'Longtime Companion' Is 25: An Oral History of the Trailblazing, Heartbreaking First Major Movie About AIDS

Bruce Davison and Dermot Mulroney in ‘Longtime Companion’ (Everett)

In the summer of 1990, the AIDS crisis in the United States was almost a decade old. By the end of that year, the disease would claim over 120,000 lives to date in the United States alone. Though AIDS had begun as an obscure and seemingly isolated medical crisis — one that had been introduced to most of the country via a 1981 New York Times story featuring an ominous, now infamous headline, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” — it had exploded into a terrifying epidemic with no end in sight.

For the first few years at least, one of the hardest hit communities was gay men in cities like San Francisco and New York. “It was so unreal seeming,” says playwright and screenwriter Craig Lucas, who lost many friends to the epidemic. “It would be like suddenly all the brown-haired people in your world were getting an autoimmune disease that was crippling and killing them in a matter of weeks. It just didn’t make any sense.” AIDS cut a devastating swath through creative professions in theater, dance, and film, but aside from the 1985 TV movie An Early Frost and the little-seen 1986 film Parting Glances, there had been no other film dramatizations about what it was like in those years. It was a stunned, benumbed kind of silence that desperately needed breaking.

In May of 1990, Lucas and director Norman René set about doing just that with the premiere of their debut feature Longtime Companion. With a deceptive simplicity, the movie unspools like a newsreel, telling the story of a group of gay friends in New York City from 1981 to 1988, as their panic rises and their numbers dwindle. It was the first movie about AIDS to get a wide release and major media attention, and it earned costar Bruce Davison a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Critic Roger Ebert praised the movie, saying it contained, “one of the most emotionally affecting scenes in any film on dying.”

More than a quarter century later, Longtime Companion remains both an essential film in the history of the epidemic and an enduring portrait of grief and loss. Yet in recent years, Longtime Companion has fallen into an undeserved obscurity: It’s currently not available on streaming platforms, and the DVD is out of print. So on the 25th anniversary of its release in theaters, we wanted to look back on the film and talk to the cast and crew about their remembrances of making one of the earliest movies about life in the plague years.

PART I: “I didn’t realize how hard it would be.”

In the late-1980s, stage director Norman René and playwright Craig Lucas — both gay men living in New York — were a creative team on the rise. They’d had success with their plays Blue Window (1984) and Reckless (1988), and were only a few years away from opening their acclaimed Prelude to a Kiss on Broadway in 1990.

Inevitably, the movie studios came calling. Lucas’s first idea, though, wasn’t a popular one: He wanted to make a movie about gay men and the AIDS crisis. The duo also pitched executive Lindsay Law, then head of the PBS anthology series American Playhouse, which produced theatrical as well as TV movies.

Lindsay Law (executive producer, Longtime Companion): “We’d done a [TV] movie version of Craig’s play Blue Window, which is how I’d met both of them…. It got some notice, and suddenly they were able to have those kinds of meetings. [But] if they brought up a gay storyline, that did indeed shut down the whole conversation.”

Craig Lucas (screenwriter, Longtime Companion): I was invited by a number of film producers to meet about possible projects. They all said more or less the same thing: “What would you like to write about?” I would say, “Something about the community out on Fire Island as it was hit by the AIDS epidemic.” And they would always respond with something like, “Oh wow, great. But after that, what would you like to write?”

When I suggested somebody make this movie about the first years of the epidemic, I didn’t realize how hard it would be. I just assumed there would be real interest. I was na?ve about how rampant and deep the homophobia ran.

Law: I do remember the New York Times making the note that the visual media was completely ignoring this terrible event that was going on across America. It’s not like today, when you watch television, and whatever’s on our minds is repeated on every sitcom. I thought, “Well, we’re one of the few organizations who can decide, ‘Hey we should do this.‘” So I commissioned two different pieces, one of which was Longtime Companion.

Mark Lamos, Campbell Scott, Dermot Mulroney, and Bruce Davison

Lucas got to work on the script for the film, drawing in part from his own memories about the epidemic’s early days — including that New York Times article announcing the “gay cancer” that would later be known as AIDS. Lucas opened his script on July 3, 1981, with all the characters reading the piece.

Lucas: Within days [of that article running], a very close friend had gotten sick and died within 36 hours. And then, within a couple of weeks, I was on the subway and I started seeing friends with [Kaposi’s sarcoma] lesions. The cloud of it was moving so rapidly that suddenly, I knew three dozen people who were sick or dead. By the time I started working on the screenplay, I knew 99 people.

Mark Lamos (actor, Sean): You suspected it about everybody. You thought, “Well, is he gaining a little weight because he’s on some kind of drugs? Or is he losing weight because he wants to be thinner?” You just didn’t know. And you couldn’t say, “Hey are you feeling OK, are you sick, do you have it?” You couldn’t do that.

Debra Kletter (assistant and friend of Norman René): You could not help having this black hole of fear in the corner of your heart and mind all of the time. And my biggest fear was that something would happen to Norman.

Anthony Jannelli (cinematographer): You would open the New York Times every single day and see on the obituary page a story about a young person dying at age 32 or 40, and the very last line would always be the same: Survived by his longtime companion.

Lucas: I couldn’t get any momentum or a foothold [on the screenplay]. Norman said, “What if…you pick one day a year for the nine years of the epidemic so far and simply show how each of the characters gets through that particular day?”

We wanted to make it almost as if it were a documentary.

Lucas stuck to that structure, with his final script focusing on a community of gay men who lived in Manhattan, summered in Fire Island, and were devastated by the first waves of the disease. Among the movie’s circle of friends: wealthy couple David and Sean; Willy, a quiet gym trainer from the Midwest, and his best friend, John; Fuzzy, a lawyer, and his childhood friend Lisa; and a young, fashionable couple named Michael and Bob. Meanwhile, a parallel story takes place featuring another longtime couple in New York City: Howard, a soap opera actor and Paul, a business exec.

With a $1.5 million budget from American Playhouse — Law had been unable to find any additional financing — Lucas and his producers set out to cast the film.

Stan Wlodkowski (producer): We wanted some marquee-type names simply because we knew the film would get a wider release. We knew we were doing something that could have some resonance.

Lucas: We offered it to all sorts of name actors…but the only name to agree to be in the movie was Alec Baldwin, and then he had to drop out because of a scheduling conflict.

Wlodkowski: I frankly don’t want to say [the] names [of the actors who were approached]. It might imply they didn’t want to play a gay character, or that they didn’t want to appear in something about HIV. But the truth is: Who knows? They might not have liked the script or the role. But we did struggle to get the cast together.

Lucas: One of the people who did the movie had a big, successful agent who said, “Don’t do it — you do not want to make your name playing a gay character.” And this actor said, “That’s ridiculous. I’ve grown up around gay people, and I’m going to do this movie.”

Eventually, Lucas and his producers settled on a cast that drew largely from the New York theater world — including Mark Lamos, Mary-Louise Parker, and Campbell Scott — as well as screen stars like Bruce Davison and Dermot Mulroney. “It was the only movie I’ve ever done without having read the script,” remembers Parker, who knew Lucas and René after starring in an early version of Prelude to a Kiss and who took the Companion role of Fuzzy’s confidant, Lisa. “I just said, ‘I’ll play whatever you want me to play.’”

For Lucas though, there was one notable name missing from the cast: Peter Evans, a respected stage actor and a close friend of Lucas’s. “I wrote the role of Sean for Peter,” Lucas wrote in an email. “[But] he became extremely ill in 1988 and 1989 — frequently hospitalized, losing weight, his consciousness sometimes affected.” Evans initially thought he could handle a smaller role in the movie, but then became too sick for even that. Lucas missed part of the film’s production to be with Evans in Los Angeles just before he died in May of 1989 at age 38.

Stephen Caffrey, Campbell Scott, and Dermot Mulroney in ‘Longtime Companion’ (Everett)

PART II: “These were just people dealing with extraordinary circumstances.”

With a small budget, a quick 36-day shooting schedule, and a first-time feature film director in René, the production faced its own set of challenges. Longtime Companion was set almost entirely in New York City, except for a few sequences in the Pines on Fire Island, an exclusive gay beach town that had been hit particularly hard by the epidemic. The Pines is only accessible by ferry, so the cast and crew moved out there in May 1989 — right before the summer season started — to shoot the early, idyllic sections of the film.

Lucas: At first, the property association said, “No, you cannot film your movie in the Pines.” I called them up and said, “So I’m going to call the New York Times, and I’m just going to tell them you guys — every last one of you is gay — do not want to be associated, in 1989, with a disease. So what do you want to do about that?” And they said, “OK, make your movie here.”

Wlodkowski: Normally in May, you get two or two inches of rain on Long Island. That May, it rained 10 inches.

Lamos: It was awful watching that very first scene in the picture, where Campbell Scott [strips naked and] goes running into the water. If you’d just pulled back, you would’ve seen the entire crew in these parkas and hoods.

Campbell Scott (actor, Willy): The water was very cold. I was not acting. But that was perfect — it kind of sends the movie off with this [feeling of], “Oh, this is how wonderful and freeing it all was for a little while.”

Dermot Mulroney (actor, John): We all shacked up together in rental cottages. I was a 23-year-old straight kid, having my body makeup applied for this scene where I’m in the Speedo bathing suit. Freezing cold morning, wet sponges.

Jannelli: In retrospect, when I watch the film now, I think some of those foggy beach scenes are actually better because they seem so mysterious and almost heavenlike.

Bruce Davison (actor, David): When we were shooting in Fire Island, Joe [Dal Corso, the hair stylist] was crying on the front porch. I said “What’s going on?” and he said, “You see that house over there? I used to have a share there with nine guys, and I’m the only one left. I figure I’ve got about six months left.” And he was right. [Dal Corso died in 1990.]

If Longtime Companion was one of the early movies to dramatize AIDS, it was also the rare film to present gay men as normal, unremarkable people — all of them living, as Lucas described it “rather quotidian middle-class lives.” That’s why it was perhaps ironic that a lot of the men in the cast were actually straight.

John Dossett (actor, Paul): One of the reasons this movie was so great was that there weren’t any stereotypes. You think of [movies like] Boys in the Band, and you see every caricature up there. These were just people dealing with extraordinary circumstances.

Brian Cousins (actor, Bob): [Dermot] was adamant about buying in, and having fun buying in — don’t be self-conscious because we’re these straight guys playing gay men. Let’s enjoy the fact that we get to share this part of ourselves now.

Mulroney: I went out and bought deck shoes, and I also went to a bookstore and got a book that was entitled How to Be a Male Model. That’s how I prepared. [I saw John] as an aspiring model who never got his shot.

Cousins: Michael Schoeffling [who played Michael, and was best known as the dreamboat Jake Ryan in Sixteen Candles] and I were going to be lovers in the movie, and it just hit us in the face. I think that was something he and I might’ve even said to each other: “For this to work, I’m going to love you like you’re my partner. If you want to grab my hand, please grab my hand. If I’m kissing you, I’m kissing you.”

Ira Sachs (assistant to the director): So much of the movie is about the communal family that these men and a few women created together. So many gay men came from places where they had to hide, and suddenly they were in a place where they could be surrounded by people who accepted them. New York was a profound place for gay men.

After the carefree scenes on Fire Island, the movie takes a sudden turn, as Mulroney’s character, John, falls ill with pneumonia and lands in an overworked New York hospital. The movie takes an almost clinical view of John’s illness: We see Willy (Campbell Scott) and David (Bruce Davison) trying to convince him (and each other) that it can’t possibly be as bad as they fear. But John’s death comes quickly, and happens offscreen. The last image of him is an overhead shot in a darkened hospital room, struggling to breathe and looking dreadfully alone.

Jannelli: [John]’s got a million tubes hooked up to his body and a respirator, and the beeping of the medical equipment, and the camera is kind of revolving around him. He’s just lying there with his eyes open, thinking, “What is happening to me?”

Lucas: The shot of him alone in that ICU from above — when he’s left in his room at the end, and he’s just staring up, hooked up to all those machines — is to me the heart of that movie. It’s so terribly, terribly sad.

Watch the hospital scene:

Mulroney: The thing that I had to do in that shot was time out my chest heaving up and down [with] the machine that was running next to me. But I also remember not being able to not cry.

Law: To go from seeing people that you know or recognize, and then to watch them, one by one, disappear in the way that they do. You couldn’t possibly live through a movie that had that many deaths. So people literally, with no comment whatsoever, suddenly disappear from the storyline.

René’s and Lucas’s response to all this overwhelming sadness was to keep stripping away overly dramatic moments. One of the striking things about Longtime Companion is how funny it actually is, and how often those moments — from Fuzzy lip-synching the Dreamgirls theme to Lisa and Willy discovering a glamorous beaded gown in Sean’s closet — come immediately before or immediately after some of the film’s darkest scenes.

Lucas: Norman felt very strongly that when people are under duress, they survive by laughing and seeing the absurdity in the situation they’re in.

Kletter: You do get to the horror of it on a mass level, but the story is told through people’s personal realities. And life is funny — at its darkest moments, there’s great humor.

Lucas: [Norman] didn’t want this movie to be an art object. He wanted it to look like a documentary crew had shown up at the hospital and was shooting off the cuff…. It was the same thing with the music: There were composers who wanted the [composing] job, [and they] wrote beautiful, lush, heartbreaking music. And Norman was like, “No, that’s not what people are listening to when they find out they have HIV. They’re listening to Madonna. They’re listening to Blondie. They’re listening to crappy, catchy pop.”

The film’s most famous scene — and the moment that surely got Davison his Oscar nomination — was also a study in restraint. As the years pass onscreen, Sean (Lamos) gets horrifically ill and is nursed by David (Davison), who’s presumably HIV positive but still healthy. Toward the end, as a delirious and emaciated Sean is moaning from his bed in their apartment, David takes his hand, and quietly and persistently tells his partner that it’s all right for him to die. “It’s OK,” he says, repeating over and over, “Let go.”

Watch the scene:

Davison: When we were ready to shoot, Norman gave the best advice to both of us. First of all, he said to my costar, “You’ve lost the weight, Mark. You’ve done everything you can. I want you to just do what he tells you to do. Listen to him. Do what he tells you to do.” And he said to me, “This isn’t about how you feel. Get him to let go.” Action.

Lucas: Every syllable of that is scripted, and Bruce learned it with great specificity and conscientiousness — the ellipses and dashes and “you knows” and “uh-huhs.”

Kletter: Bruce, of course, wanted to make it much bigger…. And Norman really had to work with him on that, to keep bending it back and explaining why this was so much smaller than that.

Lamos: There was a point when Norman was overcome with tears. It wasn’t an emotional thing he was directing — [it was] some really boring technical thing — and all of a sudden, his eyes filled with tears. He said, “Excuse me,” and he left the room and everything stopped. And there was this kind of black hole. I was so concentrated on where I had to be, I only registered that peripherally. But then when I heard Norman was ill afterwards, that moment came back to me.

Norman René had kept a secret from almost everyone on the production: He’d found out he was HIV positive shortly before the shoot began. Part of his silence was purely practical. No insurance company would have covered him for the shoot had his diagnosis been known. Lucas’s partner, surgeon and AIDS educator Tim Melester — who himself was HIV positive, and who died in 1995 — falsified René’s paperwork so he would pass the insurance requirements.

Kletter: When he went to get the test — because it just seemed like the right thing to do — he was shocked. He didn’t expect to be positive. I remember walking home from the test with him. We were just kind of like, “OK, so we’ll figure out how to deal with it.”

Lucas: Norm was pretty healthy at that point, though he did occasionally have lesions on his arms or neck and had to cover those. That was stressful for him.

Law: They knew not to tell me, because of course you have to get insurance on movies. I was the last person they told, because then the project might not have happen.

Lucas: I was just so angry that he was sick, while Tim [Melester] was also sick, and Pete [Evans] was sick. Another one of the actors, who had a large role that ended up getting cut significantly, was also sick. [Brad O'Hare, who played a waiter in the film, died in 1994.] We were together every day, and we were taking our experience and putting it into the film and trying not to be hysterics. But it took a great deal of concentration and focus to not be in a persistent panic.

Campbell Scott and Dermot Mulroney in the final scene

Lucas and René devised an ending for Longtime Companion that seemed a direct response to all the death around them. In the final scene, three of the surviving friends, Willy, Fuzzy, and Lisa, are walking on an empty beach. Their conversation turns to — what was in 1988, at least — an impossible future. “I just want to be there. If they ever do find a cure,” Willy says.

Then, as if his wish were granted, crowds of people — including a radiant Sean, David, and John — stream down the boardwalk cheering and celebrating, as the mournful guitar song “Post Mortem Bar” by Zane Campbell plays on the soundtrack. It’s a magical vision of an end to a war, and it disappears almost as suddenly as it began, leaving the three alone on the beach again.

Mulroney: The movie’s poster shot came from [that scene.] I didn’t know going in that I’d wind up literally being the poster boy for AIDS stories. But it’s a position that I long cherished.

One of the movie’s posters

Law: The only thing that I felt about the ending was that we didn’t have enough money to do what Craig really wrote. It’s fairly paltry. It should’ve been tons of people pouring down that boardwalk.

Parker: I can’t even really watch that scene now. It was so emotional, it almost risked being called sentimental or something like that. Sentimental sometimes has a negative connotation, but it is in the best way — in the poetic way.

Lucas: It was controversial. I remember a friend of mine, a wonderful playwright, saying, “You know the dead aren’t coming back! They’re not coming back, godammit! Why are you giving us that happy, sentimental ending?” I said, “I don’t think it’s happy at all.”

Zane Campbell (singer-songwriter): I ended up writing that song thinking, “You know, I still like the idea of it being an afterlife bar, where when you die and go to heaven, you sit down and wait for your friends to show up and tell their stories.”

Watch the final scene:

PART III: “We’ve got to invite everybody who has a mouth.”

Longtime Companion had as difficult a time finding a distributor as it did getting financing. Law, for one, had expected that since the film was already getting good responses at early screenings, finding a distribution company would be relatively easy. But while there were a lot of compliments, there was no contract. “They all said, 'I know you’ll find a distributor. It’s a really good film — it just doesn’t seem like a good fit here,’” he says. “I don’t think they were necessarily euphemisms, but maybe they were.”

The team waited months to hear some news. Just before it was to screen at the Sundance Film Festival in January 1990, Longtime Companion finally got some interest from the Samuel Goldwyn Company, which was run by future Sony Pictures chairman Tom Rothman. At the time, Rothman was quoted as saying the movie would be a “harder sell than Shakespeare,” but “whatever happens, I can say right now that I’m glad we were willing to take that chance.”

Law: [We scheduled] a buzz screening in New York, where we said, “OK, we’ve got to invite everybody who has a mouth: well-known hairdressers, people in the media, people on news bureaus, and lots of gay people who are in positions of power.” Just to get them talking about it, hoping that they could pry loose something. And I introduced it by basically saying, “Listen if you like this, don’t keep it to yourself.”

Wlodkowski: Tom Rothman and the Samuel Goldwyn Company were the ones that stepped up. They didn’t pay a lot of the money, but they guaranteed a certain size release, which was very important to Norman and Craig.

Law: I think literally two weeks later, we were at Sundance.

Wlodkowski: Norman was not able to attend the festival because he was directing a play on Broadway, so Craig and I went. The Audience Award comes up… So we kind of looked at each other like, “If we win, who’s going to go up?” And then we did win, and I said, “Craig, you should,” and he said, “No, no, no, you go.” So I went, and I stood there like a deer in the headlights.

The movie opened in May of 1990, providing an overwhelming catharsis to audiences who hadn’t yet seen this kind of story on the big screen. Most of the reviews were positive, while a few were outright pans. (In the New York Times, critic Vincent Canby slammed it for being “self-absorbed” and “insipid.”) The movie also faced intense criticism from activists in the LGBT community like Sarah Schulman and Michelangelo Signorile, who called out its lack of political fire and its almost exclusive focus on middle-to-upper-class white men.

Kletter: Norman would get [questions like]: “How do you address the question of there not being more minorities and it not being more political?” And Norman kept saying, “I made the movie about AIDS I wanted to make. You are free to make the movie you want to make.”

Sarah Schulman (novelist, playwright, and activist): In 1990, I had been at ACT UP [the influential AIDS activist group] for three years. And every single day, I was working and living inside a very broad coalition of people with AIDS. So it was jarring to walk into a theater and see a representation that was so one-dimensional. And to me, I think there was something that felt false about it.

Lucas: From her experience, it didn’t show what Sarah was seeing on a daily basis [in downtown New York City], and I understand that. It’s just an odd expectation, and it does come from the lack of dramatic representation in film.

Kletter: At the premiere at the Ziegfeld in New York, I was sitting next to Norman and Craig. I don’t know that they had any idea what they created or just how powerful it would be. And everyone started cheering and applauding, and I looked at them and I said, “You have to stand up.” And they were both like, “What?” They stood up and people rose to their feet, and it was just, the whole Ziegfeld Theater, just cheering and screaming and crying.

Wlodkowski: I was on location for something else in Florida when the movie opened, and I do remember going to the movies one night. I opened the door to the auditorium and I looked up at the theater and it was sold out. I must’ve walked in when it was an emotional scene. You could hear the Kleenex coming out and people sniffling.

Bruce Davison accepting his Golden Globe in 1991 (DCP)

Longtime Companion grossed $4.6 million and was considered a modest success for an indie movie. “Bruce was nominated for an Oscar — nowadays little movies get nominated all the time, but back then, it really was kind of unusual,” says Wlodkowski. Any first-time director would have been thrilled, but for Norman René, time was already running short. He and Lucas would go on to work on the film adaptation of Prelude to a Kiss (1992) and a movie version of their play Reckless (1995). René and his partner Kevin McKenna would even live in Italy for a time.

But by 1996, René’s health was steadily failing. Just before he checked into the hospital for the last time, he insisted on going to Atlantic City to play blackjack. “He said, 'If you don’t come with me, I’m going to go by myself,’” Kletter says. “He called for the results of his latest test from a payphone in the lobby of the casino.” He died on May 24, 1996 in New York, at the age of 45. Kletter still wonders what might have happened if he had lived to get the drug cocktail that would become the closest thing to the cure Willy so desperately wanted to see. “If he could’ve just hung on for another year or so, maybe it would’ve been different,” she says.

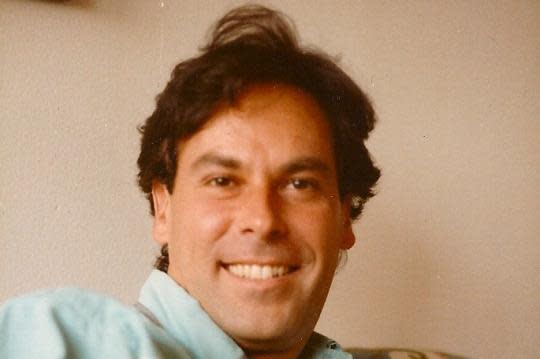

Norman René in an undated photo

Kletter: For his memorial service, we found a dilapidated old barge at the end of Red Hook in Brooklyn. We had a strolling concertina player, and big Italian garden string lights hung everywhere…. At the end of New York City, looking off to the Statue of Liberty … it was just filled with people that loved him. People got very lost going there — one car never got there. We felt like that was the process. It was very much like Norman: “You’ll figure it out.”

Wlodkowski: Norman had one of the wickedest, cleverest, wittiest senses of humor of anyone I’d ever met. He could just brighten the room when he walked in. He had this long flowing mane of hair, and he just was this striking, charismatic person.

Scott: Once you had a conversation with him, you thought all of the ideas were your own and that he had said very little — when in fact, he’d probably said something very precise and very specific.

Mulroney: He was beautiful. I miss him sometimes. He’ll just come into my mind when I’m acting on something, so he’s still around.

Lucas: Norman used to say, “You make a little bargain. You say 'OK, I can get through anything as long as I don’t lose my eyesight.’ Then it’s like, 'OK I’ve lost my eyesight, but I can still get through it as long as I can still walk.’ Well, now I can’t walk.” You just keep making new bargains. People’s resilience is extraordinary.

Kletter: Many years before, a friend had sent him to some spiritual-awakening workshop for a week…. You had to do exercises about where you see yourself in one year, five years, 10 years. Norman made all these lists, and the thing that I said at his memorial is that he did everything on his list. He wanted to live in another country, he wanted to have a relationship, he wanted to direct a Broadway show, he wanted to direct movies, he wanted to have a dog. He didn’t know he was going to do all of those things then. But he did.

Wlodkowski: I counted once in my address book — and then I threw it out because it was so depressing — that there were 22 people that I had crossed out who had died. To some extent making [Longtime Companion] was kind of almost healing, a way to address all the pain and all that loss.

Sachs: What’s interesting to me is the disappearance of the film. I feel like it hasn’t been canonized in a way that I would like it to be. It is a really accurate depiction of a time and a group of people and a crisis.

Kletter: People that I meet who know that I have any connection to the movie, even now, always talk about that [final] scene. Just the camera panning around, and you spotting people who had died waving and smiling and laughing and talking. It kills me, because I just wish it were true.