Ziggy Marley on Bob: ‘People love my father – but he had violent tendencies, he was a fighter’

It was 8.30 pm on December 3 1976 in uptown Kingston, Jam-aica. Bob Marley and the Wailers were rehearsing in the large house at 56 Hope Road that the singer had been given by Chris Black-well, the boss of Island Rec-ords. “I remember telling my mother, ‘I want to come, too’,” says Ziggy Marley, Bob and Rita Marley’s eldest son, who was eight at the time and -staying at his great-aunt’s house. “And she was like, ‘No, you have school tomorrow’.”

In 1976, the Caribbean nation was in meltdown. Gang warfare linked to rival political factions had erupted on the streets of the capital: there had been so many murders that a state of emergency had been in place since June. When Rita left Hope Road later that night in her VW Beetle, the guard post was mysteriously deserted as two white cars sped into the compound, -bullets flying from their open windows; one grazed her skull, leaving her covered in blood as the gunmen entered the house, searching for the reggae superstar. Marley himself survived a shot to the chest that left a bullet lodged in his arm; -others, including his manager, Don Taylor, received torso wounds.

Ziggy was asleep when, in the middle of the night, “There was a knock at the door – ‘Wake up! Wake up! Wake up!’ The police come and grab me, my brother and my sisters, put us in a car and we sped away up to Strawberry Hill, where my father was,” he says, referring to the house up in the Blue Mountains owned by Blackwell. “My mother was still in hospital, but the day after, she came – I remember her in a robe with her head wrapped up.”

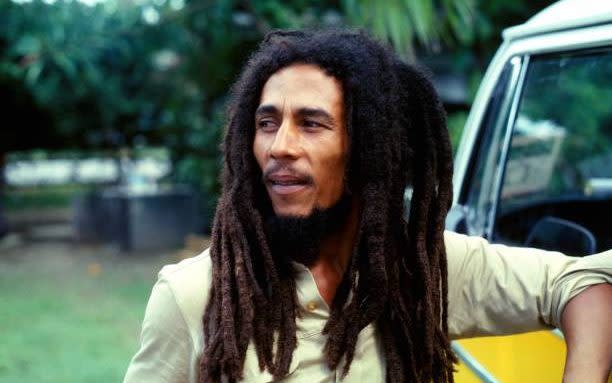

We’re in a hotel by the Thames, talking about this dramatic assass-in-ation attempt, a reconstruction of which opens the new film Bob Mar-ley: One Love – co-produced by the eight-time Grammy winner, who’s sitting opposite me in a faded green combat jacket and beanie. His dreadlocks are shorter, but in voice, looks and man-ner, he’s the image of his father. “This was the life--changing moment for him,” Ziggy says. It was also a way to avoid all the biopic -clichés.

“We didn’t want to make a movie from Bob’s birth to Bob’s death. This period has action and adventure, bullets flying, a love story, tragedy, -emotion, and for me it was a very -significant time in his life, when he really had to question himself and come to some kind of understanding of his purpose.”

The identity of Marley’s shooter remains murky, although the attack has been linked to Jim Brown, a -gangland enforcer who soon after became a powerful drug lord in the US cocaine trade, before he was burnt to death in a Kingston prison cell in 1992. A friend of -Marley later claimed that the singer, on subsequently meeting Brown, recognised him as one of the men who came to the house that night. “Eventually, he knew who did it and, you know, everybody kind of figured out who did it. It was no secret after a while,” Ziggy tells me. “But we have a code, you know. It’s not necessary to say who did it. That’s our code, it was Bob’s code and we just keep it.”

That sense of Marley as the product of Trench Town, where he rubbed shoulders with feared gangsters such as Bucky Marshall, is key to the man behind the inspirational global icon. “He was a street guy, and he knew the street guys,” Ziggy says. “They grew up together… Plenty of people love my father, but my father was… him rough, he had violent tendencies, you don’t f--- around with him, he was a fighter.” Besides, he insists, quoting Marley’s 1978 song Time Will Tell, which he recorded in the UK after the shooting, it’s “not the brothers / But the ones who sets them up”.

Therein hangs a tale. On that fateful December night, Marley had been rehearsing for Smile Jamaica, a concert organised by the ministry of culture purportedly to defuse the simmering tension, and held two days later in Kingston’s National Heroes Park. Marley’s participation, Ziggy explains, was taken as an endorsement of the socialist -government of Michael Manley, who would capitalise on it by calling an election shortly after the concert. The citywide violence was happening between gangs that had the tacit support of Manley’s PNP (People’s National Party) and those backed by the conservative JLP (Jamaica Labour Party) of Edward Seaga. A neighbour of Marley reported hearing Alvin Patterson, the Wailers’ percussionist, say that it was “Seaga men” who “come fi kill Bob”.

It’s highly likely that there was another bad actor in the piece. Manley had expressed support for Fidel Castro and the last thing America wanted was another Cuba on its doorstep. “I wanted to explore the CIA’s part in the political turmoil in Jamaica,” Ziggy says. “My father, who was a big influence and seen to support Michael Manley, was an issue for the American government, because they did not want Jamaica to become Communist or to become allies of Russia. I feel like the assassination attempt was a part of that proxy war that he got mixed up in, because of his influence in Jamaica.”

So, does he blame Seaga or more specifically the CIA? “Well...,” he pauses, “it’s a combination. I would say ‘the system’, which is not one [political] side or the other; both sides try to use you. One side sees how useful you are and tries to paint you in one way to gain influence, and the other side sees you as having too much influence. It’s Seaga, and it’s both of them, it’s all of them. Nobody’s hands are clean.”

It’s a dark and complex subject, but One Love finds much light alongside it. The British actor -Kingsley Ben-Adir inhabits Marley with deep humanity and studied ease; Bond girl Lashana Lynch fires up Rita Marley into the sunny, ardent source of strength she is in real life; while James Norton gives a breezy confidence to Chris Blackwell.

The film is directed by the American Reinaldo Marcus Green, fresh from his Oscar-nominated biopic King Richard, about the father of the tennis superstars Venus and Serena Williams. The production’s mix of nationalities, though, was a concern when it came to capturing the very particular feel of Jamaica in the 1970s. “There was anxiety, of course,” Ziggy says. “But – and it might seem dismissive of reality, or maybe I smoked too much herb – the decisions I make are guided, and things always work out the right way.”

After Ben-Adir was cast as his father, Ziggy says, “I was never worried, even when it was hard for him. And it was hard. There was tension with him and the director and writers, because they’re not Jamaican; they have no idea how our culture is, the Americans. They’re professionals, I wanted to let them do their thing, but I knew that me and maybe somebody had to come in and make sure the dialogue was right, and the reaction to situations was authentic to Jamaican culture. Kingsley didn’t know that, though. He was like: ‘It’s not real, it doesn’t sound like Bob, it doesn’t feel like Bob.’ I wasn’t worried, I knew we were going to fix it. But sometimes, you know, heads bumped because of how heavily we took this: in the early days, until it smoothed out, it was rough seas, rough seas.”

The cultural divide extended to the scenes of Marley and the Wailers playing football in Battersea Park during his exile in London after the shooting, when he was writing and recording the 1977 album Exodus. “I remember telling them, if you don’t get the football right, it’s not a Bob Marley movie,” says Ziggy, laughing. “Because Bob loved football. He would be more upset about that than anything else, if the football wasn’t done right.” The scenes are lovingly recreated from photographs of the time. It’s perfect.

For a time, Marley attributed a dark spot that had appeared under his toenail to a footballing injury. In fact, it was a rare and aggressive form of skin cancer that would ultimately lead to -his death in 1981.

In the film, Blackwell is seen urging Marley to see a doctor, yet there are subtle hints there, Ziggy says, that not enough was done to save his father’s life. Blackwell was certainly instrumental in lifting Marley out of a local music industry in which artists could have number one records, as the early Wailers did with their debut single, Simmer Down, in 1964, yet still earn a pittance. Blackwell gave Marley an international platform, and paid him proper royalties.

“Chris was a two-edged sword,” Ziggy says now. “In the scene when Bob’s talking about cancer, Chris is like, ‘You need to see a doctor... and maybe if it work out, we can make the tour.’” It clearly remains a source of personal frustration that “when my father was sick, there were people around him who just wanted him to keep going… there was that element of: let’s get the business done”. Ziggy believes that a relatively “mediocre effort” was made to prioritise Marley’s recovery. “It wasn’t like, ‘We’re cancelling the tour, no matter what Bob says.’ I mean, Bob was stubborn also, but the effort wasn’t maximum enough.”

I want to ask him about Marley’s relationship with his own white heritage. His father was a plantation overseer, originally from Crowborough, East Sussex, who deserted Marley’s black teenage mother, Cedella. Growing up mixed race was difficult in the rural community of Nine Mile, in the north of Jamaica, where the youngster was made to feel an outsider and called names relating to his light skin tone. “I think Bob wanted to be more black than he was, even in his skin colour,” Ziggy says, touching his arm. It was something that would torment Marley when his Rastafarianism and Afrocentrism took him to Africa, he says. “The fact that his father was a white man and that a white man [Pieter Botha] had apartheid in South Africa, it must have tore him apart that that was a part of his heritage.” Ziggy himself feels “no connection” to that part of his ancestry, he says.

Last month, there was a stir when the Duke and Duchess of Sussex visited Jamaica for the world premiere of One Love, posing with Jamaica’s prime minister, Andrew Holness, and declaring themselves fans of Marley’s music. The island nation att-ained independence in 1962, yet remained in the Commonwealth. Holness wants to make it a republic, breaking its historic link with the Brit-ish monarchy.

In recent years, there have also been repeated calls for Britain to pay reparations for the wealth it owes to its part in the -transatlantic slave trade and the use of slave labour in the former British colony. The former is Ziggy’s primary concern. “I feel like we don’t have to depend on somebody else to give us something; we need to stand up on our own two feet,” he says. As for the governor-general? “That’s from back in the colonial days. In our eyes, we don’t need that any more. So I feel like the first step is not to ask for reparation, the first step is to ask for true freedom, true independence.”

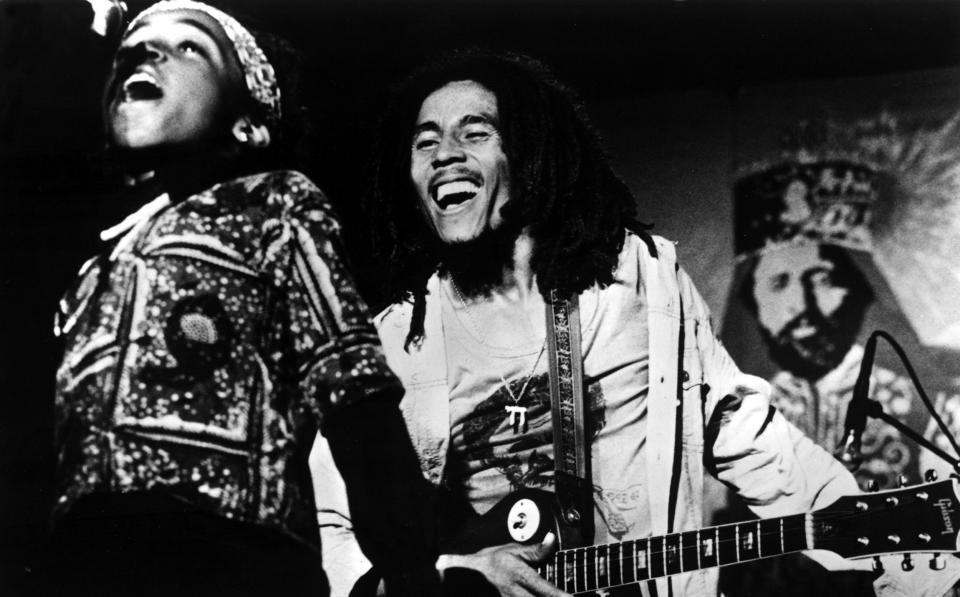

In some ways, his father has become almost a universal symbol of peace and love, yet Ziggy is conscious that that’s only part of his story. “Bob had many sides,” he says, “and I think the peace side is much more easily marketed than his revolutionary side.” In the film, Ben-Adir sings Marley’s War, from his 1976 album Rastaman Vibration:

Until the philosophy which hold one race

Superior and another inferior

Is finally

And permanently

Discredited

And abandoned

Everywhere is war

Me say war

“I think most of him was this peaceful, loving guy,” Ziggy stresses, but the other side is sometimes forgotten. As for the well-publicised multiple relationships that resulted in children after the three Marley had with Rita, he says, “It is what it is. I didn’t see my mother telling us, your father is doing something wrong. My mother wasn’t a vindictive person, and my father wasn’t a person that hides it, like, ‘Let me sneak around here and do this.’ It’s life.”

Of course, whatever one says about Marley the man, his music remains transcendent, and it was part of Ziggy’s life with his father from the start. “The musical connection with him and us is a family thing. If he was writing a song, he’d call us to come and sing.” He laughs. “If we were running around, making noise, he’d shout, ‘Come!’, like ‘You’re disturbing me, you better come and sing’, you know.”

The film includes a resonant flashback of the young Wailers arriving at the studio of a gun--toting Coxsone Dodd in Kingston, with the innovative, eccentric Lee “Scratch” Perry behind the controls. “Scratch was such a...” Ziggy begins, and a smile steals over his features as he remembers being taken to see the dub producer as a child. “He wasn’t like any of the other guys. He was like a magician, even a wizard kind of guy.”

Ziggy would go on to find success as a musical artist in his own right, bringing a sweet soul to the album Dragonfly in 2003, and returning to his reggae roots in Rebellion Rises in 2018. His father wrote the first song released by Ziggy and his siblings Sharon, Cedella and Stephen, as the Melody Makers, and had Ziggy and his brother join him on stage at the One Love peace concert in Jamaica in 1978 that is at the heart of the film.

By then, Marley had already been diagnosed with the cancer that would lead to his death three years later. Ziggy remembers visiting him in hospital in Miami close to the end. “He was in an intensive-care unit and I was like peeping up to the door like this, trying to see him, you know.” He’s back there, with his father waving him to come close. “His last words to me,” he tells me, “were, ‘On your way up, take me up. On your way down, don’t let me down.’”

Bob Marley: One Love is in cinemas from Wednesday