The Art of 'Alien': How H.R. Giger Created Modern Cinema's Most Iconic Movie Monster

The summer movie season is about to get considerably more horrifying with this Friday’s release of Alien: Covenant. A direct follow-up to 2012’s Prometheus, Covenant is Ridley Scott’s second prequel to his seminal 1979 original Alien. Unlike its immediate predecessor, which many felt waited too long to feature its signature creature, Scott’s latest delivers the intergalactic monster-movie goods. It’s a fitting and thrilling continuation of the franchise, which has terrified audiences for nearly four decades — and which wouldn’t have survived, much less thrived, without the vital contributions of the late Swiss artist H.R. Giger.

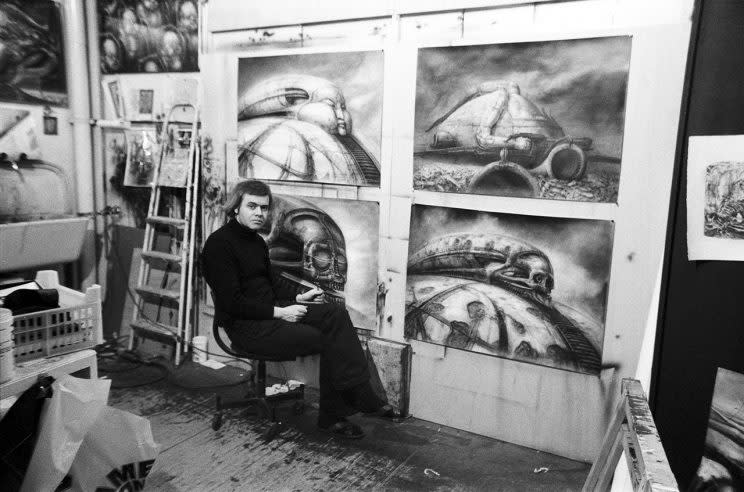

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Giger rose to prominence in Zurich with a series of posters and paintings that intertwined imagery of birth, sex, and death in frightening, entrancing ways. His work melded human and animal figures with technological forms, creating dark, foreboding tableaus that seemed to spring from the black recesses of his subconscious. A surrealist of a distinctly ominous sort — think Hieronymus Bosch or Salvador Dalí as reimagined by Clive Barker — Giger fashioned large-canvas vistas of female bodies, faces, spines, and wombs tangled up in machine-like structures, producing some of the 20th century’s most original and unforgettable sights.

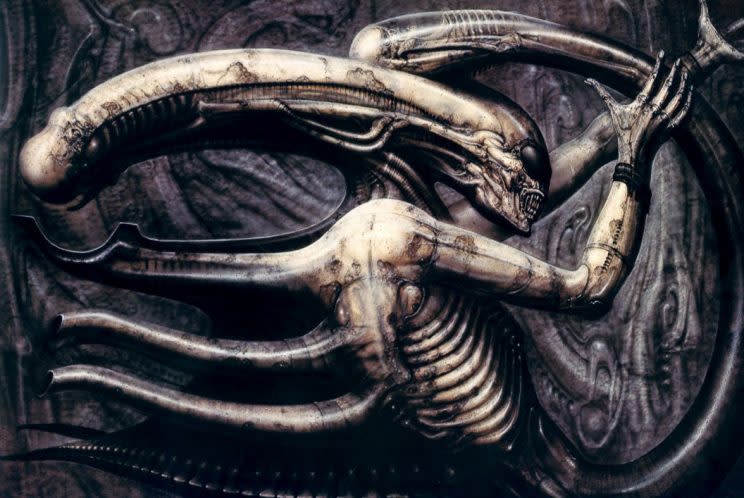

It would be the first compendium of his work, 1977’s Necronomicon, that would forever change Giger’s life and legacy. Courtesy of screenwriter Dan O’Bannon, the book found its way into the hands of director Ridley Scott as he was prepping Alien. Entranced by its images — in particular, Necronomicon IV and V — Scott hired Giger to help craft his horror film’s extraterrestrial beast, as well as the “facehugger” and its eggs, and the interiors of the alien ship. Giger would enthusiastically accomplish those tasks on the set, sculpting and painting his designs himself.

As Scott later wrote in the introduction to H.R. Giger Film Design: “Initially, Giger wanted to design the creature form scratch. However, I was so impressed with his “Necronom IV” and “V” paintings from the “Necronomicon” book, that I insisted he follow their form. I had never been so sure of anything in my life. They were quite specific to what I envisioned for the film, particularly in the unique manner in which they conveyed both horror and beauty.”

Watch a clip of Giger on set:

Giger won a 1980 Best Visual Effects Oscar for his work on Alien. Many behind-the-scenes glimpses of him collaborating with Scott during production can be seen in the supplemental material included on the Alien: Quadrilogy Blu-ray box set, as well as in the 2014 documentary Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World (as well as via the clip above). However, when James Cameron assumed directing duties for the 1986 sequel Aliens, he and 20th Century Fox opted not to enlist the artist’s aid. It was a puzzling (and, frankly, unwise) decision on their part, although Cameron later apologized to the artist via this letter.

Things didn’t go more smoothly on 1992’s Alien 3. Giger was hired by both original director Vincent Ward and his replacement, David Fincher, to concoct new variations of the alien. His updated designs gave the beast a more feral quality (since it’s birthed from the carcass of an animal) and protruding claws from between its fingers, à la Wolverine.

Alas, after initially collaborating with Fincher, the production soon hired Tom Woodruff Jr. and Alec Gillis to head up the creature effects department, and as Giger later opined, “When I’d heard that Woodruff and Gillis have their own version of the Alien, I began to think that they didn’t appreciate mine and that they probably had already sold Fincher on their ideas. But it just seemed my role in the movies never got to the right people. … In the end, they kept some of my ideas, but what is shown in the film is very much changed from my first design.”

At least those involved with Alien 3 spoke to Giger; for Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s 1997 Alien: Resurrection, Giger wasn’t even credited, leading him to write an angry letter to Fox that read, in part: “What would it look like without my Alien life-forms? In all likelihood, all the sequels to ALIEN would not even exist!”

Unsurprisingly, when Scott returned to the franchise in 2012 with Prometheus, the director made sure to bring Giger into the fold, telling Filmophilia (via Slashfilm), “I showed him what we were doing, showed him the story, and he liked it a lot. So he’s doing a little bit of work for me. He’s been doing some murals, big murals, which we’ll see in almost one of the first chambers we encounter when we land where we’re gonna go.”

Scott’s team also went out of their way to pay proper respect to the artist. While the prequel technically took place before Alien (and thus required slightly more primitive variations of its style), creature designer Carlos Huante told io9 that he formulated “a design aesthetic [that] I felt would complement the beautiful Giger style that saturated the first film.” And concept artist Stephen Messing admitted that, as an Easter egg, they even included an “altar” in the “Head Room” that specifically pays homage to his work:

“Another set that I worked on was known as the Head Room. This was a ceremonial room that contained hundreds of ampules beneath a giant sculpture of an Engineer’s head … I also sculpted an altar area for this set that paid homage to Giger — it is a relief sculpture hanging from the wall and has the impression of an alien form with flowing structures surrounding it. There are a lot of Easter eggs in this sculpture — including several hidden Giger motifs that were not used in the original film.”

Giger’s designs would continue to be used in 2004’s AVP: Alien vs. Predator and its 2007 sequel, Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem. The artist died in May 2014 at the age of 74, but his influence is everywhere in the franchise’s latest installment. The artist who conceived some of the most gorgeously nightmarish images to ever grace the big screen, Giger remains one of cinema’s most unique visionaries, and the man who — arguably more than anyone else — is responsible for the monstrous power of the Alien series.

Read more from Yahoo Movies: