James Cameron's '90s 'Spider-Man' Movie: Revisiting the One That Got Away

By Oliver Lyttleton, Yahoo Movies Contributor

Spider-Man swings back into theaters this week in Spider-Man: Homecoming, with Tom Holland as Peter Parker in the character’s first standalone film affiliated with the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The five movies before Holland inherited the costume have taken in more than $4 billion at the box office. It’s a record of success, with more to come — but if James Cameron had had his way, he’d have given Spider-Man fans a movie a decade before Tobey Maguire donned the Spidey suit.

Attempts to bring Marvel’s signature comic-book hero to the big screen go back even further, to the mid-1980s, when Cannon Films’ Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus — responsible for films such as Masters of the Universe starring Dolph Lundgren and Superman IV: The Quest for Peace — optioned the rights to Spider-Man. They developed various screenplays over the next few years, but budgetary issues and Cannon’s deepening financial struggles kept any from ever making it to the starting line. When Golan was pushed out of the company, he took the Spider-Man rights with him, striking a deal in May 1990 with rising studio Carolco, producers of Total Recall and the Rambo movies.

The deal was done, according to Rebecca Keegan’s biography of James Cameron, The Futurist, partly at the director’s behest. Then in the midst of making Terminator 2: Judgment Day for the company, Cameron formally signed on to write and direct a Spider-Man movie after T2 became a huge box-office hit in summer 1991.

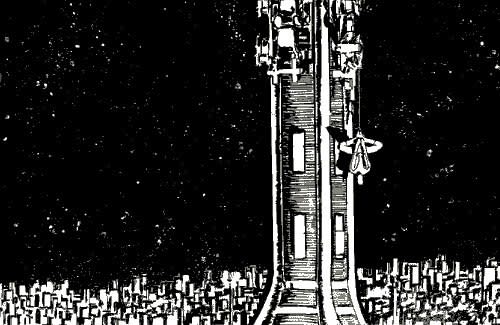

Some time in the next few years, as Cameron was also prepping his Arnold Schwarzenegger-starring actioner True Lies (released in 1994), he also wrote a detailed 57-page scriptment (part script, part treatment, mostly in prose but with occasional snippets of dialogue), which leaked online long ago. The document reveals that Cameron eyed a fairly faithful take on the character’s origins (narrated in flashback by Spidey as he perched on the World Trade Center, also hauntingly the setting of the scriptment’s final action sequence).

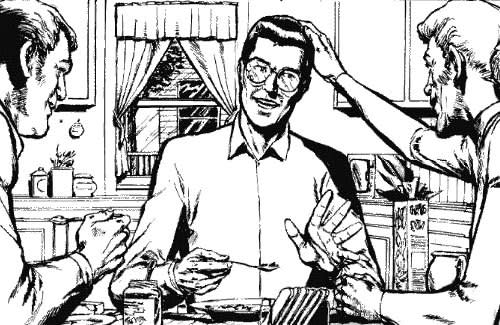

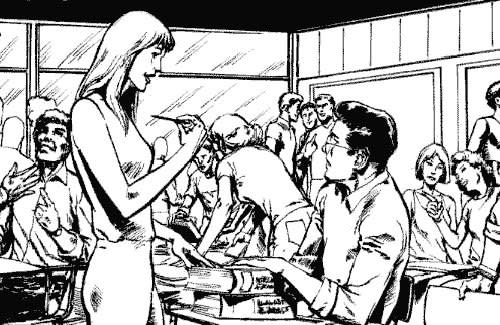

Cameron’s story sees Queens high school student Peter Parker gain amazing powers from being bitten by a spider during a trip to a science lab, feel guilty over the death of his Uncle Ben at the hands of a robber he could have stopped, swoon over popular classmate Mary Jane Watson, become a crime-fighting vigilante known as Spider-Man, and battle supervillain Carlton Strand and his enforcer Boyd (whose powers reflect those of classic Spider-Man bad guys Electro and Sandman, though their origins and names are different here).

The scriptment was approved by, among others, the character’s co-creator Stan Lee, who would tell Keegan: “It was the Spider-Man we all know and love, yet it all somehow seemed fresh and new.” But it’s likely that, had it been filmed, it would have proved controversial among fans. Cameron does a lot right in the document: the action (unsurprisingly for a master of the genre) reads as gripping and inventive, and the sequences where Peter gets his powers, including a dream sequence described in the scriptment as “a David Lynch bio-horror montage of spiderworld,” are more effective than in any screen Spider-Man we’ve seen to date.

But it’s also a strikingly dark and adult take on the character, one where Peter is morally conflicted and even tempted by a life of crime up to the very end. It means that his eventual turn to heroism is truly earned, but it also means a Spider-Man who is often sour and unsympathetic, a bullied kid who becomes a bully, with more in common with the character in the mostly disliked Spider-Man 3 or The Amazing Spider-Man 2 than the high points of the franchise. Cameron’s grown-up take on the character even stretches to cursing — Peter calls Electro a “motherf—er” at one point — and sex, with a strange BDSM lovemaking scene between Spider-Man and Mary Jane on top of the Brooklyn Bridge.

In the end, Cameron didn’t go much further with the project, though he may have offered a villainous role to frequent collaborator Schwarzenegger (“It never got there because he had a battle with the studio and they went in a different direction,” Schwarzenegger would later tell Empire). Menahem Golan sued Carolco when Cameron allegedly tried to take his producer credit off the movie. By the mid ’90s, Carolco was headed for bankruptcy after the expensive flops of Showgirls and Cutthroat Island, which caused a litany of lawsuits over the Spider-Man rights that took in virtually half the companies in Hollywood. Cameron tried to convince his new home, Fox, to pick them up, but the prospect of protracted legal battles deterred them: “For a couple of hundred thousand dollars in legal fees they could have had a $2 billion franchise. They blew it,” Cameron would later say.

Nevertheless, Cameron’s scriptment was initially used as the basis for the movie that finally got going at Columbia in the early 2000s; a number of his elements even made it to the finished film, including the idea that Peter’s web-shooters were organic, rather than a machine he invented. Cameron ultimately decided not to compete for screenplay credit.

There have been a number of other tantalizing what-its for Spider-Man over the years, including a canceled fourth Sam Raimi/Tobey Maguire movie that would have seen the hero battling the Vulture (finally embodied in Homecoming by Michael Keaton), and a Sinister Six villain team-up movie from Cabin in the Woods director Drew Goddard that was scrapped after The Amazing Spider-Man 2 underperformed. But we’ll always be most intrigued by what Cameron’s version would have looked like, whatever the flaws in the story. At least for Cameron, he rebounded when it didn’t happen: The films he did make — Titanic and Avatar — are the two top-grossing movies in history.

Spider-Man: Homecoming: Tom Holland Answers Yahoo Movies’ 15 Questions:

Read more from Yahoo Movies: