Yes, It's Possible to See Rare Snow Leopards in India’s Himalayan Mountains — Here’s What It Was Like Tracking the 'Gray Ghost'

One travel writer sets out on the trail of these elusive big cats, and reports on the delicate truce between them and their human neighbors.

Himanshu Lakhwani

A female snow leopard with her cubs near the village of Ulley, in Ladakh, India."Get in the car, quick,” shouted our guide, Tchewang Norbu, just as his crew had begun setting up a tailgate picnic. He came running down the hillside, a cloud of dust in his wake, and in less than a minute our equipment was loaded, hot tea reluctantly wasted, car doors slammed. And then we were hurtling downhill at breakneck speed.

That the road, or what passes for it, bordered a sheer cliff seemed immaterial. “Slow down,” Norbu said to the driver as we approached a bend, beyond which the road disappeared. “Stop!” Jumping out, he ran forward and trained his binoculars on a distant ridge. When he turned back to our vehicle, his face was wearing a wide grin.

For nearly a week, we’d been tracking the snow leopard in and around the village of Ulley, in western Ladakh, India’s northernmost province — one of very few accessible regions where visitors stand a decent chance of spotting this elusive and endangered big cat. We’d trekked up slopes of loose shale following footprints, crouched in wait along grassy ridges, and braved winds that seemed considerably colder than the “feels like” reading on our weather apps. We had seen two varieties of wild sheep, ibex, Himalayan wolves, multiple bird species, and a lone red fox. But the snow leopard, known in the region as the “gray ghost,” had eluded us. Until now.

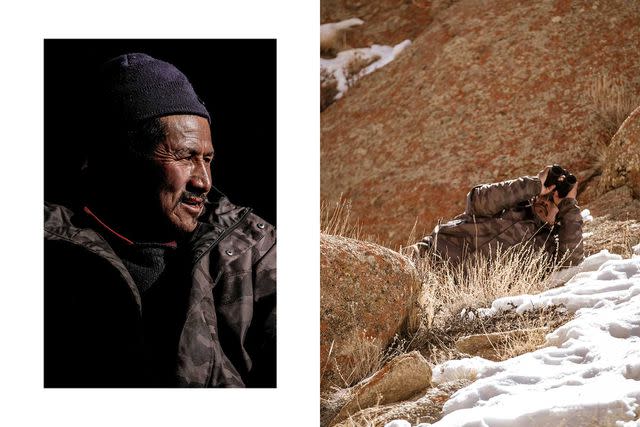

Himanshu Lakhwani

From left: Tchewang Norbu takes visitors on leopard-tracking expeditions in the Himalayas; Norbu scans the mountainside for signs of leopard activity.“Look over there,” Norbu said, pointing to the top of a hill nearly half a mile away. “I don’t see anything,” I replied. As if in response, a snow leopard revealed herself, stretching in the classic “cat” yoga pose, shaking off the dust and cold of the night and basking in the warmth of the morning sun. Even at a distance I could tell she was a beauty. Her coat, which she was giving a good lick, was a grayish beige, her rosette markings dark against the pale background. Her tail, which she flicked every now and then, was long and thick.

With her were three cubs, one of which was attempting to play with its siblings; they refused to stir. The mother lowered her head, allowing her baby to climb onto her back, then fall off. Suddenly she stopped, sat up, and looked straight in our direction. Word of the sighting had spread, and eager safari-goers and other residents of the Snow Leopard Lodge, the homestay Norbu owns, had arrived, leaving a cloud of dust behind them that could be seen for miles around. (February is right in the middle of peak tourist season, so company was to be expected, though in this remote region, it rarely feels like a crowd.)

Nonetheless, all this human activity seemed to have caught the mother’s attention. We were told to quiet down, lest she decide to leave. Sitting on her haunches, she watched us. The “feels like -10 degrees Celsius” wind found its way through my thermals as a flock of chukar partridges fluttered in a tree below. The wild sheep on the hillside above grazed unperturbed. Finally, Lady Leopard decided we posed no danger after all, and lay down for a snooze. We heaved a collective sigh of relief.

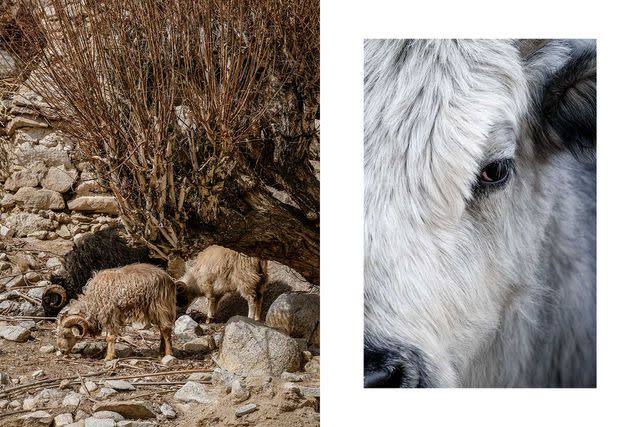

Himanshu Lakhwani

Himalayan wildlife around Ladakh’s Snow Leopard Lodge include mountain goats and yaks.“I told you that you wouldn’t leave without seeing the shan,” Norbu said with a smile, using the Ladakhi word for snow leopard. I smiled back. Western Ladakh is mostly barren, its mountains stark and shale-covered. Spotting a snow leopard, or any animal for that matter, is like finding the proverbial needle in a haystack. But Norbu, who has been guiding visitors since 2004, is something of a legend when it comes to tracking these creatures. He is a favorite of photographers, documentary filmmakers, and conservationists. “To me the shan is like the Dalai Lama of wildlife,” he declared one day as we camped in the backyard of the Snow Leopard Lodge, scanning the neighboring hill for signs of the animal. “It’s the most powerful creature here. Don’t we always look up to the powerful?”

The relationship between man and apex predator hasn’t always been this respectful. Norbu explained that, as a child, he learned to track snow leopards from his grandfather and father, both formidable hunters who would seek revenge when the cats killed their cattle. (Historically, snow leopards were also killed for their pelts and body parts, which were used in traditional medicine.)

In Ladakh, conservation of the species got a boost in 2002, when the Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust (SLC-IT), a much-lauded agency that works in the Himalayan regions of Ladakh and Spiti, introduced homestays in areas where human-animal conflict was a persistent problem. “The homestays are the single most important contribution to conservation,” said Dr. Tsewang Namgail, director of the SLC-IT. “Until they arrived, trekkers and safari-goers would mostly camp outdoors. Often, they would leave garbage behind. Locals suggested that if visitors stayed with them it could generate revenue and reduce stress on the environment.”

Himanshu Lakhwani

Traditional Ladahki décor in the living area of Snow Leopard Lodge.In those days, very few tourist dollars were finding their way back into the economy. The SLC-IT helped villagers set up more than 200 homestays, including the Snow Leopard Lodge, across the western part of Ladakh and has trained residents to become trekking guides and naturalists. Norbu runs the lodge with his family and other villagers. So, while the facilities are simple — old-school wood-fired heaters in all the rooms and hot water that’s fetched in buckets — the service is heartfelt. It’s also easily the best the region has to offer.

In addition to the homestays, Namgail tells me, village cafés that sell handmade souvenirs, as well as a livestock insurance program that covers predator attacks (both are promoted by the SLC-IT, but run by villagers themselves) have helped reduce human-animal conflict even more. “Since the homestays started, revenge killings have completely stopped. People realized that there’s more money to be made by protecting the shan,” Norbu said. Estimates suggest there are between 400 and 700 snow leopards living across the Himalayas, though Namgail said camera traps suggest a much higher number.

Himanshu Lakhwani

From left: Visitors track wolves in the snow outside the village of Ulley; a magpie near Snow Leopard Lodge.On my final day in Ulley, I spent more than four hours watching the mother and her cubs sleep, play, and groom each other. I learned snow-leopard trivia from Norbu: how, when they kill a large animal like a sheep, they will feed on it for a week, starting from the outer limbs and working their way to the inner organs, which slows down the decay of the carcass and avoids attracting scavengers.

As the sun dipped behind the mountains, Norbu reminded me it was time to leave. It was a two-hour drive to the capital city, Leh, and I had a plane to catch. I was tempted to spend more time there, to make the most of this rare experience. But when I peered through the scope to see what the playful cub was up to, it wasn’t there. Neither was the mother. For now, at least, the ghosts had slipped away.

andBeyond offers leopard-tracking Ladakh itineraries that include accommodation at Snow Leopard Lodge.

A version of this story first appeared in the December 2022/January 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Mountain Spirits."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.