.

The nature of Shapard’s work has changed, too. Orchestras can’t perform on Zoom—“the time delay makes it impossible,” he said, but the VSO has been able to play together, albeit without a live audience. The (socially distanced, masked-up) orchestra records videos of their performances, which are then made available to subscribers. The setup has been warmly received, but it’s also prompted some changes. “We play different music than we normally would,” Shapard said. “You can't do the really big symphonies because there’s just not enough people” (due to social distancing requirements).

The distance has also made playing a lonesome experience. “Usually when you're a string player, you share a music stand with one other person,” Shapard said. “Now this year, of course, because of distancing, that's all gone. So for the first time ever I'm playing in a cello section with a stand by myself. And that feels very lonely in a different way, because we get really used to leaning on somebody else, and sharing with somebody else who's right there.”

The uncertainty has been rough on a lot of 2020 conservatory grads. This time last year, Jules Latimer was a fourth-year drama student at Juilliard waiting to find out if she’d been cast in a new series for Paramount+. Latimer didn’t have the most straightforward path through Juilliard. She dropped out after two years at the high-pressure conservatory due to struggles with her mental health, and when she was re-accepted in 2016, she turned to crowdfunding to help pay her tuition.

But by March 2020, Latimer was in a great place: she had a manager, had just done a play Off-Broadway, and was in the last stages of auditioning for a major role in the streaming series. But when Broadway went dark and Juilliard went remote, things got scary. The last straw was when a man attacked her, yelling about COVID, as Latimer picked up her stuff from Lincoln Center. Latimer and her girlfriend packed up—the apartment smelled like bleach, Latimer remembers, because they were cleaning so obsessively—and went to stay with Latimer’s mom in Atlanta.

A few days turned into a few weeks, then a month. The casting process at Paramount+ kept getting delayed. Eventually, though, she got the call: she’d booked the job. The shoot was set for November, in Los Angeles. But the delays from Paramount kept coming. COVID had created many roadblocks for the industry, and the project’s lead dropped out. The shoot moved from November to February; from California to Calgary. Latimer picked up side hustles, including a stint registering voters through a nonprofit during the 2020 election. Unemployment insurance helped. So did previous years of frugal living. “We're so lucky because I lived in a hole in the wall in Brooklyn… that room was like 525 a month. I was living so cheap. I actually collected a lot of my checks and saved all my money from that year. So we were sort of living off of that,” Latimer said.

Filming finally started in Canada in February, and Latimer is thrilled to be working. “It’s a dream. I mean,” she laughed, “it’s kind of a weird nightmare dream with COVID.” Despite all the setbacks, and the distance from her partner and family, she feels “incredibly fortunate” just to be able to work in her chosen field.

Her Juilliard classmate Emma Pfitzer Price has taken a slightly different route. When she moved from Kentucky to New York to attend the conservatory, Price was committed to doing live theater. By March 2020, she had found a manager through the type of live show that is more or less impossible to put on during COVID: “We were all playing like six different characters and had insane wigs and hair and makeup, and we were touching each other and kissing each other and fighting and rolling on the ground and pretending to be on fire,” she said. “And it was this really full body experience.”

Once the pandemic extinguished the entire live performance scene, Price had to change her plans. She started self-taping auditions, relying on unemployment insurance when her babysitting gigs didn’t cover the bills. She booked a role on a TV show, but by the end of the summer she realized she needed a consistent income. Price hoped the stable financial situation that comes with a day job would let her “come to my acting work with a lot more joy, and a lot more presence.” Restaurant work no longer seemed like a good option. So she started working as a teacher at a Montessori school in South Harlem.

For Price, teaching has been a great day job that allows her to continue auditioning. But teaching has also kept her creatively motivated as a performer in a year without theater. “What I need right now is just that reminder of what is the root of all of this for me, and it's that sense of play,” she said. “And that started when I was a kid, and I was playing imaginary games in my backyard with my young friends. And I see that same impulse and all of these kids I work with.”

It’s difficult to overstate the devastating impact the pandemic has had on the people who make the arts possible. Aspiring performers without family or institutional support have had an especially tough time, and these four stories from graduates of prestigious schools shouldn’t be taken as the default narrative. Still, it’s exciting to see how talented performers have managed to thrive, to pivot, or to simply make ends meet. Hopefully, live performance will safely return soon—vaccination rates are climbing, and theaters are cautiously reopening. For now, performers everywhere are waiting in the wings.

You Might Also Like